Autumn 2011

The list goes on

Umberto Eco’s book The Infinity of Lists is erudite, informative and beautifully crafted: a contemporary Wunderkammer. Critique by Rick Poynor

This summer I decided, very belatedly, to read Umberto Eco’s novel The Name of the Rose. Part way through I encountered an extraordinary list and it was clear that Eco, like many writers who use lists as a literary device, had taken great pleasure in constructing it. The narrator is imagining the wanderings of a fellow monk and all the dubious characters he must have encountered on the road: ‘vagrants fleeing from convents, relic-sellers, pardoners, soothsayers and fortunetellers, necromancers, healers, bogus alms-seekers, fornicators of every sort, corruptors of nuns and maidens by deception and violence, simulators of dropsy, epilepsy, hemorrhoids, gout, and sores, as well as melancholy madness.’

This lip-smacking parade of miscreants is just a fragment of a long, brilliantly imagined passage. Looking at a bibliography of Eco’s books, I found that in 2009 the Italian novelist and professor had published an entire volume about lists with the irresistible title The Infinity of Lists (Maclehose Press). I suspect many Eye readers may also have overlooked this hugely informative, diverting and beautifully designed book.

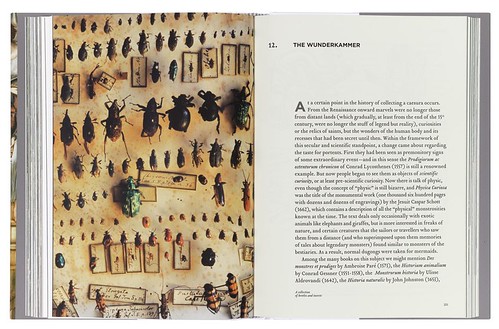

Chapter opening of ‘The Wunderkammer’ with an updated collection of beetles.

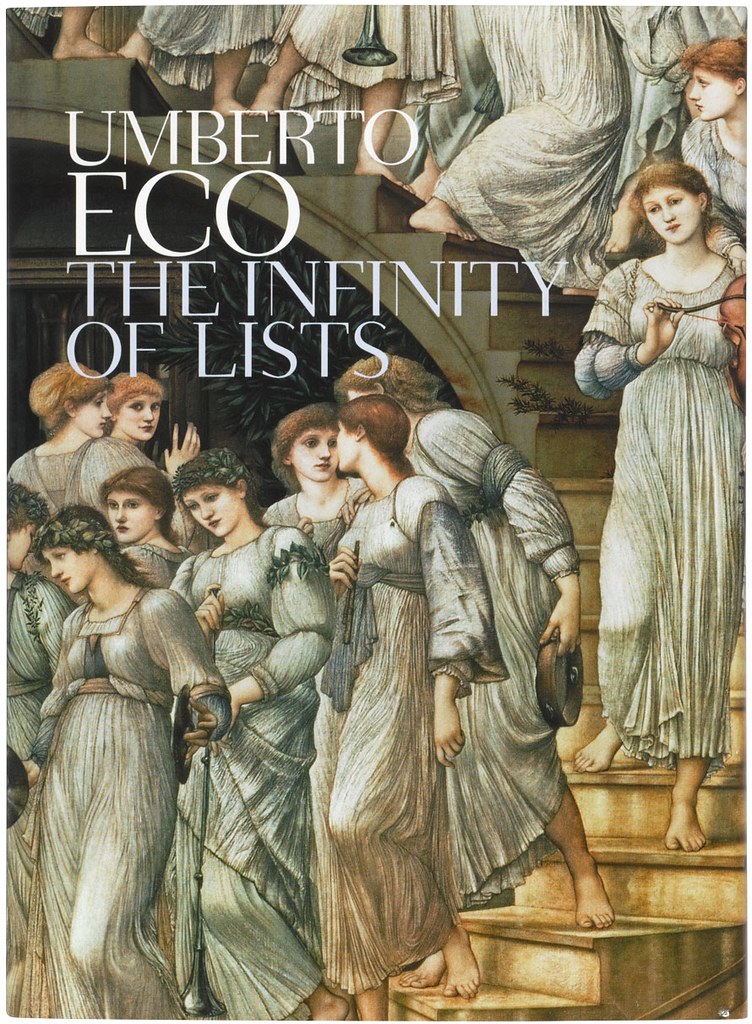

Top: The cover of Umberto Eco’s The Infinity of Lists, designed by Polystudio:a detail of The Golden Stairs by Edward Burne-Jones, 1880.

The subject of lists has come up before in these pages. In 2003, Alice Twemlow wrote an excellent article about the ubiquity of the list in contemporary publishing and visual culture (Eye no. 47 vol. 12). She noted that the list was being used as a way of generating content without needing to say anything definite about it, though some designers were managing to find clever uses for the device. In the course of her discussion, Twemlow mentions a number of historical precedents, including a list made by Homer in the Iliad of captains and their ships, and a categorically confused list of animals referred to in an essay by Jorge Luis Borges that supposedly appears in a ‘certain Chinese encyclopedia’.

Both of these extracts appear in The Infinity of Lists at either end of a survey that amasses an overflowing trove of examples from literature and art. (I’m not suggesting Eco has seen Twemlow’s essay; he makes some penetrating observations about contemporary lists, but this isn’t his focus.) With taxonomical relish, he structures the book as a series of short introductions to different kinds of list-making: the visual list, exchanges between lists and form, the rhetoric of enumeration, the Wunderkammer, coherent excess, exchanges between practical and poetic lists, and so on.

Each of these playfully erudite overviews culminates in a series of exemplary texts, which range from lists of names of angels and demons, and litanies of saints, to a famously outrageous and hilarious section from Rabelais’s Gargantua and Pantagruel (1532-34) about ways to wipe one’s behind (Rabelais emerges as an all-time great literary list-maker; see also his list of imaginary books). There is a scene from Zola’s Abbé Mouret’s Transgression (1875) as fantastically overwrought as it is tedious, where every flower in a garden is itemised during a lovers’ tryst. Eco, a self-described ‘aficionado of lists in all my novels’, even permits himself to include the passage from The Name of the Rose.

Many of these examples convey what he variously calls ‘pure love of iteration’, ‘a mad kind of accumulation’ and ‘the dizzying voraciousness of the list’. The same sensation of vertigo can be experienced in the many paintings and graphic works that illustrate the book’s themes. The suggestion, here, is that the burgeoning imagery captured within a picture’s frame continues beyond its edge and is potentially without limit – the list always implies there could be so much more than we are being shown. These attempts to impose order, Eco said in an interview, are a tool for making infinity comprehensible, and the endless list is also a means of fending off thoughts of mortality. The survey’s visual editing, too, is exuberantly eclectic: Albrecht Altdorfer, Albrecht Dürer, Domenico Remps, James Ensor, Ernst Haeckel, Gino Severini, Hannah Höch, Yves Tanguy, Arman, Daniel Spoerri – for want of space, a list will have to do.

In its Italian designers, Polystudio, this life-affirming feast of a book found the form-makers it deserved. This is the kind of design that is so finely measured that one barely thinks of it as being design at all. The type is a pleasure to read – the style might be called classical modern – and the pictures are placed with an acute sensitivity to their value as documents and their aesthetic power as images. The designers appear fully in tune with the author’s intentions, with the book’s boundless subject and with the reader’s ease. I can’t praise The Infinity of Lists more highly than to say that it, too, can be viewed as a Wunderkammer.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, London

First published in Eye no.81 vol.21 2011

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.