Winter 1991

Eurothis and eurothat

Will the political and monetary union of Europe lead to an increasingly homogeneous graphic design? Or will designers fight for solutions that are local to a country’s culture yet international is resonance?

‘Eurothis and Eurothat’ – a half-Scottish, half-Finnish friend said to me. Euroculture may at times seem pervasive, she implied, but it needs to be questioned. Yes, certainly we live in a world in which it is becoming increasingly difficult to know where people come from. In graphic design over the last ten or 15 years, the headlines have been grabbed by a strange brew of punk-Swiss, wild-Dutch and freaked-out-Californian, with smatterings of London street culture. This stuff is sometimes given the name of ‘post-modernism’ and is then propped up by the doubtful theories of post-structuralism. Confused and obscure in its visual forms and its thoughts (the two go together), this design work is terminal. But then, as the theory proclaims, everything is all only surface, especially when seen in reproduction.

And yet, especially since the political revolutions of the last two years, we also live in a world of resurgent nationalism, and of an astonishing assertion of national identities. Fifteen years ago, one hardly bothered to distinguish ‘Scottish’ from ‘English’, or ‘Catalan’ from ‘Spanish’, and many people thought that ‘Russian’ and ‘Soviet’ were synonymous. But now such distinctions have become vital, the notion of Euroculture seems less simple.

As well as its material substances, graphic design is made of verbal and visual languages. Texts cannot escape the fate of existing in a particular language. Less obviously, images also carry with them culturally specific meanings. For example, with graphics from the old Eastern-Bloc countries, those of us outside that particular culture always found it a struggle to grasp the oblique expression that state repression encouraged. On the other hand, consider the complex visual codings that have recently been given to corporations in Britain, especially those taken out of state control (telecommunications, electricity, gas, water, and more). For some of us within the culture, the new identities seemed to be couched in a language of slimy and poisonous ingratiation; for those outside, these images must be as harmless as they are visually bland.

The argument that I want to make has to take in various other factors, as well as those of the specificity of verbal and visual languages. Graphic design is done for particular clients, who may be a transnational company or the local ironmonger. Either way, there are good clients and not-so-good ones, broad-minded and narrow, Euro and not-so-Euro. As for the designers themselves: all of these considerations of attitude and culture form part of what the designer brings to a job. Even a simple bag for an ironmonger will be the outcome of a complex set of factors. Among them one might cite the magazines that a designer reads (or leafs through).

