Winter 1991

After the wall

Unlimited horizons? East Berlin design group Grappa come to terms with the new Germany

While the cultural ramifications of German reunification remain uncharted, the impact of Die Wende on graphic design is already apparent in Berlin. Die Wende (the turning point) is the term used by East Berliners when referring to the collapse of the Wall and its repercussions. In East Berlin, Die Wende has created the conditions for an emerging design hothouse. Exposure to the west will inevitably place the work of Grappa and other East German design groups in a pivotal position on the redrawn map of European design.

The current situation in East Berlin is one of creative energy and optimism. It’s DIY – the phenomenon of young designers getting together, finding premises, doing them up and launching their own design groups. Lack of business skills and experience is remedied by Praktikums (work experience) of two or three months undertaken in the west, in Stuttgart, Düsseldorf and West Berlin.

The lack of design groups posed East German designers with a choice: work in the west or work for themselves. Rather than being absorbed by western design companies, some eastern designers have stayed where they are most needed. There is a market opening up, and they have so far been competing successfully with western design groups. Clearly, there is no shortage of motivation and resourcefulness. The excellent typographic education gained at colleges such as Schöneweide is of interest to western designers and clients, and although standards vary, they are usually high.

The process is not without its setbacks, however. Designers have had to make major adjustments from a comfortable position in terms of guaranteed work and pay. There is the shock of new financial responsibilities, such as getting a loan. Eastern clients can be time-consuming; hours can be spent explaining benefits which would be familiar to a western client, or wasted on someone, who despite an important new title such as ‘marketing manager’, turns out not to be a decision-maker. Eastern designers are also labouring against prejudice from the west. Western clients have to be reassured, so appearances, and especially computers, assume an extra level of importance. The lack of technology in the east before Die Wende (which some regard as a benefit in their design education) has been speedily remedied in commercial practice. Improved print production, together with Macintoshes, have revolutionised graphic design in East Berlin.

Among these design groups Grappa holds an exemplary position. Founded in March 1989, they have successfully negotiated the Die Wende period. But how was it possible to establish a design group in the repressive regime of the GDR? ‘You get the idea and you do it,’ says Grappa’s Andreas Trogisch. For most designers, however, there was little motivation to form a group when one could get work easily as an individual, and suitably sized premises were difficult to find.

A sense of commonality, of working together to realise aesthetic and social ideals, has held the group together. Another reason for their smooth transition is the continuity of clients such as the Bauhaus Dessau, an important cultural icon to have retained. But not all of the clients from the GDR have survived; the giant monopolistic cultural agencies such as the Mode Institut, the Kunstler Agentur and DEWAG, the state agency for distribution of graphic design commissions, have been dismantled and other clients simply have no money.

Grappa have a reputation for high moral principles and have always been choosy about their clients. They once turned down an identity for a new youth production on the GDR television station. ‘It was a question of principle not to work for TV that was totally infiltrated by politics. That’s why we didn’t design journals in the GDR.’ These were official state journals such as Form und Zweck for design and Film und Fernsehen for film and TV. ‘To change the layout you have to change the whole concept,’ says Trogisch: form and content are inextricably linked. Now independent, these journals desperately need redesigning to compete with the west, and Grappa have taken on the job. How do their moral and political principles influence their design today? According to Daniela Haufe: ‘Society is better, but there are still things to object to.’ Grappa remain in opposition.

They are able to do this partly because most of their work is for the culture industry. A growing number of their clients are from the west, and Grappa were recently commissioned by the West Berlin district of Neukölln to design their cultural events programmes, and by the IDZ (the international design centre in West Berlin) to design their annual report.

The first thing one notices about Grappa’s work is that it doesn’t look like the German design we know. It is hard to place – Emigre fonts combined with a Dutch quality and sense of play. Many of Grappa’s eastern clients specify very low budgets, and consequently the majority of the work is two-colour with low-grade papers. A recent edition of Form und Zweck demonstrates how working with a tight budget can produce a novel, creative solution. The single-colour pages are left untrimmed in order to save the print finishing costs. This creates a useful set of pockets in which to insert loose full-colour illustrations to the text – another cost-saving exercise. The reader is tacitly invited to slice open the pages and reveal the spreads of the magazine as well as the contents of the pockets.

Another feature of Grappa’s designs is the intelligent combination of design sensibility with new technology. The group have a characteristically serious and considered response to computers. ‘We live with them,’ says Trogisch. ‘Our work is partly inspired by them. A computer may inspire you not by its possibilities, but by its limitations; limitations are its characteristics and you can play with them.’

Attitudes to Die Wende vary between six members of the group. For some, focus is on continuity of intention and personality. ‘“The wall came down and I am a new person!” This is rubbish,’ says Daniela Haufe. These members see no change in aesthetics, but acknowledge that new technology and new print techniques have altered the work. The recent anti-war poster, a free project made possible by good relations with their printer, is a pertinent example. It resembles the traditional political poster using photomontage, common in the GDR, but with the use of distinctive bitmapped type. Grappa also bring with them a complex set of cultural and historical influences, as well as a design education based on traditional skills and aesthetic considerations. They are able to hand-set metal type and it is interesting to speculate on where this collision of technologies will lead.

