Winter 2006

No animals or models were harmed…

Vogue’s fusion of high fashion with brutish behaviour besmirches readers by making abusive images acceptable. Critique by Rick Poynor

In the usual way of things, I would have missed the September issue of Vogue Italia. I don’t read Italian and I find the posturing of the fashionistas easy to live without. Then I saw The Guardian’s short, angry piece about Steven Meisel’s ‘State of Emergency’ fashion shoot, illustrated with three spreads and the headline ‘A taste for torture?’ next to a picture of the magazine’s front cover.

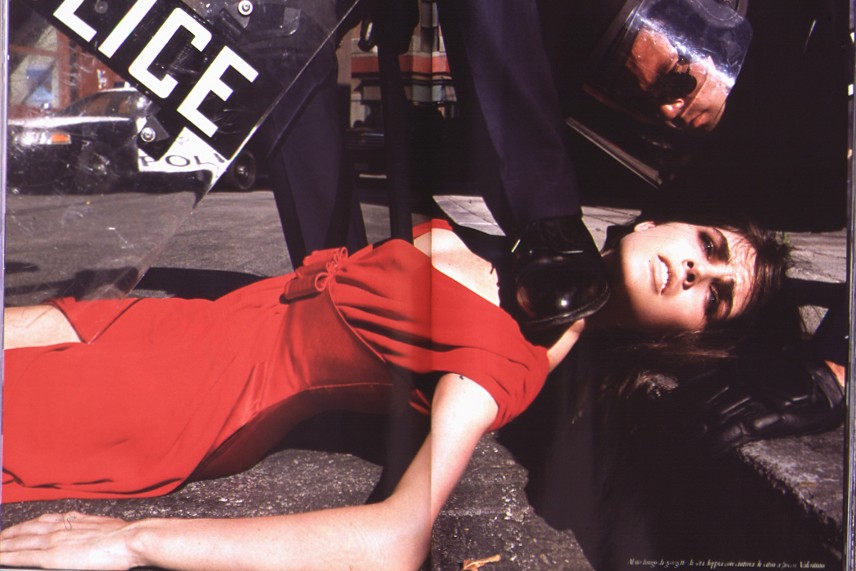

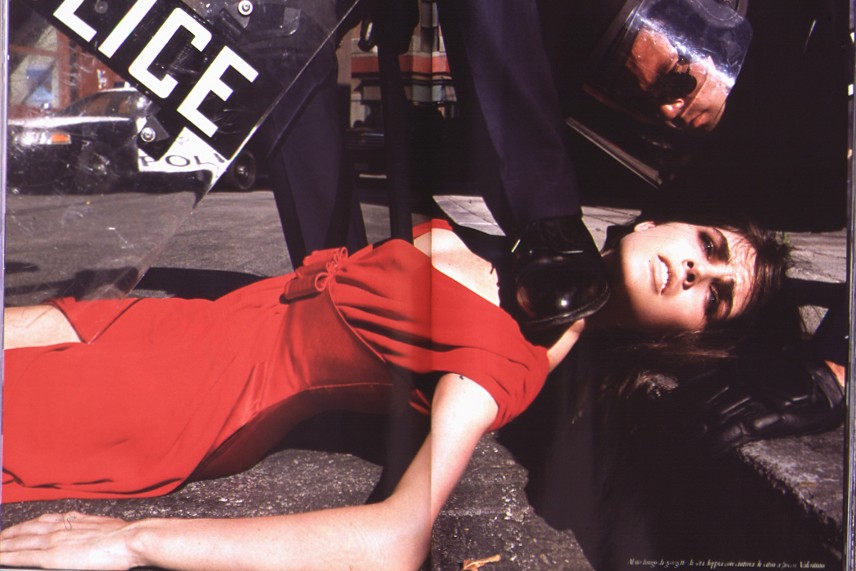

The Guardian’s picture editing – it might almost have been an Eye Critique – did everything to play up the torture angle. In one shot, the model steps out of her skirt as three uniformed security guards look on. In another, she is on her knees with her hands behind her head. A guard wields a big phallic truncheon and a dog barks at her. To remind us where we have seen dogs like this before, the paper ran a 2003 shot of a dog menacing a detainee at Abu Ghraib. In the most alarming photo – a picture that shames the photographer, Vogue Italia and its publisher – a policeman’s boot presses down on the throat of the same model, who lies in the street with her head on the kerb.

Spreads from Vogue Italia, September 2006, Photographed by Steven Meisel. Art director: Luca Stoppini

The article by Joanna Bourke, professor of history at Birkbeck College, ramps up the outrage. The pictures ‘take the pornography of terror to another extreme’, she writes. This was fashion photography serving ‘the interests of the politics of torture and abuse . . . There is a vicarious satisfaction in viewing these depictions of cruelty in the interests of national security.’

When viewed in context as part of the 30-page story, the pictures seem less shocking. For one thing, their artifice and absurdity become clearer. Taking your skirt off in the public area of an airport, after passing through a metal detector, is no more realistic and plausible than having to submit to a public body search in your bra – shown in another picture. There are, in any case, several narratives running through the story. In one series of pictures, we see a blonde practising her shooting skills with some ‘good guy’ cops at a firing range. As a commentary on the climate of terror reported and reinforced by the media – if that is Meisel’s aim – the pictures are risible. Yet, while the throat-crushing shot is inexcusable, it is an overstatement to suggest that torture is the story’s pervading theme. The mislabelling is an unfortunate case of crying wolf because, as The Guardian rightly noted, torture imagery is steadily being normalised.

Ever since the prominent US attorney and law professor Alan Dershowitz and others started talking about hypothetical ‘ticking bomb’ scenarios in which it might be justifiable for the United States to use torture, this formerly taboo idea has been surfacing in popular culture. Jack Bauer, maverick hero of 24, resorts to torture whenever he finds it expedient. In Lost, Sayid, a former Iraqi Republican Guard member and accomplished torturer, is also ready to turn violent when someone’s tongue needs loosening. Both men are presented as attractive figures.

The horror film Hostel, a big hit with home audiences at Blockbuster this summer, exults in the possibilities of torture as entertainment. The American campaign poster enticed viewers with some almost tasteful-looking pincers; the Germans opted for a power-drill descending into a mouth; and the Italians went all the way with a man dangling a woman’s severed head.

For video-gamers, the new Reservoir Dogs provides an invitation to try out the role of torturer, cutting off fingers and burning eyes. Dr Nimisha Patel, head of clinical psychology at the Medical Foundation for the Care of Torture Victims in London, has expressed deep concern about these developments. ‘The depiction of torture in video games not only trivialises torture,’ she says, ‘but it serves to normalise acts of violence prohibited by international human rights and humanitarian law.’

Meisel’s shoot drew mixed reactions. Some viewers deplored the pictures; some noted that this kind of trivial play-acting is routine in fashion and not to be taken seriously; and some seemed more concerned about whether the images were effective as titillation or not. The pictures are comparatively mild, and rather silly, but nothing positive can come from public flirtation with images of abuse. As the Medical Foundation observes, any media entertainment that glorifies the infliction of pain ‘adds to a culture of indifference, disbelief and acceptance of torture’. Such imagery is softening-up propaganda for a political development that besmirches us all.

Rick Poynor, writer, founder of Eye, London

First published in Eye no. 62 vol. 16 2006

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.