Winter 2016

Traces of a drifter

Camera in hand, Harry Pearce dives into the urban underbelly in search of the unfathomable. Photo Critique by Rick Poynor

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor, written exclusively for Eye magazine.

Is there something about graphic design as an activity and a way of seeing that predisposes designers who take photographs to focus on objects and surfaces rather than human subjects? ‘The absence of people is intentional,’ writes Harry Pearce, a partner at Pentagram, in Eating with the Eyes, a collection of his photographs published by Unit Editions. Pearce is referring to a picture of a wall dotted with flakes of torn paper and clumps of string, but the principle applies to every image in the book. In 1967, Herbert Spencer, also a designer and photographer, titled a similar collection of people-less scenes Traces of Man. This is what Pearce has recorded, traces of unseen actors whose attentions, both deliberate and accidental, shaped these wondrous and frequently ‘unfathomable’ objects and textures: rust, flaking paint, pipes, bricks, sheets and empty chairs.

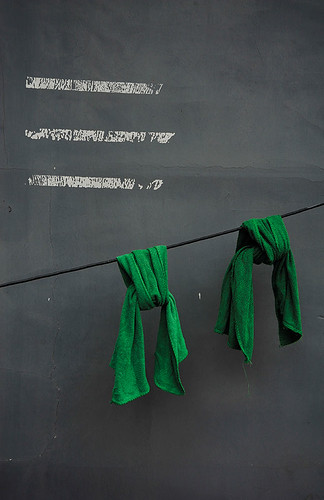

Napoli.

Top: London.

Photographs by Harry Pearce, from Eating with the Eyes, 2015.

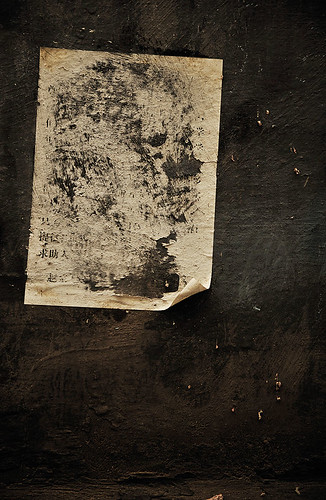

Beijing.

A few pictures show scenes in London, but Pearce takes the photographs mainly on his travels overseas, in Havana, Jerusalem, Delhi, Mumbai and Beijing. He ventures into obscure private squares shrouded in gloom in Naples and lurks under massive concrete flyovers in Hong Kong.

He has spent months, he writes, ‘lost in the underbelly and back streets of cities’. The excitement he feels on these solo trips into cultures he barely knows is often mixed with anxiety; these places are not always safe for interlopers. ‘The deeper you go … the more you take your life in your hands.’

Pearce describes his expeditions as a kind of drifting and he belongs to a self-conscious fraternity (and sisterhood) of hyper-attentive city wanderers that began with the nineteenth-century flâneurs and leads to the psychogeographical dérive of the Situationists. The Surrealists, too, criss-crossed the city on foot in pursuit of signs and wonders, and Pearce makes a number of references to the inspiration he drew from his discovery of Surrealism as a teenager. He was enraptured by the idea of André Breton and others taking nocturnal rambles in the streets of Paris, their senses alert for chance encounters. Breton’s writing honed his appreciation of the symbiotic relationship between the realms of the conscious and unconscious and he characterises his daydream-like state, as he forages for pictures, as being on the threshold between interior and exterior realities.

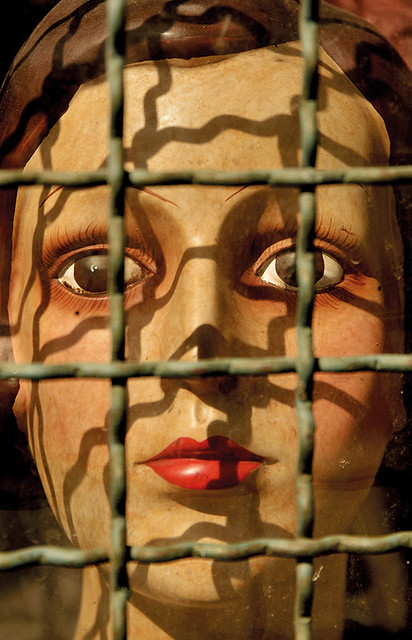

Oporto.

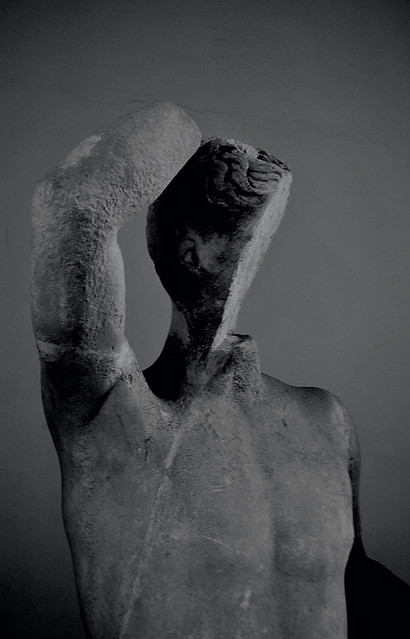

Napoli.

He compares an old door pinned with two deflated balloons to a Surrealist object and describes a broken chair like an insect as an ‘accidental unconscious sculpture’. The mannequin may be a stock figure from Surrealist central casting, but in the hillside streets of Oporto, in Portugal, Pearce discovers a red-lipped beauty, its melancholy visage pressed against a confining grill. Some of these chance constructions – two green scarves on a wire meeting three tape marks on a wall – have the air of being secret messages composed in a code that no amount of pondering will decipher. Pearce’s most eloquently poetic pictures are often severely reductive in colour and form: a pile of flattened flour sacks in Shanghai; a male nude statue with its face missing, as if cut off by a saw; the remnants of a pasted poster on a dark wall, where the abrasions conjure a phantom portrait. For both image-hunter and viewer, scenes like this can seem to vibrate with enigmatic import. ‘For me,’ notes Pearce, ‘they are views into the deep nature of things.’

Not all the pictures have this gravitas, and some betray a lighter, less exacting eye. In Beijing, Pearce notices that an upturned mop with a green brush looks like a small tree – a simple visual pun. It amuses him that a painter in the London Underground has half crossed out ‘mind’ (the gap) on the platform with a yellow line. He can’t resist pointing out in a caption that the labial folds of a Bedouin tent are ‘gently erotic’, even though the image has amply made the case. He gives every picture a caption, which can be useful when they provide information, but often they merely repeat what we can see – ‘Painted wood, concrete and the accidental flick of the brush’ – dampening the mood of mystery. The explanations are presumably there to add visual interest to the pages, but the images don’t need them. What I wanted were some dates. The folded pages are also a barrier to full immersion. The book has a steep-sided gutter when open and won’t lie flat.

‘There are no accidents,’ Pearce writes in the foreword, ‘only ideas trying to find us.’ Here, again, we glimpse the perhaps inevitable tension between the roles of designer and photographer, because this is not what the most arresting pictures have shown. As he writes in the next sentence, what the images actually reveal is the ‘wonder in the overlooked’. We might use visual discoveries like these as prompts for design, but this

would be to skip over their revelatory power as instances of what the Surrealists called le merveilleux and get back to business. There are some remarkable photographs jostling for space with more ordinary ones. I would like to see Pearce be tougher in his visual editing and even more purist.

Beijing.

Havana.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, London

First published in Eye no. 93 vol. 24, 2017

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue. You can see what Eye 93 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.