Thursday, 5:00pm

16 April 2020

Instant object of desire

Walker Evans

Ed Fella

Andrei Tarkovsky

Wim Wenders

Lorraine Wild

Photography

Typography

Visual culture

Critique / Photography

A Polaroid photo’s aura of ephemeral uniqueness lies in its small white frame and supercharged surface. Photo Critique by Rick Poynor

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor, written exclusively for Eye magazine.

When Polaroid stopped manufacturing film for its cameras in 2008, it looked as though the instant, self-developing picture was history. With barely a pause, though, The Impossible Project set about resurrecting the Polaroid concept and by 2010 it had launched its first films. In 2017, The Impossible Project was renamed Polaroid Originals and now a further refinement of the brand – taking us full circle – sees the classic Polaroid name reinstated. There is a thriving trade in restored original cameras, particularly the much-loved SX-70, introduced in 1972, as well as brand new kit. Meanwhile, the Polaroid picture’s history and legacy continues to captivate both those with fond memories and a generation whose idea of an ‘instant photo’ is shaped by the smartphone. An international exhibition, ‘The Polaroid Project’, has been touring since 2017 and it was on display at the MIT Museum in Cambridge, Massachusetts, until it was forced to close (like everything else) by Covid-19.

The critical difference between a Polaroid picture and a digital snap is its substance. A Polaroid is an object. There have been numerous variants, but in the most definitive form, a squarish film image (approximately 79 × 77 mm) is embedded in a white plastic frame that is substantially deeper at the bottom. Any photographic print has an added resonance that comes from its material quality, but every Polaroid, for all its smallness, possesses a glowing aura of uniqueness: there is only one copy. When Polaroids are reproduced in books, the white frame is sometimes cropped out, leaving only the image, which ends up looking like any other photo. Further damage to a picture’s Polaroid-ness happens when it is blown up for imagined extra impact. In Instant Light: Tarkovsky Polaroids (2004, see Eye 60), the Russian director’s pictures are shown at their correct size as objects, casting a slight shadow, and they gain immeasurably. The same is true of Wim Wenders’ Instant Stories (2019), where a printed simulation of a rediscovered Polaroid from his early days as a film-maker is set into the cloth-bound cover: there could be no greater enticement for a book of Polaroid pictures. The cover of Taschen’s The Polaroid Book (2008) lines up eight of them.

Andrei Tarkovsky, Myasnoye, Russia, 26 September 1981.

Top. Wim Wenders, Yella Rottländer, star of Alice in the Cities, at the top of the Empire State Building with a Polaroid of Wenders, ca. 1974.

The limited dimensions of a Polaroid are fundamental to its appeal. Tarkovsky’s pictures of country scenes and family, taken from 1979 to 1984, are miniature miracles of light, shadow and colour. They are astonishingly well composed and perfectly lit for casual snapshots, displaying the lustre and gravitas of nineteenth century paintings. Everything a viewer expects from a private picture – emotional connection, the treasuring of personal memory – is present to an acute degree. The smallness acts as a condenser, supercharging the surface area, while the permanent frame intensifies the sense of an exquisite moment caught and held.

Wim Wenders, breakfast in a coffee shop, New York, early 1970s.

Wenders makes no special claims for his Polaroids – exhibited at The Photographers’ Gallery in 2019 – as pictures. They functioned as a kind of notebook and he estimates he took 12,000, giving many of these unrepeatable originals away to their subjects as an extension of the moment of their making; only 3000 survive in his collection. There is not much sign of the superb photographer Wenders became later. He describes more or less centring the subject in the viewfinder and hoping for the best: ‘All cameras produce their own aesthetics’. Even so, these ‘image-objects’, as he calls them, appeared to him to have been stolen from the world. Each Polaroid, an outcome of a ‘little magic act’ in the camera, was proof the events it showed had happened and its singularity was central to this act of witness.

In design, the most indefatigable exponent of the Polaroid image was Ed Fella (see Eye 23), who used his 680 SE – the SX-70’s successor – to document the signs and lettering he saw on his car trips across the US. Letters on America, published in 2000, collects 1134 of these Polaroids. In retrospect, this remarkably relentless portfolio of images was somewhat overlooked, probably because, like Fella’s hyper-elastic lettering (shown in the book), it falls between the visual worlds of art and design. The book received only a short review in Eye, for instance, while its positioning as a design title meant it was unlikely to gain attention in photographic circles.

