Winter 2011

Regeneration X

Laura Oldfield Ford’s grainy Savage Messiah brings new urgency to an updated punk aesthetic. Critique by Rick Poynor

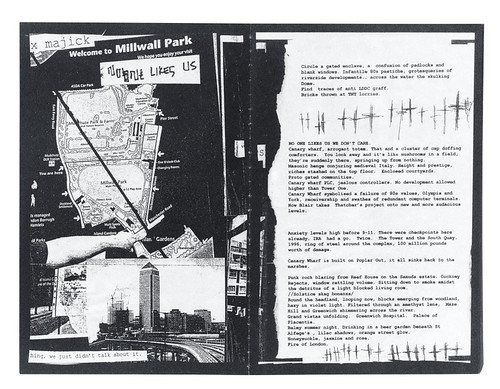

Savage Messiah by the British artist Laura Oldfield Ford (Verso) is a work for desperate times. Originally published as a series of zines, which gained a cult following, the eleven sections log Ford’s hyper-aware drifts through the ‘invisible circuitry’ of a London in the grip of neoliberal, pre-Olympics regeneration that seeks to eradicate or exclude everything unsightly and unproductive. ‘London 2012,’ she writes, ‘who wants it except for middle England pricks in their executive homes …’ As Ford traverses the Isle of Dogs, the Westway, Lea Bridge, King’s Cross, Hackney Wick, Canary Wharf and Heathrow, she is alternately furious and tender, and her writing, images and layouts twist, buckle and surge with an energy that’s both violent and ecstatic.

