Friday, 9:00am

16 February 2018

Fabricated reality

Andreas Gursky’s photographs, manipulated like digital paintings, have spectacular impact. But they can display a lofty detachment from their subjects. Photo Critique by Rick Poynor

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor, written exclusively for Eyemagazine.com

What is the nature of contemporary reality and how should a photographic image-maker go about representing it? The word ‘reality’ is easy to use and applying it instantly bestows gravity on an activity or project. Reality is both the sum total of all things and the condition each of us must face. Yet the reality of our individual perceptions and experiences is that there are multiple kinds of reality, and the version of reality I inhabit, as a subjective being, may differ from the version of reality you inhabit in crucial ways, even if our circumstances are in many respects similar. Meanwhile other people, in other places, will inhabit fundamentally different realities.

For the German photographer and artist Andreas Gursky, ‘Reality can only be shown by constructing it.’ In Rhine II (1999), a photograph of the river, Gursky – the subject of a major retrospective curated by Ralph Rugoff at the newly reopened Hayward Gallery in London – edited out of the scene a coal power station and other details. The huge horizontal picture confronts us with empty sky, strips of grass and a glinting band of water. For Gursky, this manipulated tableau is an ‘accurate image’ of a modern river. ‘I am interested,’ he says, ‘in the ideal typical approximation of everyday phenomena – in creating the essence of reality.’ This statement is presented without further comment in the gallery’s exhibition guide and we are presumably meant to see it as a reliable explanation of what Gursky has achieved.

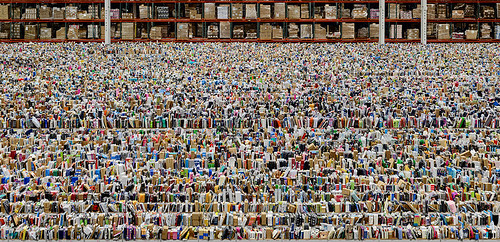

Andreas Gursky, Amazon, 2016. © Andreas Gursky / DACS, 2017. Courtesy: Sprüth Magers.

Top: Installation image of ‘Andreas Gursky’, showing 99 Cent, 1999, remastered 2009 (left), and Pyongyang VI, 2007/2017 (right). Photo: Ralph Goertz. Hayward Gallery, 25 January to 22 April 2018.

We might wonder why a river needs to be ‘idealised’. Is the essence of reality to be found in showing a subject shorn of the distractions of its particular context? Should the real be approximated when it is represented in order to perceive its intrinsic qualities, its ‘thingness’, more clearly? Gursky’s deletions have perhaps made the river more like his own subjective view of it – his reality – but in what sense is this the essence of reality for other viewers? If we could see it, we might find the coal power station to be the most salient aspect of the scene. Gursky’s statement that reality can only be shown by constructing it would be less contentious if it were prefaced with ‘my’, but that would immediately acknowledge that his representation did not necessarily constitute, for the rest of us, the essence of reality – unless Gursky is making the claim that his personal perceptions have universal validity.

Andreas Gursky, Utah, 2017. © Andreas Gursky / DACS, 2017. Courtesy: Sprüth Magers.

The immense scale of many contemporary photographs invites comparison to painting and in Gursky’s case the reference is often to abstract paintings. Rhine II brings to mind the weighty colour stripes of abstractionists such as Barnett Newman and Kenneth Noland. The Hayward show has a stunning photograph from 1993 of a carpet, where there is nothing to see but the weave, a universe of grey woollen flatness that seems to go on forever. Here, it must be said, Gurksy has distilled the essence and made the mundane spectacular in the process. A picture of the ceiling in an assembly room at Brasilia (1994), a receding grid of golden light, has the same painterly fascination. This is the post-Jackson Pollock visual style that art historians term ‘all-over painting’, where the density is evenly spread across the canvas.

Gursky’s pictures of the Tokyo Stock Exchange, the Chicago Board of Trade, a May Day rave in Dortmund, and a block of apartments in Montparnasse, Paris have the same all-over construction. The rave is pieced together digitally from many separate shots to form a vast panorama in which every dancer has the same presence. By matching shots of the Montparnasse block’s modular façade, Gursky achieves a view that the eye could never see. These are extraordinary pictures seen at full scale, requiring the viewer to move from a distant, all-encompassing position to extreme close-up to study the details, at which point the whole disappears.

Installation image of ‘Andreas Gursky’ at Hayward Gallery, showing Nha Trang, 2004 (left), and May Day IV, 2000, remastered 2014 (right). Photo: Ralph Goertz.

On a formal level it is impossible not to be dazzled by Gursky. When the pictures work, the size is vital to the effect, though almost as often these monumental images browbeat the viewer with overstatement. The pictures tend to create uncertainty about where the photographer is situated in relation to the scene because their constructional artifice means there is no fixed viewpoint. Many are shot from a god-like perspective. ‘I stand at a distance,’ Gursky says, ‘like a person who comes from another world.’ He has described his human subjects as ‘representatives of a specific species, whose mission remained obscure.’

This lofty detachment appears to be Gursky’s reality. Nha Trang (2004), a picture of chair-makers in a Vietnamese factory, erases the individuality of the workers. There are many things a photographer might choose to say about such a subject, yet Gursky bent it to suit his formalistic concerns, requesting that everyone wore the same orange T-shirt to impose visual order on the chaos of the factory floor. His technological manner of fabricating images may ‘challenge our thinking as well as our eyes’, as the curator suggests, but as a view of our societal challenges in a globalised world, his elevated perspective has notable limits.

Andreas Gursky, Pyongyang VII, 2007/2017. All photographs: Andreas Gursky / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018. Courtesy Sprüth Magers.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, Professor of Design and Visual Culture, University of Reading

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.