Summer 2014

Readymade format

Marcel Duchamp

René Magritte

Roman Cieślewicz

Andre Breton

Luke Frost

Therese Vandling

Jindrich Heisler

Klaus Voormann

Tony Wright

Design history

Visual culture

An illustrated ‘gift book’ dictionary by Heretic brings Marcel Duchamp’s ideas to a wider audience. Critique by Rick Poynor

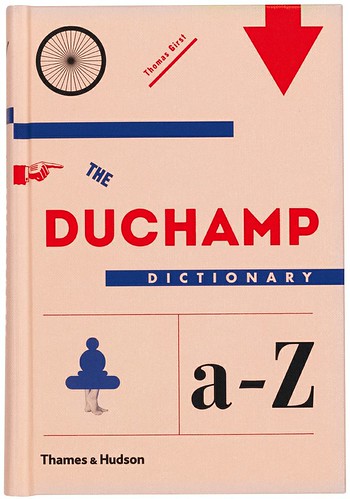

The art world’s enthusiasm for the dictionary as a highly adaptable container for all kinds of content shows no signs of abating. Since I wrote about the subject in ‘Love of Lexicons’ (Eye 78), the format has been used in catalogues for René Magritte at Tate Liverpool (2011) and Surrealist objects at the Pompidou Centre (2013). Now comes The Duchamp Dictionary by Thomas Girst for Thames & Hudson. With a printed hardback cover decorated with Dadaistic motifs, and a fancy page-marker ribbon, the book melds library-shelf sturdiness, practicality and readability with something close to spur-of-the-moment ‘gift book’ appeal.

It’s a clever piece of packaging, calculated to bring Marcel Duchamp to the attention of a new audience. ‘For too long,’ Girst writes in the intro, ‘art historical discourse has kept a broader public from enjoying the life and work of one of the most intellectually stimulating individuals of modern times.’ Within the art world, Duchamp is regarded as one of the greatest artists of the twentieth century, a figure to set alongside Picasso. In an entry on ‘influence’, Girst fills two columns with a list of artist devotees. But it’s still hard to imagine a Duchamp retrospective generating the ecstatic reception that has greeted, for example, Matisse’s cut-outs at London’s Tate Modern. As Girst notes, despite the eroticism and humour of his work, much of the discussion surrounding Duchamp has been impenetrable.

Girst even uses the word ‘entertaining’ when stating his aims. The entries are generally short and packed with information, with many quotations from Duchamp, whose remarks are always great value. For instance: ‘I consider taste – bad or good – the greatest enemy of art.’ Or: ‘There is no solution because there is no problem’ – try that one as a design mantra. When his friend Edgard Varèse died, Duchamp sent the composer a telegram saying, ‘Dear Edgard, see you soon.’ The chess-playing ‘an-artist’ – his preferred term, meaning ‘no artist at all’ – embraced chance, puns, replicas, contradiction, laziness (‘I like living, breathing, better than working’), chocolate, smoking, indifference, and the aesthetic value of boredom.

