Spring 2007

Out of the ordinary

Banal, amateur snapshots become almost poetic in these books by Fiona Tan

There is something a bit too worthy about the way that artists – or maybe it is just art critics labouring to say something profound – talk about the uses artists make of private photographs taken by ordinary people. They like to sprinkle the discussion with words such as ‘memory’ and ‘identity’, ‘ethnographic’ and ‘archival’, as though looking at these images automatically engaged the viewer in an act of sociological research.

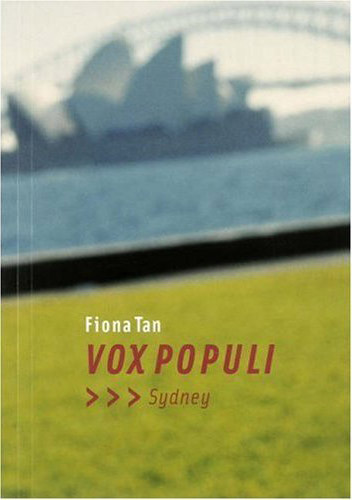

Was this what motivated me to obtain Fiona Tan’s two new books of photos from the private albums of Norwegians and residents of Sydney when I saw them in Book Works’ catalogue? I’m afraid not. I was hoping for images that packed the kind of deadpan intimations of mystery often seen in found photographs and vernacular photography. The cover of Vox Populi, Norway, showing the bonnet of a car on an empty road that leads towards snow-covered mountains, certainly did it for me. Why is the mauve of the Tarmac so exciting and even moving, in a peculiar way? I can’t quite say – but it is.

The Norwegian project came about when Tan, an Indonesia-born artist based in the Netherlands, was asked to create a wall installation for the Parliament in Oslo. Travelling around the country, she selected photos from the albums of about 100 volunteers. Vox Populi, Sydney developed in the same way: 90 or so citizens gave Styles her access to their photos, which she then used to make a wall for the 2006 Biennale of Sydney. The books, designed by Gabriele Franziska Götz, who also collaborated on the picture editing, give the project another dimension as vernacular documents.

Each volume is divided into three sections: portraits, home and nature. All the images are cropped to the same size – slightly narrower than a 35 mm shot – and this gives the books visual continuity, while sacrificing some of the personality that would come from showing pictures in different formats. It also means that the editors can make small degrees of compositional correction, which seems counter to the documentary spirit of the enterprise. There are subtle differences in layout, too. The average picture size is smaller in Vox Populi, Norway and there are more spreads with groups of related shots; the pages feel richer and other factors also make the book more engaging as a collection.

Statistically unlikely as it might sound – these are amateur photos, after all – on this evidence the Norwegians seem to take better snaps. Pictures in both books show everyday scenes that might occur anywhere – sleeping babies, family gatherings, toddlers in the bath, children playing with hoses in the garden – yet the Norwegian shots tend to be sharper and clearer, with brighter colour. They are often quirkier, too, and the editors take full advantage, as in a spread showing two pictures of babies, where we can ponder the contrast between a shiny purple quilted cover and the softer sheen on a black leather sofa. The Norwegian collection features shots of tables laden with food and drink – not that far from Martin Parr land.

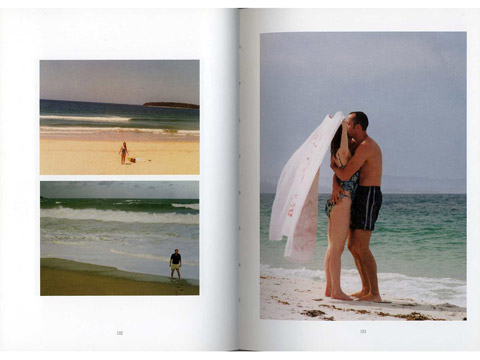

Vox Populi, Norway also has moments of outright weirdness. A naked three-year-old wearing face paint looks less than delighted by the birthday cake a hand is pushing his way. Meanwhile, in the countryside, a person (gender unknown) takes a rest next to a reindeer’s decapitated carcass and scattered entrails – that must be quite a photo album. In another Norwegian picture, a young woman in traditional costume poses gravely in front of a towering mass of aquamarine-tinted ice and snow. By contrast, in the Sydney book, shots of Australians enjoying the beach and clambering on ancient rocks in the outback look like the kind of dull

‘I was there’ tourist snaps that anyone might bring home; and, to an ethnographic way of thinking, this is probably the point. So much of our behaviour, and the way we record and remember it, is utterly ritualised.

There is a recurrent tension in these collections between the banality of the everyday experiences that everyone shares – mowing the lawn, attending a wedding, dozing off next to your dog – and the moments when, pictorially at least, a hint of something more idiosyncratic or inexplicable emerges. In one sequence, the photographers catch three figures off guard, their faces hidden by clothing, a door, or a turned back. The mere fact that somebody bothered to keep and display pictures that are ‘failures’ suggests a way of seeing things that goes beyond the usual clichés of content and composition. If it didn’t seem so unsociological, and for that matter trite, you might even call it a kind of poetry.

Below and top: Cover and spread from Vox Populi, Sydney by Fiona Tan (Book Works, 2006).

Rick Poyner, writer, Eye founder and research fellow, Royal College of Art, London

First published in Eye no. 62 vol. 16 2006 Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.