Wednesday, 10:00am

18 March 2020

Whiteness made strange

Broomberg & Chanarin

Michelle Dizon and Viet Le

Buck Ellison

Ken Gonzales-Day

Hank Willis Thomas

Photography

Critique / Photography

A brave, if flawed book of artists’ photographs addresses racism through the lens of white privilege. Photo Critique by Rick Poynor

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor, written exclusively for Eye magazine.

No decent white person wants to be regarded as racist and the easy liberal assumption has been that if you are not doing or saying racist things and you deplore those who do, then you are in the clear. That complacency has been challenged repeatedly in recent years with the accusation that racism is structurally inscribed deep within all kinds of institutions created by a white-dominated society. By doing nothing substantial to change these institutions and continuing to accrue power and benefit from their persistence, white people are implicated in racism whether they regard themselves as non-racist or not.

From a non-white perspective, the pervasiveness of racism goes even deeper than that. Whiteness itself is the problem – not the colour of a person’s skin, but the mentality that comes with being white. For white people this is mostly unconscious: being white and thinking like a white person are just the natural way to be. Whiteness is ‘normal’ and taken for granted and every other skin colour is tacitly perceived as a divergence from this ‘norm’. Awakening to how things really are can be shattering. George Yancy, an African-American professor of philosophy, describes a student’s struggle in class to accept these insights. ‘This is terrifying!’ she said, as she contemplated the implications for her white identity. ‘It was more than seeing her whiteness as strange,’ says Yancy, ‘but seeing her whiteness as terrifying in its unethical weight, toxicity, and destructive consequences for Black people and people of colour.’

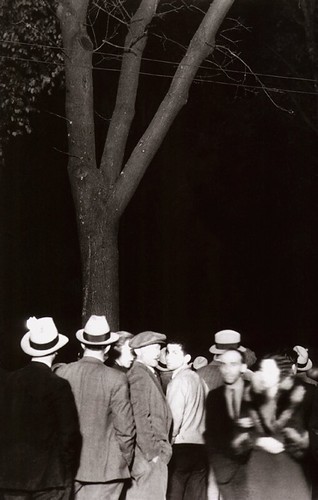

Ken Gonzales-Day, East First Street #2 (St. James Park), from the series ‘Erased Lynchings’, 2013.

Top. Hank Willis Thomas, Wipe Away the Years, 1932/2015, from the series ‘Unbranded: A Century of White Women, 1915-2015’.

Yancy is speaking in an interview with Daniel C. Blight, editor of The Image of Whiteness: Contemporary Photography and Racialization (SPBH Editions / Art on the Underground). It is a challenging book and a brave one. ‘I am obliged to state clearly and unequivocally that as a white man, I am implicated by and in my own arguments,’ writes Blight, who teaches at the University of Brighton. His task, which he suggests every ‘not racist’ white person must share, is to untie the knot of this internalised whiteness and racism: ‘White people must remove whiteness from the centre of humanity.’ In a quotation used by Blight as an epigraph, Yancy asserts that the ‘death of whiteness’ would ultimately create a better life for both black and white people.

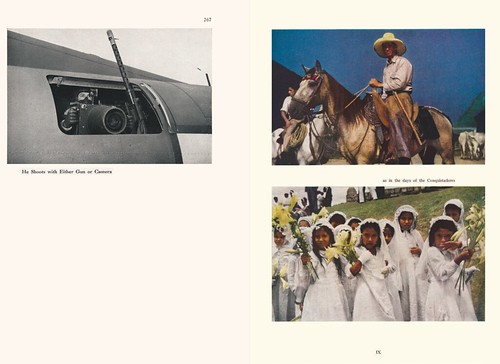

Michelle Dizon and Viet Le, White Gaze (book spread), 2018.

