Thursday, 10:00am

17 May 2018

Enigmas of abstraction

Photography records with startling accuracy. Why use it to create non-representational images? Photo Critique by Rick Poynor

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor, written exclusively for Eyemagazine.com

Abstraction might seem like a marginal issue in photography. Here is a medium capable of recording the world in front of the camera with startling levels of visual accuracy. Why use it to create non-representational shapes and compositions? Large aesthetic and intellectual claims were made for abstract painting in the course of the twentieth century, peaking with abstract expressionism in the 1950s, but abstraction ceased to be a primary concern for artists and art critics a long time ago. Is photographic abstraction anything more than a mildly diverting imitation of an approach to painting that turned out not to be the way forward for visual art, after all?

Tate Modern’s ‘Shape of Light’ aims to present the key moments and intersections from ‘100 years of photography and abstract art’. That summary appears to put abstract art in the ascendant as the reference point against which efforts at photographic abstraction must be measured and assessed. The show begins a little unpromisingly with meticulously fabricated photographic genuflections to Wassily Kandinsky by Marta Hoepffner, such as Homage to Kandinsky (1937) made a decade after the painter’s Swinging, which is on show beside them.

Marta Hoepffner, Homage to Kandinsky, 1937. Stadtmuseum Hofheim am Taunus. © Estate Marta Hoepffner.

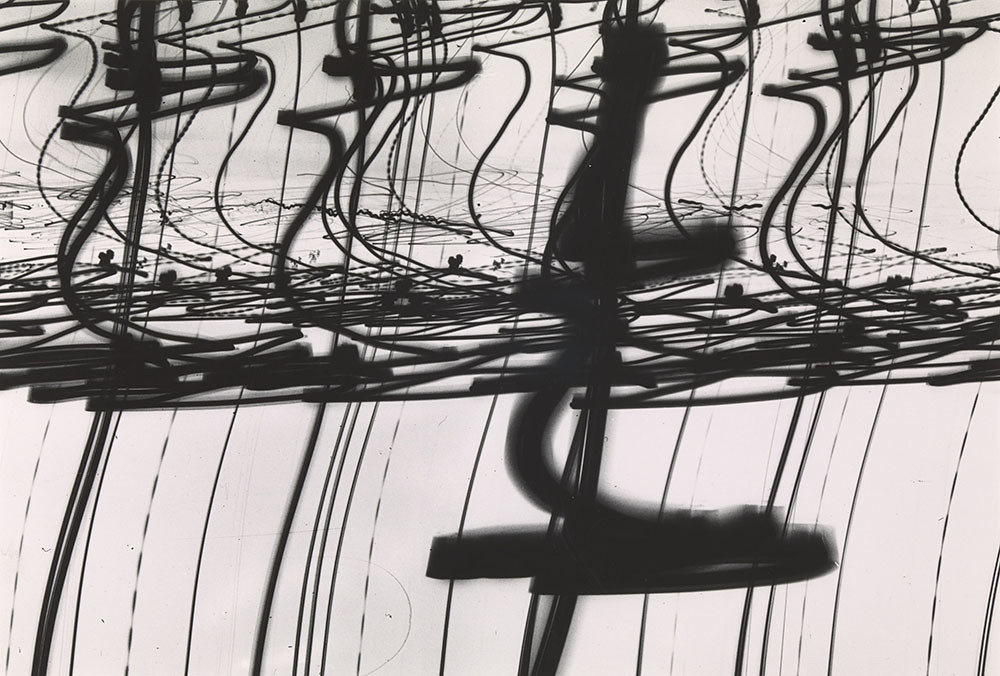

Top: Otto Steinert, Luminogram II, 1952. Jack Kirkland Collection Nottingham. © Estate Otto Steinert, Museum Folkwang, Essen.

Pierre Dubreuil’s Interpretation Picasso: The Railway (ca. 1911) also alludes respectfully to its inspiration – here Cubism – in its title. This little-known picture, like light suffusing dancing planes of crystal, is the earliest example of photographic abstraction in the show. It is a fascinating experiment, yet still takes its cue and purpose from fine art.

Pierre Dubreuil, Interpretation Picasso: The Railway, ca. 1911. Centre Pompidou, Paris Musée national d’art moderne-Centre de création industrielle.

As the exhibition unfolds, photography feels less in thrall to painting. A single art work features in each of the themed rooms – Joan Miró (in ‘Finding Form’), Jackson Pollock (‘Drawing with Light’), Jacques Villeglé (‘Surface and Texture’) – supplying a contextual anchor. By this time, though, in the middle of the century, photographers are confidently investigating lines of inquiry rooted in the nature and possibilities of photographic practice. While there is a superficial similarity of form between Pollock’s wild tangles of dripped paint and Light Tapestry (1939) by Nathan Lerner or Luminogram (1952) by Otto Steinert, the photographers’ concentration on pure effects of light engages with the very essence of their medium. It is striking, too, how modern these technological realms of illumination and evanescence still look compared to Pollock’s earthy, surface-bound, gestural mark-making.