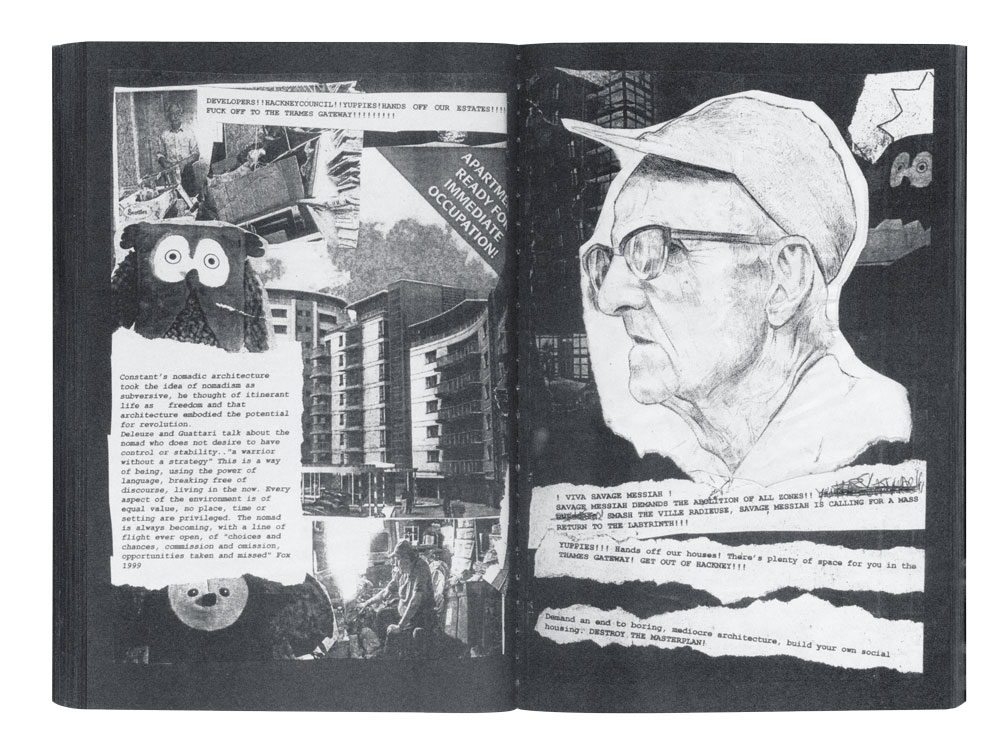

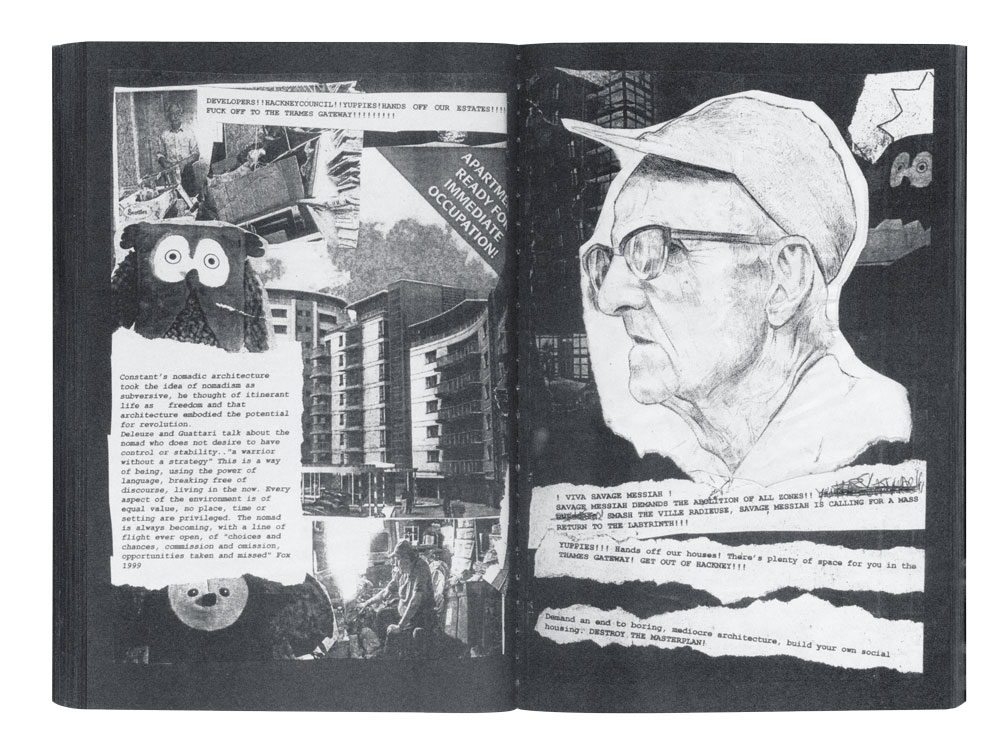

The visual style is a kind of reclaimed punk that recalls the anarchic graphics of Crass around the time they released their EP The Feeding of the 5000: harsh black and white, torn and jagged edges, collage artwork, grainy photocopier resolution, funereal black borders around everything, and urgent typewriter for the text. The scabrous, scissors-and-paste expediency couldn’t be further from sleek contemporary digital aesthetics but it doesn’t feel nostalgic or retro (though it’s certainly mournful) because of the way Ford zigzags through time – 1973, 1981, 1990, 1999, 2001, 2013 – capturing the experiences, energy and dreams of dissenters who refuse to play the yuppie game and knuckle down. ‘This decaying fabric, this unknowable terrain has become my biography,’ she writes, ‘the euphoria then the anguish, layers of memories colliding, splintering, reconfiguring.’

Above: Spread from Laura Oldfield Ford’s Savage Messiah issue 1, ‘Welcome to the Isle of Dogs’, June 2005.

Top: Spread from issue 7, ‘London 2012 Death to the Gods of Mount Olympus!! Yuppies!! Hands off Hackney’, undated.

The book is soundtracked with music references – U. K. Subs, Cock Sparrer, Flux of Pink Indians, Throbbing Gristle, Cabaret Voltaire, Test Dept, Heaven 17 – and spliced with apt quotations from Chris Marker, Italo Calvino, Guy Debord, J. G. Ballard’s High-Rise and Concrete Island, and Mike Davis’s City of Quartz.

Ford’s writing, sometimes delivered in fast telegraphic bursts, sometimes at greater narrative length, is acutely observant. In Burroughs-like cut-ups, she switches between episodes from her own life that could be literal or embroidered, and scenes that could be based on things she has heard or even purely imaginary.

Her texts tend to become more expansive as the series progresses, with whole pages and spreads of prose. Greater continuity makes the writing easier to read, although the heavy, unvarying weight of typewriter text can be a slog at this reduced scale (the originals are A4). In the context of the book, inconsistencies of method and grain that might have gone unnoticed from issue to issue become more obvious. Ford was at her most graphically uninhibited at the beginning and, viewed in those terms, the hyperactively fragmented and immersive first issue (June 2005) emerges as one of the best. Later issues are not so layered.

Ford’s assertively linear style of drawing plays an essential role in personalising these pages. She is good at faces, which are strongly characterised, and deftly captures the downbeat greyness of walkways, flyovers and tower blocks. In the fourth issue (April / May 2006), visually the least enlightening, she goes overboard with self-portrait drawings. Elsewhere, she includes photographs of herself and a painting in which she stands on a chair next to an oil barrel wearing high heels and tracksuit bottoms, with her hand on her hips. A disturbingly prophetic note of violence and disorder simmers below the surface of Savage Messiah.

In another self-portrait with attitude, Ford poses next to the words ‘Ultra Violence’ and ‘Riots!’ She tells East Enders sick of being ‘pogrommed’ out of their estates by yuppies that the solution lies in their own hands: ‘Wreck it! Loot it! Burn it!’

Tongue-in-cheek provocation or not, these zines appeared long before the British riots of 2011. Embedded at ground level, Ford exposes a dispossessed, deeply disaffected alternative London to which out-of-touch political masters should have paid more heed. ‘Savage Messiah is written for those who could not be regenerated, even if they wanted to be,’ writes Mark Fisher, author of Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?, in the introduction. ‘They are unregenerated, a lost generation.’

Is Savage Messiah’s exhilarating fusion of media a sign that psychogeography, as a way of investigating the city is not, as Fisher suggests, entirely played out? Ford is scornful that the Situationist term has been co-opted by ‘middle-class men acting like colonial explorers’. But she still put it on the cover of issue 9 – ‘The Psychogeography of Paranoia’ – and uses the related term dérive, defined elsewhere as a ‘rapid passage through various ambiences’. Fisher prefers the word ‘hauntology’ to describe how intense moments from the past, the vibrations that Ford mourns, cling to the places they touched. In the penultimate section, she drifts through the imaginary abandoned ruins of a libidinal, post-Olympics London stripped of its billboards, newsagents and former hypocrisies. Fantasy, metaphor, or storm warning? Savage Messiah is graphic literature of great urgency.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, London

First published in Eye no. 82 vol. 21, 2012

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue. You can also browse visual samples of recent issues at Eye before You Buy.