Wednesday, 11:00am

24 January 2018

Witness of the moment

A book of informal interviews with Henri Cartier-Bresson is testament to a great photographer’s intuitive eye. Photo Critique by Rick Poynor

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor, written exclusively for Eyemagazine.com

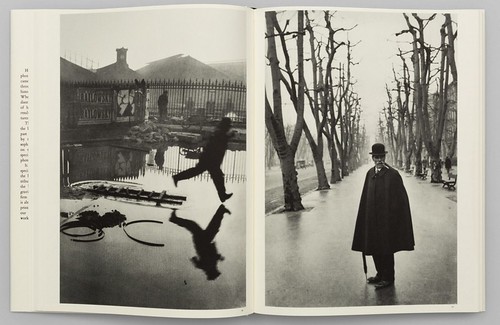

The kind of photography that Henri Cartier-Bresson excelled at is not currently in fashion. For the photographer as would-be artist, the practice has become conceptualised. The 21st-century photograph of note is not something found in the world, a fleeting moment captured with immaculate instinct and timing, but an image that has been premeditated and meticulously fabricated to embody an agenda. Cartier-Bresson will forever be identified with the English title of his book, The Decisive Moment (1952), though his American publisher suggested the phrase, and he didn’t regard it as an adequate summary of his methods. Photographic discourse now tends to view the decisive moment with some suspicion and some say Cartier-Bresson’s perfectly resolved compositions were entirely too ‘decisive’.

Spread from Cartier-Bresson’s The Decisive Moment.

Top: Cover for Henri Cartier-Bresson: Interviews and Conversations 1951-1998, edited by Clément Chéroux and Julie Jones (Aperture).

For those inclined to view this appraisal with their own measure of scepticism, Aperture’s Henri Cartier-Bresson: Interviews and Conversations 1951-1998, edited by Clément Chéroux and Julie Jones, is a timely arrival. The book brings together English translations of twelve encounters, from the height of Cartier-Bresson’s professional success to his later years when he had largely retired from photography and was preoccupied with drawing. Born in 1908, he readily acknowledges that he was shaped by his era (as everyone must be) and it is a sign of his integrity – a quality he valued most in both men and women – that he held to his guiding principles across the decades.

He was resolutely opposed to contrivance in a picture – ‘reality is so much richer!’ Photographers, he says, are ‘witnesses of the transitory’. He describes himself as being in a constant state of nervous readiness and repeatedly stresses the importance of intuition, the other quality he most values. ‘Photography is made in the here and now,’ he stated in 1961. ‘You have no right to manipulate or cheat.’ The photographer must think before taking a picture and again afterwards, but not in the act of taking it, when intuition and instinct are everything: ‘each time a picture is planned, elaborated, it becomes stuck in clichés.’ The photograph’s full implications and meaning were usually not apparent in the second it was snatched and would only emerge later on reflection.

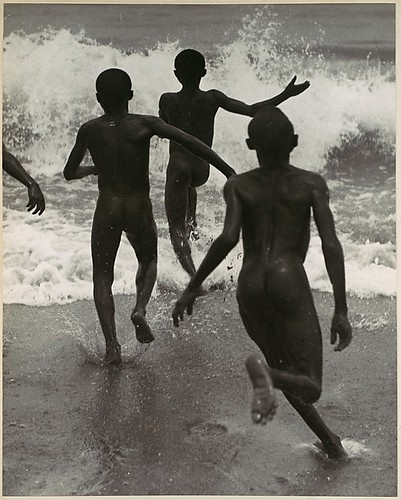

Cartier-Bresson studied painting in his youth and turned to photography in his mid-twenties after acquiring a 35mm Leica. Several times he cites a shot by the Hungarian photographer Martin Munkácsi of boys on a beach running into the surf as an example of a flawlessly composed image of movement. The earliest pictures Cartier-Bresson took in the 1930s show his exceptional facility for composition. He notes how just a few millimetres’ adjustment in viewpoint can make the difference between a picture that succeeds or fails. He always resisted the cropping of his photos because if an image had been properly composed, then everything was in the right place and nothing could be taken away without damaging it. He favoured an even light and acknowledged the ‘classicism’ of his pictures.

Martin Munkácsi, Liberia, 1931. Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987. © Joan Munkácsi, courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery.

Photography as a practice was of little interest to him and he thought there was too much talk about it. He was against schools of photography – ‘Reportage techniques can be learned very quickly.’ The point was to engage impulsively with life, to look closely, and taking pictures gave him a licence to travel and to ‘nose around’. He was a libertarian, with an anarchist’s mistrust of power, and the Surrealists’ philosophy, spontaneity and rebelliousness had a lasting influence.

He wasn’t a member of the Surrealist group, but he attended their meetings and mentions his admiration for founder André Breton several times. Breton included a picture by Cartier-Bresson of Spanish children playing among ruins in his book Mad Love (1937). He tended to keep quiet about his debt to Surrealism after Robert Capa – fellow founder of the Magnum Photos co-operative in 1947 – warned him that it would put off potential commissioners. Looking back, he describes a life of ‘hard pleasure’ – using a doctor friend’s phrase – rather than conventionally taxing work. Never fully a photojournalist in attitude, despite all the commissions from magazines, his métier was the photographic essay focusing on the life and texture of a place.

The interviews and conversations make for engrossing reading. Cartier-Bresson lived life to the full (he died in 2004) and he comes across as simultaneously guarded and garrulous, wilful and reflective, confident of his achievement and attractively self-effacing – ‘It’s great to be famous, as long as you remain unknown.’ With its black uncoated cover and flaps, the book is smooth to the touch and snug in the hand, like the kind of notebook travellers might slip in a pocket to record the stories behind their pictures and other impressions. Brian Berding’s typography is both literary in tone and approachably informal. This nicely judged collection of insights is a testament to the experience-embracing openness and masterful eye of one of the great twentieth-century photo-adventurers.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, Professor of Design and Visual Culture, University of Reading

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.