Winter 2017

Relentless riches

Manfred Heiting

Book design

Graphic design

Photography

Critique / Photography

Front matter

A busy blockbuster traces the stunning history of Japanese photobooks. Photo Critique by Rick Poynor

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor, written exclusively for Eye magazine.

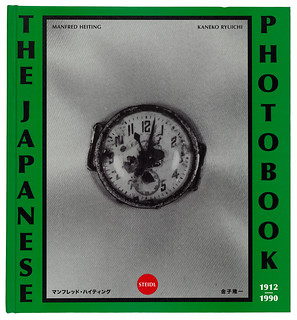

The celebration of the history of the photobook – noted in a previous Critique – continues to produce volumes of spectacular ambition and panoramic sweep. The latest arrival, The Japanese Photobook 1912-1990 by Manfred Heiting and Ryuichi Kaneko, is a 570-page shelf-buster to set alongside Heiting’s previous project, The Soviet Photobook (2015), also published by Steidl, and The Chinese Photobook (2015) by Martin Parr and WassinkLundgren, published by Aperture.

These surveys generate great anticipation for anyone interested in photographic history. Since around 2000, they have helped to establish the photobook as an object of close critical attention, challenging the art-world consensus that the optimal space to look at photographs is removed from their original printed contexts (assuming they had them) on the gallery wall. The photobook now stands revealed as often the most concentrated and potentially effective way for photographers to disseminate their photographs, surpassing even the magazine. As these compendious overviews show, this has been the case around the world. Yet the scale of production and the national histories were previously hidden, and it is only now that we can assess how significant as a medium the photobook has been.

Heiting and Kaneko’s book isn’t the first survey of Japanese photobooks, but it’s the first to travel back to 1912 and the widest in scope. While it warehouses more than 3500 images devoted to 511 projects, the authors readily concede that much archaeology remains to be done. Even so, they have exciting early chapters on pictorialism from 1914 to 1937, avant-garde photography influenced by the new photographic vision of the 1920s and 1930s, and mid-century photojournalism and propaganda.

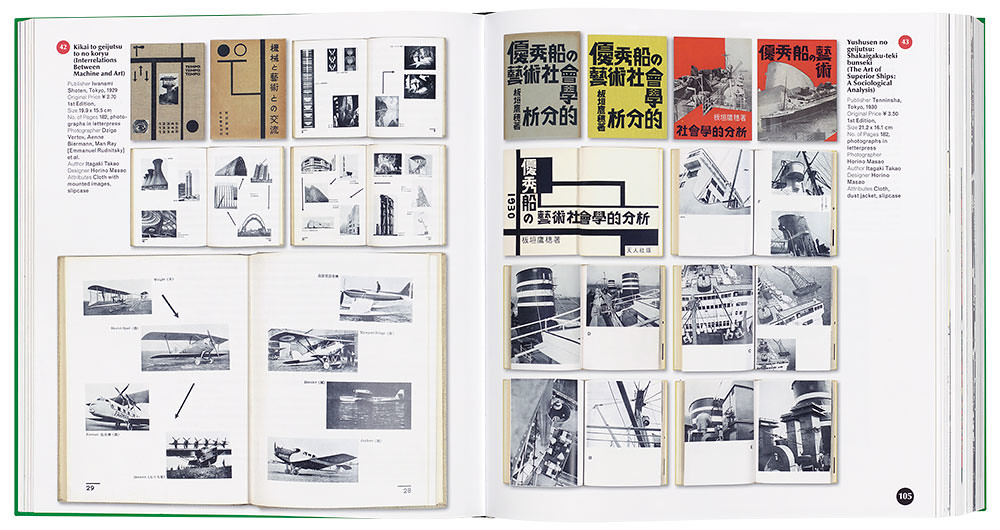

One revelation, allotted many pages, is the magazine Front, which was like a Japanese take on USSR in Construction, complete with English text, only devoted to the war in the Pacific.

Spread from Front, nos. 3-4, Tohosha, 1942, showing photographs by Ihei Kimura, Hiroshi Hamaya, Tsutomu Watanabe and Shunkichi Kikuchi, among others.