The arguments advanced with great eloquence by Blight, Yancy and others make this book enlightening reading and this establishes high expectations that the photographs – made by artists – will match and extend these revelations. As Blight points out, citing the history of anthropological photography, the photographic image was, from the outset, a central tool in the imperialistic representation of people of colour and the assertion of whiteness. Local photographic practices, which revealed indigenous people’s views of themselves, were invariably overshadowed and this cultural domination continued deep into the twentieth century.

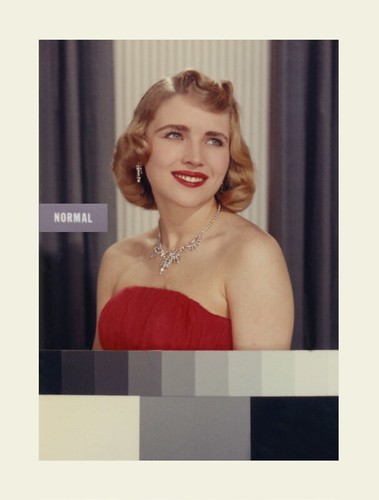

Broomberg & Chanarin, Shirley 1, from the series ‘How to Photograph the Details of a Dark Horse in Low Light’, 2012.

It would be highly revealing to revisit the history of photography, and particularly its documentary uses, from this critical perspective, but that is not Blight’s purpose here. He comes closest when he shows Broomberg & Chanarin’s appropriated Kodak colour cards from the 1960s, Shirley 1 and Shirley 3, where the resplendently white photographic models are labelled ‘normal’ – in colour terms – on the image. Conceptual artist Hank Willis Thomas also has an eye for the unintentional meanings to be mined from old pictures, from which he eradicates the original advertising copy lines. A bikini-clad white woman swings through a jungle-like setting on a vine in the manner of a female Tarzan, radiating a colonial sense of ease and entitlement in an environment that is manifestly not her own.

This is a kind of détournement, as the Situationists termed it, a negation and redirection of the image, but how far is it genuinely illuminating to go? In an advertising photo from the 1930s, an unhappy looking woman contemplates her face in a mirror (top). For Yancy, this piece, also by Thomas, is about ‘rendering whiteness strange … it is as if the white woman really sees herself differently for the first time, sees what she was never meant to see as strange, but as normative.’ Blight assumes the original ad was for face cream. In fact, it was for Johnson’s floor wax, and the copy line above the image supplied her thoughts in quotation marks: ‘beginning to look like an old scrubwoman’. The model is pretending to be sick of scrubbing the floor and the ad – available as a stock photo from Alamy – presents the cleaning solution. While the decontextualised image can be made to symbolise the argument about whiteness, it was the product of pure commercial artifice, not a scene of existential crisis. In any case, people of every skin colour look into mirrors for every shade of reason.

Buck Ellison, The Prince Children, Holland, Michigan, 2019.

Other images are even more roundabout in the way they express the book’s four themes: the white body, the white gaze, borders of whiteness and symbols of whiteness, none of which are clearly attached to the pictures. This raises the usual questions about the efficacy of art practice as a means of disseminating social critique and connecting with the ordinary viewers who don’t follow art that Blight presumably wants to persuade and change.

Placed in the loaded context of the book and used on the cover, Buck Ellison’s photograph The Prince Children, Holland, Michigan might seem almost sinister: look at these supercilious white rich kids embracing their place at the social apex as a matter of birthright. But it would be possible to take equally assured photographs of wealthy family groups anywhere on the planet. If this picture were to be shown to white viewers without explanation, ‘whiteness’ would be unlikely to arise as an issue. Even knowing that the scene is entirely staged and that this is not a real family would not be enough to prompt this self-critique since, by definition, the subjects’ sense of entitled whiteness will be taken as normal. Of course, people of colour would read the image differently because they know this already.

I cannot see that ambiguity helps very much here, especially when the change of awareness demanded is so colossal. An issue this important to society requires careful argument, which the book presents, and more direct and even didactic styles of visual exposure and address.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, Professor of Design and Visual Culture, University of Reading

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.