Summer 2008

James Lambert

Who cares about graphic design history?

James Lambert grew up in the Cotswolds, and did a BA at Camberwell College of Arts in London, followed by an MA at the Royal College of Art, graduating in 2003.

Q1. What do you think is meant by ‘the canon of graphic design history’? Do you ever think about it, or buy design history publications?

A1. In theory, the canon should include iconic, seminal works that have influenced and shaped the course of design history. A piece may represent a movement or it may be era-defining. I suppose that the ‘canon’ has evolved through documentation, for the purpose of quotation and discussion. It’s important to see it as a basic framework that serves a purpose and is evolving, and not as a definitive list.

I don’t fetishise classic designs, as some people seem to. I place as much value on things that are one-offs, slightly odd or by people on the outside.

I don’t think about design history as a subject, though I do buy design history publications for reference.

I intuitively collect print, and veer towards the unusual or overlooked.

I get visual cues from all over, including art history. That’s not to say I am not influenced by design history. It would be impossible not to be . . .

Q2. Does design history have relevance to your practice?

A2. I accept that there is a general canon of design history (as well as personal heroes). It forms the foundations of contemporary design practice, and is therefore relevant to my work. You can never ignore it. It will always be there. Even if you make a conscious decision to ignore it, you are still acknowledging its existence. Even if you disagree with the inclusion of certain figures / pieces or believe there are gaps, it is still there and has been reinforced through hundreds of years of design writing.

I intuitively like work that has a kind of new nostalgia, that nods at something historical but adds a new slant. The familiar, coupled with something more unfamiliar, jarring or odd that may be something subtle like colour, texture or a typographic quirk, etc. Quoting design history in an interesting way suggests that there has been thought, research, knowledge underpinning its design. Obviously quoting history without questioning why it is appropriate can result in hollow pastiche. I don’t like things that are retro but that may be because the term retro, ironically, seems outdated.

Q3. Where did you learn about design history?

A3. I think that I was mostly taught art history with reference to design, throughout my arts education (school, foundation, BA, MA).

Q4. Does history have any relevance to the new technology and techniques you’ve had to master in your work?

A4. No matter what the technology or tools you are using, rudimentary principles still apply. You can tell if something is considered, and that is timeless. I will always hand-draw what I am designing / illustrating first before touching any new technology.

Q5. If you were in charge of a design education programme, what aspects of design history would you teach?

A5. It is important to learn the fundamental principles of design with reference to historical material. It is good to have a framework to fight against and some rules to break.

I would try to promote practice driven by ideas. It is important to know about what preceded, if only to inform / encourage progress.

I would nurture individual visual language through exposure to the history of other artistic fields. I think that it is important to encourage designers to have their own agenda.

I am sure the designers who are now part of ‘the canon’ had their own.

It’s good to learn about the context of design classics and the framework in which they sit – to see them not just as iconic, in some kind of bubble, but being created for a reason. This gives insight into the mechanics of the design process.

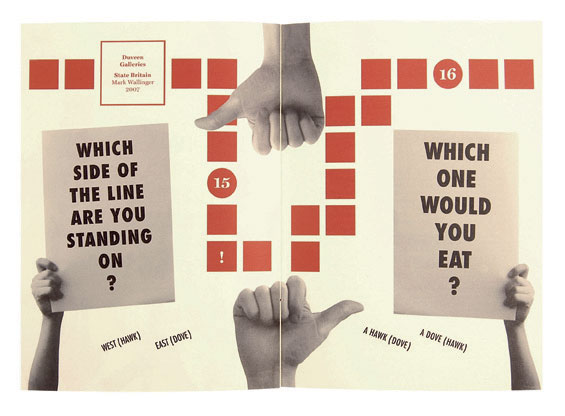

Top: Spread from War Path. A project for Tate Britain, a curated walk around the gallery. Extreme repetition of a familiar propaganda motif, based on the feel and size of a ration book. Design: James and James, James Lambert and James Graham, 2007.

First published in Eye no. 68 vol. 17 2008

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.