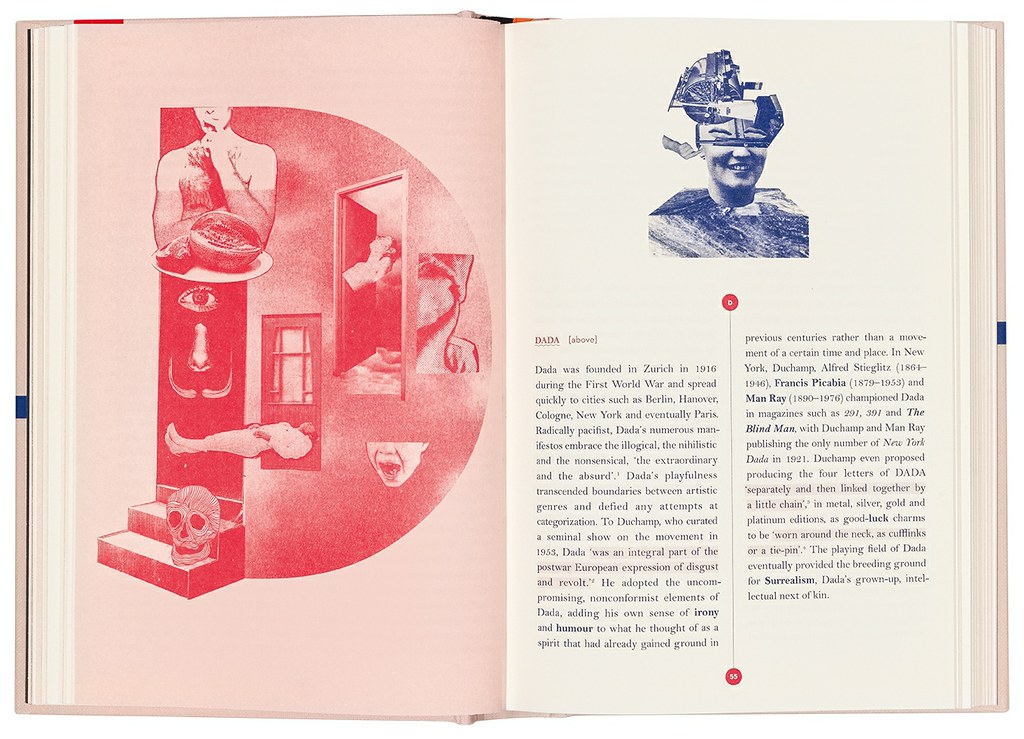

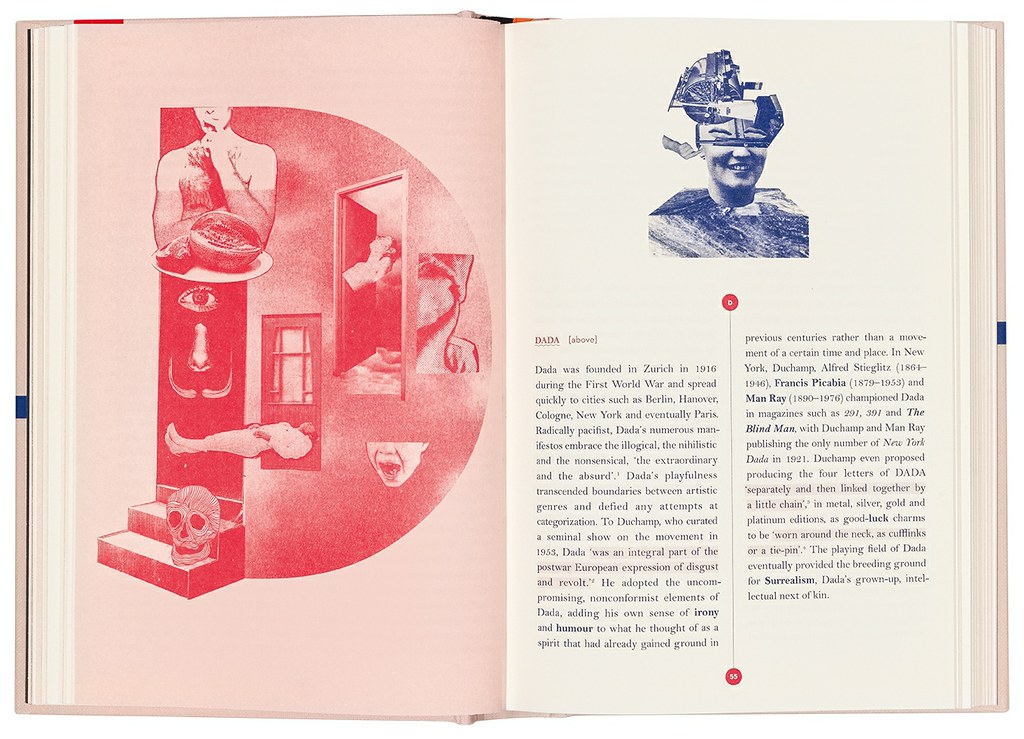

After the cover, the most arresting thing about the dictionary is the way it is illustrated. Instead of photographs of Duchamp and his work, it contains 68 images by Luke Frost and Therese Vandling of Heretic; Vandling is also the designer. Each of the alphabetical sections has its own decorative initial, fashioned from collage and drawing – these recall the Surrealist alphabets of Jindrich Heisler and Roman Cieślewicz – and many entries receive full page illustrations. No reason for taking this approach is given, but it must have been relatively simple to organise compared to international picture research, and doubtless cheaper, too.

In style, the illustrations take their bearings from classic Surrealist collage, Klaus Voormann’s Revolver LP cover, 1960s psychedelia, and the posters of M / M. The numerous rectilinear shapes with clouds for sides imply at least a passing acquaintance with Traffic’s The Low Spark of High Heeled Boys – Tony Wright’s cover artwork from 1971 even has a chessboard base. At first sight, this whimsical imagery doesn’t seem especially Duchampian, although Duchamp was always sympathetic to Surrealism, which he lauded as ‘the most beautiful dream of a moment in the world’, without ever joining the movement. His ambivalent but ultimately admiring relationship with André Breton merits a long entry, equalled only by the one for ‘Readymade’. On the other hand, any attempt to pastiche the formal inventions of Duchamp’s Large Glass would be bound to fail, and the more literal references here, such as figures with bicycle wheels for heads, tend to grate. Given the conceptual challenge posed by some entries – optics, onanism, the fourth dimension, and the elusive ‘infrathin’ – surrealistic imagery makes sense.

While the general impression is pleasing, over the course of the book the visual ideas become repetitious and strained. After a blizzard of disembodied eyes, the only thing left for Heretic to do in the entry about vanity is to make the eye in the mirror even bigger. Some nudity is justified – there are entries on eroticism and breasts – but the illustrators smother Duchamp’s teasing refinement with a bordello of flesh. When the illustrations convince, as they do in entries about boxes, hair and the artist’s concept of a ‘transformer’ (oddly, one of the slighter texts), they tend to be constructed from a kit of images fully wired to the interpretative task.

Where the book seems an unqualified success is in Vandling’s engagingly delicate page designs. The use of red and blue for the text, the highlighting of the quotations, the wavy underscores beneath the entry headings, together with other typographic details, make this a guide to Duchamp unlike any other. It is good to see such a significant subject opened up imaginatively for a broader readership.

Cover of The Duchamp Dictionary.

Top: Illustrations by Heretic in spreads from The Duchamp Dictionary by Thomas Girst, published by Thames & Hudson, 2014. Design by Therese Vandling.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, London

First published in Eye no. 88 vol. 22 2014

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. You can see what Eye 88 looks like at Eye before you buy on Vimeo.