Tuesday, 12:00am

31 January 2012

Scarcity and silence: Amc2 Journal

An image-led journal marries the serendipitous collisions of image-sharing sites with the physicality of print. Critique by Rick Poynor

Web-only Critique written exclusively for eyemagazine.com

Our insatiable hunger for images is a peculiar thing. We can never have enough of them. We progress urgently to the next meal without having fully digested the last. How much can you eat? It’s like a kind of race that often doesn’t seem to be driven by anything greater than the need not to be caught out, so that when someone mentions something that stands every chance of being forgotten tomorrow you can breathe an inward sigh of relief and say, ‘Oh yes, I’ve seen that.’

Life online has taken this to a new level of obsessiveness. Sites like 50 Watts and But Does It Float certainly perform a kind of service by showing us interesting images we might not have seen. I just checked But Does It Float and today it has photos of coloured smoke followed by paintings by Scott Greenwalt followed by drawings by Moebius followed by … the big images look great (as always), there are cool poetic headlines and links to follow if you really must have information. Maybe later. Down you scroll. The container has only the most basic shape. It’s like a big white pipe down which the image-stuff gushes in an endless stream.

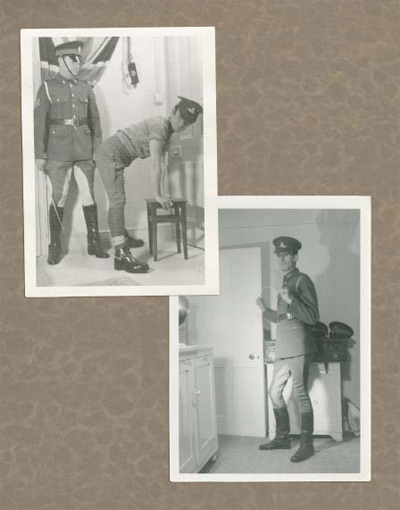

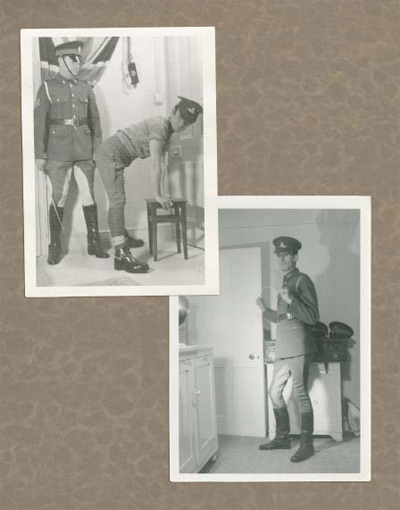

Top: a spread from ‘an archive of the Royal Horse Artillery’ taken in the 1960s.

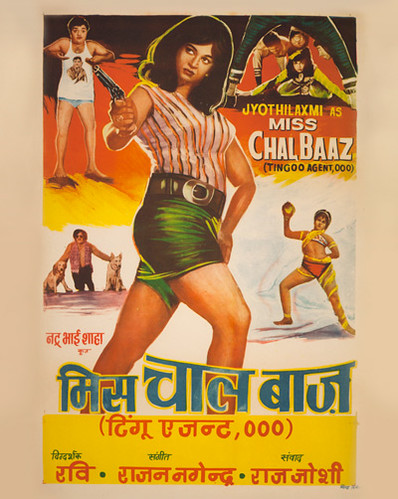

Where does this leave a printed publication like the first issue of Amc2? In some ways, the journal, published by the Archive of Modern Conflict, might seem to be part of the same phenomenon. It caters to a readership presumed to be fascinated by images of every kind and the sheer range of material within its 152 pages exceeds that of any site I can think of online. One minute you are studying nineteenth-century photographs of the bell towers of Ireland, and then, with a mighty crash of gears, the focus switches to a Rock Hudson cut-out book issued in 1957 by Universal Pictures (dress the film star as a diver, cowboy or city slicker). Within a few pages, it’s time to sober up with some hand-painted silver gelatin prints of cranial-restorative surgery produced in France during the First World War.

The visual stories, some only a single image, follow each without obvious linkage, or in some cases any form of preamble. One of the journal’s most mysterious inclusions, though that’s saying something, is a seven-page selection from ‘an archive of the Royal Horse Artillery’ taken in the 1960s. The photos show the men posing indoors in their uniforms; the shots are homoerotic, even kinky, and were clearly taken for private purposes. In a picture that resembles a missing scene from Monty Python, synchronised riders mounted on static wooden horses practise keeping their balance while leaning backwards in their saddles.

What sets the AMC and its journal apart from many of the Internet’s image channellers is that it is a real, though private, archive in Kensington, London, grounded in tangible things. Each story has a code number relating to the archive’s cataloguing system. Initially devoted, when it began in the late 1980s, to photos of war and conflict, the collection now encompasses all kinds of material ‘dating from prehistory to the present day.’ Several years ago, the AMC became a publisher of notable photography books such as Nein, Onkel (2007), which showed Nazi soldiers off-duty, and The Corinthians, (2008), a collection of Kodachrome slides.

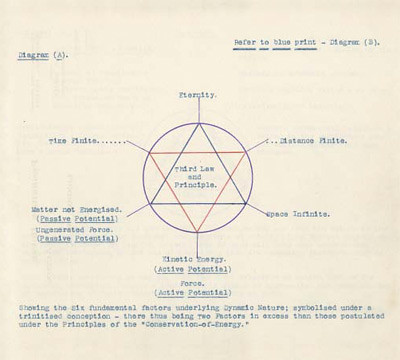

Amc2 aims to ‘illuminate lost corners of our cultural life’ and for many of the image sequences the editors provide well-written and informative introductions. Without this context, postcards of early twentieth-century Belgian dog carts, and photos of Gordon Earl Adams’s time machine, supposedly constructed in the late 1920s in the basement of his house in Shepherd’s Bush, would be merely whimsical (man and machine seem to have disappeared without trace). Amc2’s opulently image-filled pages strike a finely calculated balance between discovery and enchantment, elucidation and pleasure.

The assertive yet restrained typography and layout underscore the project’s seriousness of purpose. The journal marries the serendipitous collisions of online image-sharing sites with a commitment to editorial selection and shaping and the physical embodiment of meaning on paper. By enshrining a few choice artefacts in print, AMC makes a more persuasive claim for their historical interest and documentary value than if it were to unleash a boundless, context-free and ultimately self-cancelling stream of immaterial jpegs online.

The journal contains no credits for editing, writing or design. I asked about this and was told that it reflected a team effort. The AMC website gives no information about the archive’s history, or about its editors, Timothy Prus and Ed Jones, who are notoriously hard to pin down. This might be deliberate mystification to provoke interest, or simply a true expression of who they are. Scarcity and silence: it makes a bracing change from the unstoppable flow.

University of Toronto Physiotherapy Course press photo, Ronny Jaques, National Film Board of Canada, 1944.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, London

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.