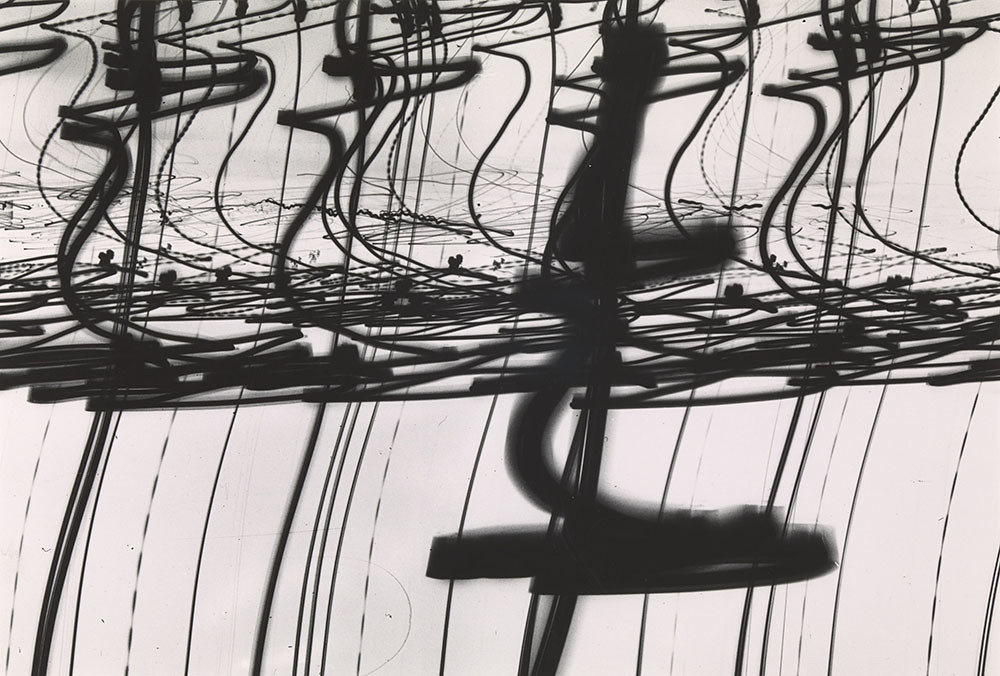

Installation view of ‘Shape of Light’ with Number 23, 1948, by Jackson Pollock (left). Photo: © Tate (Seraphina Neville).

The photograph isolates a section of the world to appropriate it as a picture and this means it has an inherent capacity to produce abstraction. The tighter the focus, the more ‘abstract’ (though it remains an object) the material remaining within the frame can become. Aaron Siskind spoke of the photograph’s ability to ‘transform a realistic scene into abstraction’ and his picture Jerome 2 (1949) accomplishes the task with leaves of paint flaking off a dried-out wooden surface, most likely outdoors. The curling fragments have an incredible lacquered density. The chaos of a corner of the world is transmogrified and reordered as an image.

In an even more enigmatic untitled picture from 1952, Guy Bourdin – later renowned for fetishistic fashion photos – singles out a triangular grid of holes in an unidentifiable metal sheet, the dark apertures randomly connected by a network of cracks. It would be possible to paint an image like this, but the found sheet’s brute reality and now unfathomable purpose give it a greater sense of portent. The photograph represents an abstractionist mode of perception without actually being an abstract. In the words of curator Simon Baker in the excellent catalogue, pictures like this become ‘fully autonomous, complete and self-contained new objects’.

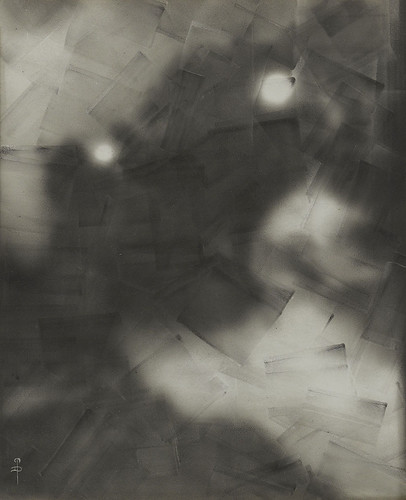

The middle rooms dealing with the 1930s to 1960s are the most compelling. These photographs retain the feeling, even now, of being discoveries. They have the autonomy that Baker identifies, they achieve a conceptual, technical and aesthetic balance, and they represent once new ways of seeing. Their freshness is confirmed with a restaging – one of ‘Shape of Light’s highlights – of parts of ‘The Sense of Abstraction’ photo-exhibition held at the Museum of Modern Art in 1960. This includes seven Unconcerned Photographs (1959) by Man Ray, who swung a Polaroid camera around dismissively when asked for pictures by MoMA (at Tate Modern one of the enlargements appears to be displayed upside down).

Man Ray, Unconcerned Photograph, 1959. Museum of Modern Art, New York. © Man Ray Trust / ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2018.

In the last room, ‘Contemporary Abstraction’, Maya Rochat, whose quasi-psychedelic lava flows cover the final wall, poses an unavoidable question: ‘How can you make an impact with images when everyone sees so many?’ Rochat wants her pictures ‘to be images for today’. As with plenty of contemporary art, that quality of now-ness seems to be more about scale, use of new media and hybridising processes than about innovations in visual content.

Maya Rochat, A Rock is a River (META RIVER), 2017. Courtesy Lily Robert. © Maya Rochat.

Although artists are still making abstract photographs, they feel less pressing today, like wordy post-digital footnotes to history. In 1992, Sigmar Polke put chunks of uranium on photosensitive paper to generate random green blurs; they gain by being seen as an edited group. Alison Rossiter creates camera-less photos – glowing blocks of nothingness – by developing expired photographic paper from the 1930s. Thomas Ruff attempts to break the world record (in his own phrase) by devising giant photograms in a ‘digital darkroom environment’. Despite their vast size, they are easily eclipsed by Moholy-Nagy’s and Man Ray’s ethereal pioneering photograms, shown in earlier rooms. This is an impressive, in many ways unmissable show that ends up suggesting, in spite of itself, that photographic abstraction ran its course some time ago.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, Professor of Design and Visual Culture, University of Reading

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.