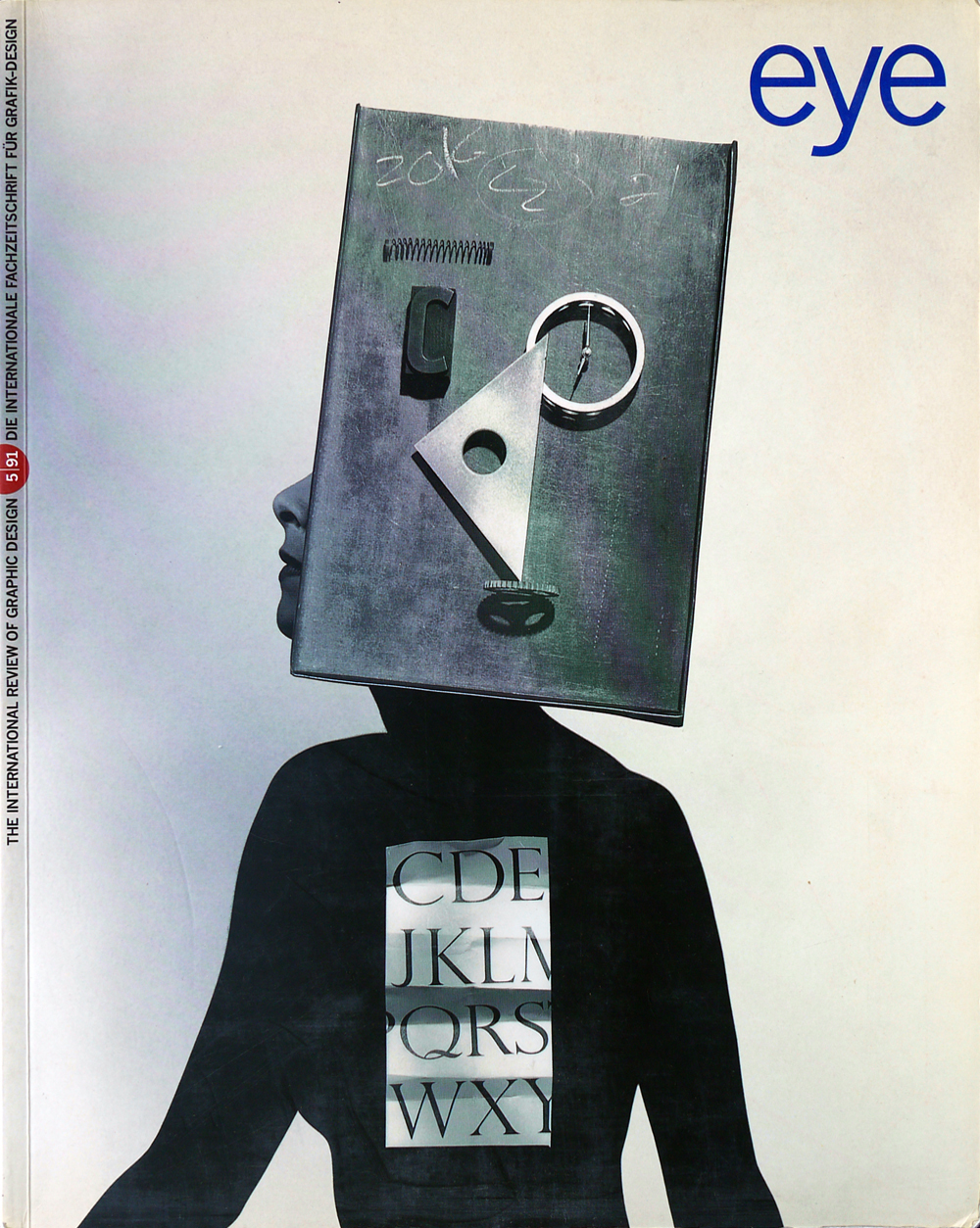

Magazines play a notoriously important role in architecture: if buildings can’t move, images of them can and do. In this way, ideas are adapted, translated and transplanted; reputations are established and spread. The same process works in graphic design, though with more complications because graphic design is made in multiple copies which can usually be moved around, and the magazines that sometimes reproduce these copies are themselves graphic design. Nevertheless, compared to architecture, graphics has a less developed culture of publication. This might be an advantage, but it also means that graphic design suffers a grave lack of critical discussion.

Returning to the ironmonger’s bag, the factors which impinge on its design come from two directions: those specific to the local culture and those reaching out for some wider reference. This complexity of viewpoint is what has been disastrously lacking in ‘heritage culture’: a version of the past that, while using the latest transnational technology, pretends to be a merely national and backward-looking reference. It ends up making the local and specific feel like nowhere and nothing. The recent interest in a graphic design ‘vernacular’ may be another symptom of the times, and has thrown up interesting results, but it seems to embrace a false primitivism: designers with a working knowledge of Jacques Derrida and Paul de Man trying to work (on their Macintoshes) like incompetent sign-writers.

In advocating a more complex attitude than these short-cuts backwards. I am thinking of the work of a handful of designers. They are not much celebrated, except by colleagues and satisfied clients, and are hardly known at all outside their own countries. The strength of their work comes from the fact that, for reasons of visual and material subtlety, it doesn’t reproduce well in magazines. Nor does it draw from the transnational brew of post-modernism. These weary freelance designers have little energy left over for self-promotion, and yet, although they may be working in peripheral places such as Lisbon, St Gallen and Arnhem, as well as in Berlin and Amsterdam, their work is not parochial. It speaks a language of rationality and modernity which is intelligible – though diverse and differentiated – to any sympathetic observer. Indeed, this lucidity is part of what distinguishes their work from the visual self-strangulation of ‘the new discourse’ of post-structuralist design.

To demonstrate the two directions of local versus international, it might be easier to consider buildings. In Munich there is a newspaper office and printing plant which might be termed ‘high-tech’, but which is quite different from another ‘high-tech’ newspaper office in London. These buildings have materials and attitudes in common, but their nationalities are also evident. The English architect plays a coup de théâtre with a transparent wall which lights up its barren context at night. The German architect, in an established setting, builds more solidly to produce a very well-made, ordinary structure. Or consider certain buildings in Spain and Italy that use brick in their local idioms, but which are the same time modern and international. If much of the evidence for this local-yet-international approach comes through the images shown in architectural magazines, these publications are also the forum for a global conversation about what architecture might be.

Graphic design may be essentially different from architecture, but could there be parallels here? Could there be graphic work which resists incorporation by the Euro-blender; which is local to a particular culture, and, at the same time, international in its resonance; a graphic design that, even if it sometimes finds itself reproduced in magazines, still delights and surprises when you get to inspect-touch-read the thing itself?

First published in Eye no. 5 vol. 2, 1991

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.