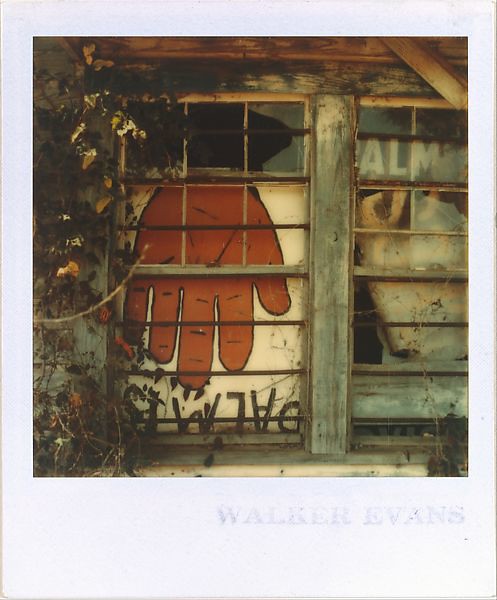

Walker Evans, Palmist Building Window, Alabama, October 1973. © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Letters on America is a cornucopia of vernacular lettering, although Fella wasn’t the first Polaroid devotee to see the potential. From 1973 to 1974, in the final years of his life, Walker Evans made Polaroids of hand-painted lettering and some were close-ups of isolated fragments. Fella went much further, treating this subject matter as a relentless programme of typographic captures, as spring-loaded with energy as his more famous flyers, despite the smallness of the image. When pointing the camera, he made no attempt to step back and view his finds in their entirety or to illustrate their roadside settings. The Polaroid is better suited to moving in close and he gains exceptional impact from his tight inquisitive framing. Unruly letterforms twist and flex, run off the edges and form semi-abstract shapes within the square. The pictures seem both casually plucked and carefully composed. By that point in the late 1980s and 1990s, the colour was more accurate than in the murky 1970s (see the Wenders book) and Fella records a panoply of hues and tones on these scuffed and battered wooden and metal surfaces.

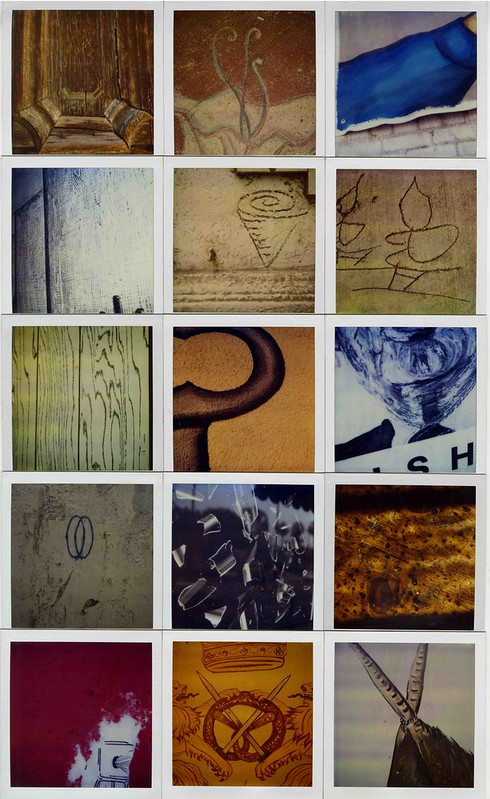

Ed Fella, page from Letters on America, 2000.

In the book, designed for Fella by Lorraine Wild, Lucy Bates’ visual edits redouble the pictures’ vitality with hundreds of spectacular collisions that reward close looking, even if the first impression could seem overwhelming. As the book’s back cover shows, the Polaroid frames are taped together to form a 3 × 3 grid that neatly fits the page. I didn’t like these visible overlaps much at the time, although cropping out the frames would be worse. Are these assemblages merely expedient or should each group of nine be considered as a work in its own right? In The Graphic Eye (2009), a book of designers’ photographs, Fella shows six Polaroid quartets from his ‘American Vernacular: Landscape Series’, woozy close-ups of countryside and buildings in old paintings. Here, he butts the frames together, overlapping them only along one edge. His archive contains numerous sheets of Polaroids of faces in a plethora of styles and often unidentifiable marks that become diminutive abstracts. Every picture is interesting, but Fella prefers to treat them as units in a montage of impressions that is always more, in image terms, than the sum of its parts.

Ed Fella, sheet of Polaroids, undated.

Yet Fella’s montages embody a paradox. The pictures cannot be entirely free as images, as he seems to wish, without eliminating the frame entirely and obscuring their material status. As with all Polaroids, the frames containing the chemical processes that formed the image are an essential part of their potency as ‘image-objects’ and, consequently, of their meaning.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, Professor of Design and Visual Culture, University of Reading

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.