Friday, 12:00pm

17 August 2018

Scenes from an imperfect world

Even Don McCullin expressed doubts about his photographs of war and suffering. What is their message today? Photo Critique by Rick Poynor

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor, written exclusively for Eyemagazine.com

Delving into the archive of Camerawork magazine, which Four Corners has recently digitised and put online, I came across a feature titled ‘The Photographer as Hero’ published in 1977 in issue 7. The article by the late Tom Picton, a photographer and lecturer at the Royal College of Art, focuses on the work Philip Jones Griffith and Don McCullin, who had both taken pictures in Vietnam. There is a short introduction followed by an interview with Jones Griffith and then a full page devoted to a critical assessment of McCullin prompted by a recent TV programme, Just One More War, in which he had spoken, as he has continued to speak, with disarming frankness. Picton suggests that McCullin was ‘either too honest or naïve’ and that the film-maker, Jana Bokova, had set him up ‘to make such a confession’.

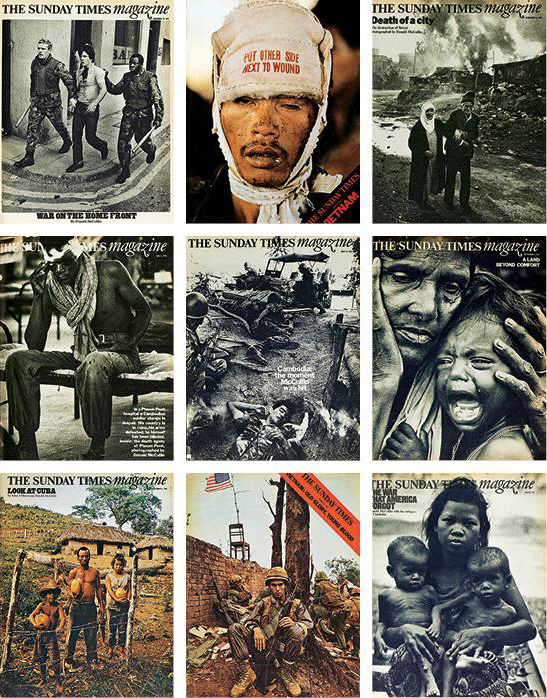

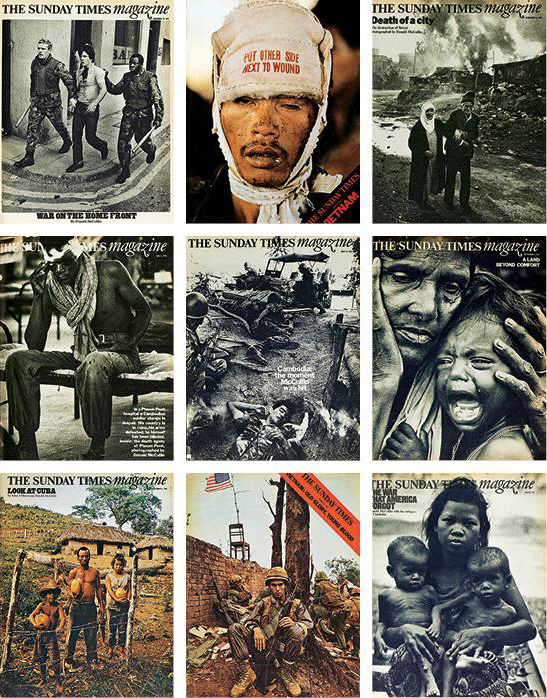

By that time, McCullin had been working for The Sunday Times Magazine for eleven years and most of his pictures of war, famine, the Irish Troubles and the homeless had been published there. ‘He is a great photographer,’ writes Picton, ‘but his employment by The Sunday Times inhibits him.’ Picton advances an argument about the pictures’ presentation in a colour supplement surrounded by consumer advertising that became increasingly familiar. In essence, the issue is one of politics. What is the argument that disturbing news pictures are meant to convey? And what change is this voyeuristic photojournalism supposed to bring about? Picton contends that The Sunday Times’ true position in relation to these terrible events was one of resignation, that it accepted the outrages it delivered to the reader’s breakfast table ‘as part of an imperfect world’ that could not ultimately be ameliorated.

McCullin returned to this dilemma in another confessional interview, published in 1984 in Granta no. 14. What is his own political stance, he wonders? He takes the side of the underprivileged and would never say he was politically neutral, but he can’t decide whether he is on the Left or Right. He is bemused by the language of political theory and says he doesn’t vote. ‘I knew that my pictures had to have a message,’ he says. ‘But what message? I couldn’t have said – except, perhaps, that I wanted to break the hearts and spirits of secure people.’ He had seen people dying in the mud and he would force the distant viewer to contemplate this suffering. In 2009, though, in an interview in Aperture no. 195, McCullin admitted that he was ‘seriously doubtful’ such pictures made a difference and he conceded their potentially exploitative aspect: ‘We know we can be celebrated in photography.’

For critics of photojournalism as it was practised in the mid-twentieth century, this has long been the problem. ‘Documentary testifies, finally, to the bravery or (dare we name it?) the manipulativeness and savvy of the photographer, who entered a situation of physical danger, social restrictedness, human decay, or combinations of these and saved us the trouble,’ writes the artist Martha Rosler. In the end, the focus of the pictures becomes the photographer – ‘as hero’ – who gets famous for taking them and builds a career. McCullin always resisted the idea that his photographs were art rather than journalism. Yet he wanted to be a great photographer and his images are formally brilliant. In the midst of the ghastliest events, sheltering from enemy fire, and even when injured himself as a result of the huge risks he took, he had the eye and the instincts to produce perfectly balanced compositions.

After reviewing the arguments against this kind of photojournalism, it is salutary to return to some pictures. As an example, let’s take McCullin’s shot of a Vietnamese civilian in Hue being tormented by US Marines as a Viet Cong suspect before being released. The slight, bound, blindfolded man kneels in the dirt while three soldiers tower behind, peering down at him like an animal: an image of total dominance. This was first published in colour in The Sunday Times Magazine in March 1968 and the black and white version is shown in both the Aperture and Granta interviews, where it is the first image; it can also be seen in the monograph Don McCullin, reissued in 2015.

Don McCullin, A civilian tormented by US Marines as a Viet Cong suspect, Hue, 1968. © Don McCullin.

Top: Cover stories by Don McCullin for The Sunday Times Magazine, 1968-76. Subjects include Northern Ireland, Vietnam, Beirut, Cambodia, Bangladesh and Cuba. Source: The Times.

Would it be better for this picture not to have existed (lest the photographer profit from it)? Did its appearance in a colour supplement, where the photo-story was given twelve pages, and its subsequent place in our collective image-bank of the Vietnam war fatally compromise its ability to provide insight into the conflict? Is the content of the image vitiated by its aesthetic precision? My own answers are ‘no’. Notoriously, the UK’s Ministry of Defence later denied McCullin the chance to go to the Falklands. Those officials well understood the potential public impact of photographs. Photographers who report on wars are more restrictively supervised now. Rosler’s ‘saved us the trouble’ is far too dismissive. No matter how mixed their motivations, photographers such as McCullin bear witness, often at physical and mental cost, and it is the viewer’s responsibility to keep these discomfiting images in mind and think hard about what they show.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, Professor of Design and Visual Culture, University of Reading

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.