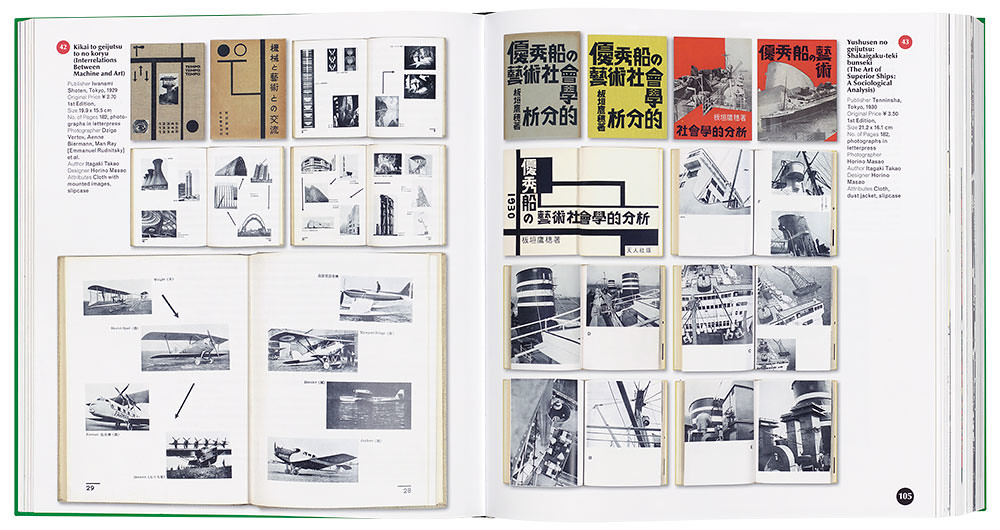

Top. Spread showing Kikai to geijutsu to no koryu, 1929, and Yushusen no geijutsu: Shakaigaku-teki bunseki, 1930.

Given the great wealth and availability of material, the authors clearly took the view that they should go for abundance and even excess. The tendency with books about photobooks has been to organise the material by page unit, spread or longer sequence, with a brief text introducing each book. The Chinese Photobook is exemplary in its visual pacing and the examples are surrounded by ample amounts of white space (it also benefits from even bigger pages). The Soviet Photobook, designed by Heiting, is denser, with less space between images, but it has enough air and each photobook’s visual narrative emerges with clarity.

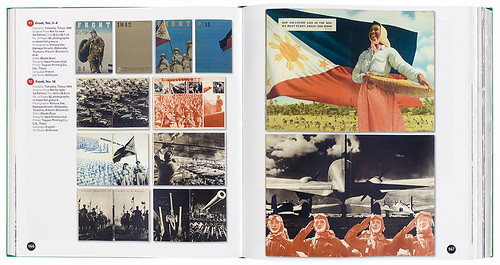

Spread showing photographs by Kazuo Kitai from Jiyu O warera ni, Nobel Shobo, 1968.

In his design for The Japanese Photobook, Heiting opts to cram his spreads with pictures – ten on a page is not untypical – leaving room for only 4 or 5mm gutters between the images. Shadows pull the exhibited books even closer together. The surfeit of imagery strains against the edge of the page, which often makes a book feel overcrowded. Many of the photos end up too small and the books’ subtleties and strengths are obscured, as the selected pages battle with each other for attention. With visual pauses and empty space at such a premium, Heiting’s over-sized caption typography feels strangely coarse; he also places item and page numbers in unsubtle discs. Unusually for this kind of survey, the individual photobooks lack explanatory texts, making the relentless flow of pictures appear even more disorientating.

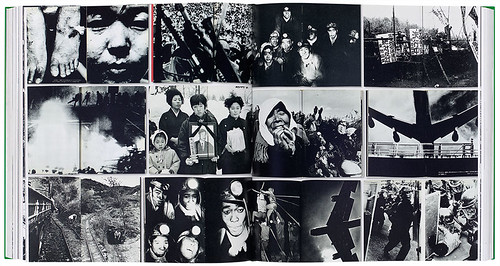

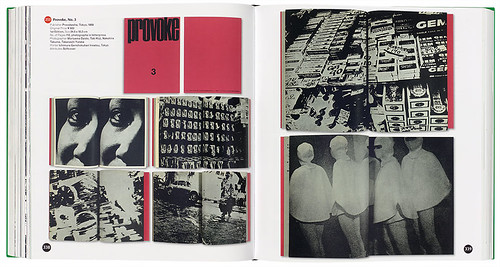

Spreads from Provoke no. 3, Provokesha, 1969, including photographs by Daido Moriyama, Koji Taki, Takuma Nakahira and Yutaka Takanashi.

It may be that Heiting judged this shoehorning approach to be fitting here. Photographs from the 1960s and 1970s by protest photographers and contributors to Provoke magazine (subject of a recent exhibition in Paris and a monograph) – figures such as Daido Moriyama – are famously full on and immersive, bleeding the pictures on all edges. Heiting tells a story about John Szarkowski, influential director of photography at the Museum of Modern Art, informing a Japanese magazine curator in 1974 that a good photograph always needs a white border. This was duly reported in Japan and photographers seeking international acceptance began to publish their images in pools of white space. Later Japanese photobooks in this now universal style are notably weaker.

‘Tragically, the uniqueness of Japanese vision in the photobook disintegrated and never again revived,’ writes Heiting in his preface. His gorged-to-bursting layouts are possibly intended to honour the spirit of classic Japanese photobooks before they lost their way.

Postwar Japanese photography has an incredible energy, emotional impact and power to shake the viewer. These image-makers were masters of black and white. Unexpected angles and startling close-ups circumvent the possibility of detachment and plunge the observer pell-mell into the picture’s world. If the book’s method of layout leaves something to be desired, it remains a volume packed with stunning images from one of the world’s indisputably great photographic cultures.

Cover of Manfred Heiting and Ryuichi Kaneko’s The Japanese Photobook 1912-1990, published by Steidl.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, Professor of Design and Visual Culture, University of Reading

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.