Other members of the group foresee a ‘breaking point’ when Grappa’s designs will change because circumstances are no longer the same. ‘Different clients, different technologies, different aesthetic backgrounds, different economic background – even if I’m the same person as before, my surroundings have totally changed and my work will change,’ says Trogisch. But the impact of Die Wende on graphic design will surely not reside solely in the realm of technology and economics – what of culture? If, as Trogisch asserts, the transformation in conditions does lead to a transformation in the work, the crucial questions will be: is it a positive change and can a new identity emerge unifying the best of east and west?

The east/west debate is topical, yet most of the design press ignores East German graphic design. Why the conspiracy of silence? ‘There is a tension in the city, but it’s a productive one,’ says Dieter Fehsecke. The situation is understood by both sides, although nobody wants to talk about it. But money can talk very loudly. The price is right in East Berlin! For western clients the standard of excellence and personal integrity will be an added bonus.

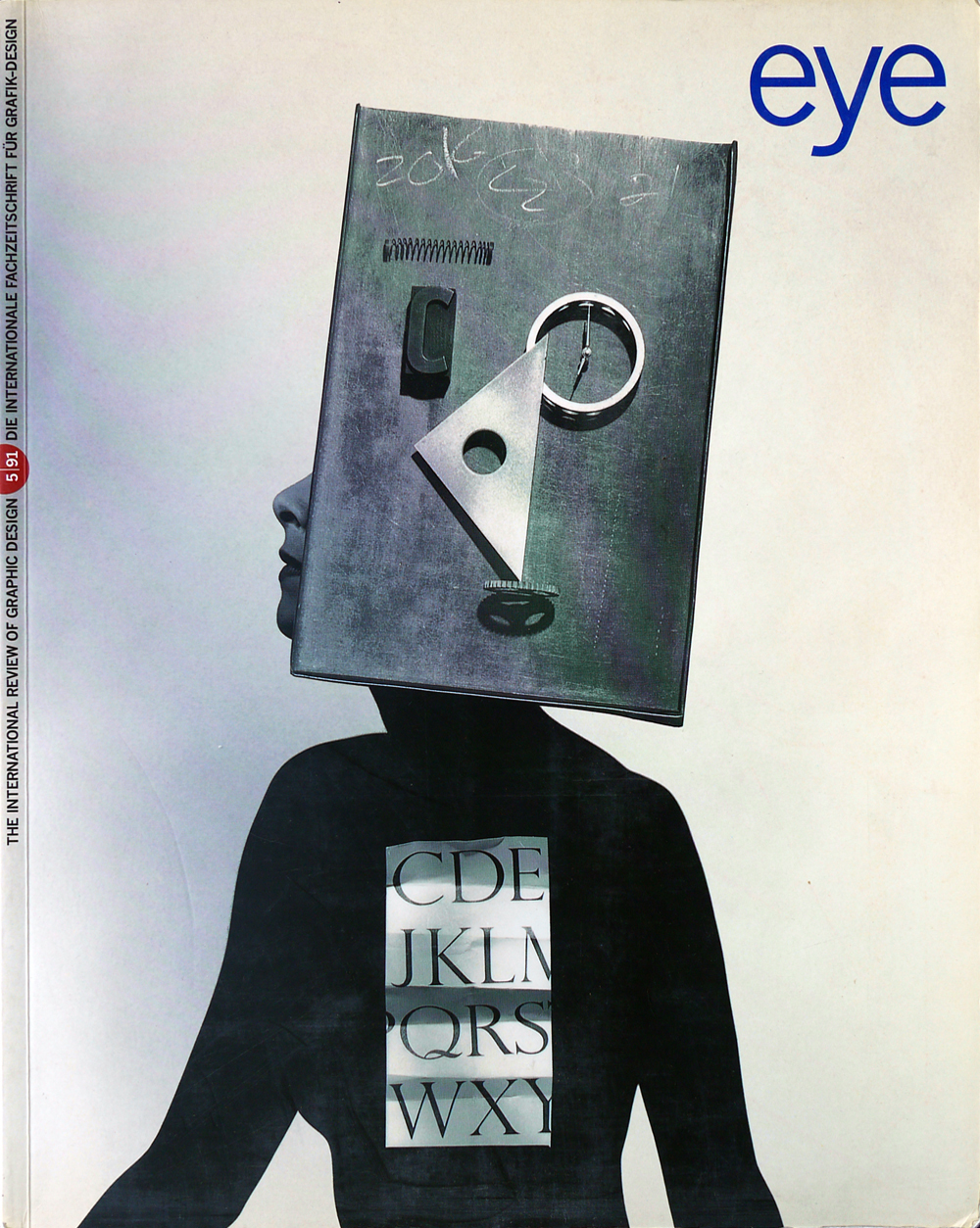

First published in Eye no. 5 vol. 2, 1991

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.