Winter 2003

The learning brand

Abstract covers give an identity to this ambitious book series. Critique by Rick Poynor

At a time when arguments about dumbing down continue to simmer, Oxford University Press’s Very Short Introductions show that it is possible to take the most serious topics and make them inviting and accessible to ordinary readers. The series, launched in the mid-1990s, covers every area of human knowledge and intellectual inquiry, from ancient philosophy to world music, from Russian literature to animal rights. The books are written by experts, usually academics, for anyone who requires a grounding in a subject. The 100th title appeared in June 2003 and dozens more are forthcoming. If you spent three years – the length of a first degree – absorbing the contents of these volumes, you would emerge a remarkably well informed person.

The decision to call the books Very Short Introductions was a masterstroke. It accepts that modern readers are pressed for time and that attention spans are perhaps shorter than they were. The unexpectedly informal ‘Very’ suggests that strenuous efforts have been made to focus each title on the essentials. Those who have attained mastery in a subject might be inclined to dismiss this as a marketing ploy, but it clearly works. The books are enticingly small, too – genuine pocket books – which make even the weightiest matters appear manageable.

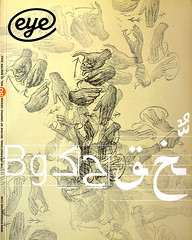

It’s the covers, though, redesigned in 2000, that give the books their special identity. Each one follows the same format. The words ‘A Very Short Introduction’ form a central axis, with the author’s name and title ranged above. The type size and style is consistent, though the title, set in Carol Twombly’s Lithos, inspired by early Greek inscriptional lettering, has to be reduced if a word is unusually long. The typeface’s contrasting character widths and sprightly line add to the informality. Every volume features a painting by Philip Atkins, a former designer at OUP, which wraps around the back cover and on to the flaps. The painting is divided into three horizontal bands. The largest, at the top, finishes just below the series title. Under this is a narrow strip, usually in a contrasting colour, and beneath this lies a broader band in a third colour.

From these simple, abstract devices Atkins obtains a great variety of moods. You only have to see a handful of the books to become fascinated by the seemingly limitless permutations. Cynthia Freeland’s Art Theory shows the elements in their least inflected form. The brushwork is smooth and the paint surface solid, with a small trace of white paper showing through, and the colours, mixed a little where they touch, are distinct. This is a tranquil image and many of the covers are like this. You are not encouraged by the colour choice or paint handling to view them as an interpretation of the theme.

In other cases the link is inescapable. Buddhism, one of the best-selling titles with sales of 26,000, evokes a mood of meditation with delicate brush strokes and glimpses of paper through watery veils of colour. On the cover of Terrorism, the ‘sky’ has turned a fiery red and the central strip is filled by dark clouds of paint clinging to the horizon. In a startling departure from the bright hues used for many titles, the heavy browns of Fascism portray a drab, colour-purged world in which every element merges with the mass. Poststructuralism presents the viewer with more of a conundrum. Here, again, the clear distinctions between colours are breaking down, while corrosive drips descend towards the title, further disrupting the cover’s usually stable horizontal structure.

This kind of design does not receive much attention as a rule – it’s insufficiently showy – but as a visual representation of a hugely ambitious publishing programme, it is superbly well judged. It expresses the series’ identity in a subtle, distinctive and memorable way. The books gain by being seen with other titles and, when they are gathered in a display, they radiate colour. The series might grow over the years to hundreds of volumes. Any image-led approach would run the risk of becoming dated or dull. Abstraction avoids the literalness of figurative illustration and the visual continuity embodies the publisher’s commitment to explore every branch of knowledge.

Only one complaint. After more than 100 titles, including books about architecture, linguistics and ethics, design has yet to receive a look-in. A volume by John Heskett, who specialises in industrial design, is in preparation.

Rick Poynor, writer, founder of Eye, London

First published in Eye no. 50 vol. 13 2003

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.