Summer 2016

Ambition and illustration

Alan Male welcomes a return to the ‘polymath principle’, the idea that an illustrator should engage with their subject matter at a deeper, more authorial level

The student illustrator is often under pressure to ‘break new ground’ and push the boundaries of the subject. This usually means the production of fashionable or ‘innovative’ mark-making without concern for content or message. But innovation is never just about visual language. Even the most traditional styles can shock audiences into taking note of contentious arguments; deliver groundbreaking new knowledge; and send any product into a realm of fantasy that will appeal to potential buyers.

Clients and media platforms increasingly require practitioners to have an individual and critical voice. They need them to be challenging, provocative at times, and to use their knowledge base to take ideas and move them into exciting realms of influence, confronting and contradicting the wider world of culture and communications.

Take, for example, work as different as Gwen Turner’s graphic novel series Domestic Bliss, Olivier Kugler’s reportage of Syrian refugees for Medecins San Frontières or the political cartoons of Martin Rowson, who claims to provide ‘an oasis of anarchy in the topography of newspapers’.

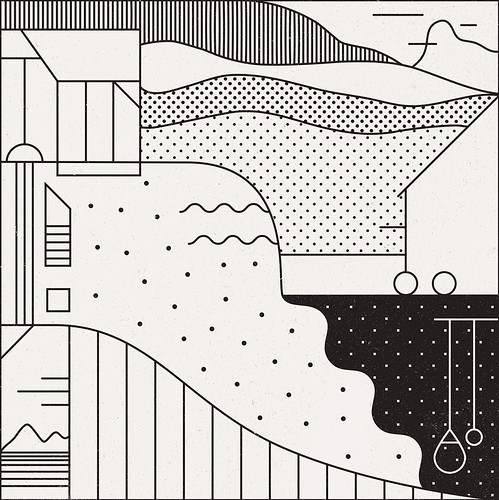

Mapping Eigg, a research project by David Lemm, 2015. The essence of this work is couched in exploratory cartography, the subject being the Scottish island of Eigg.

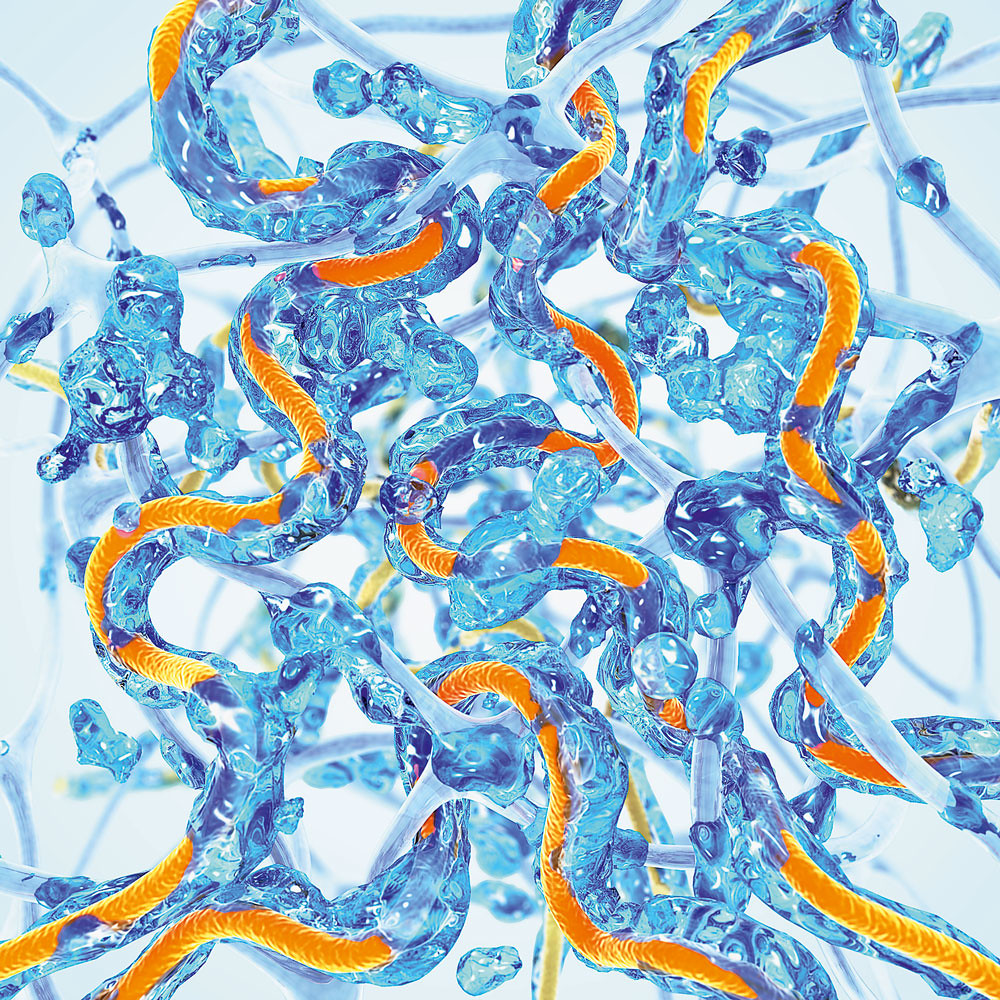

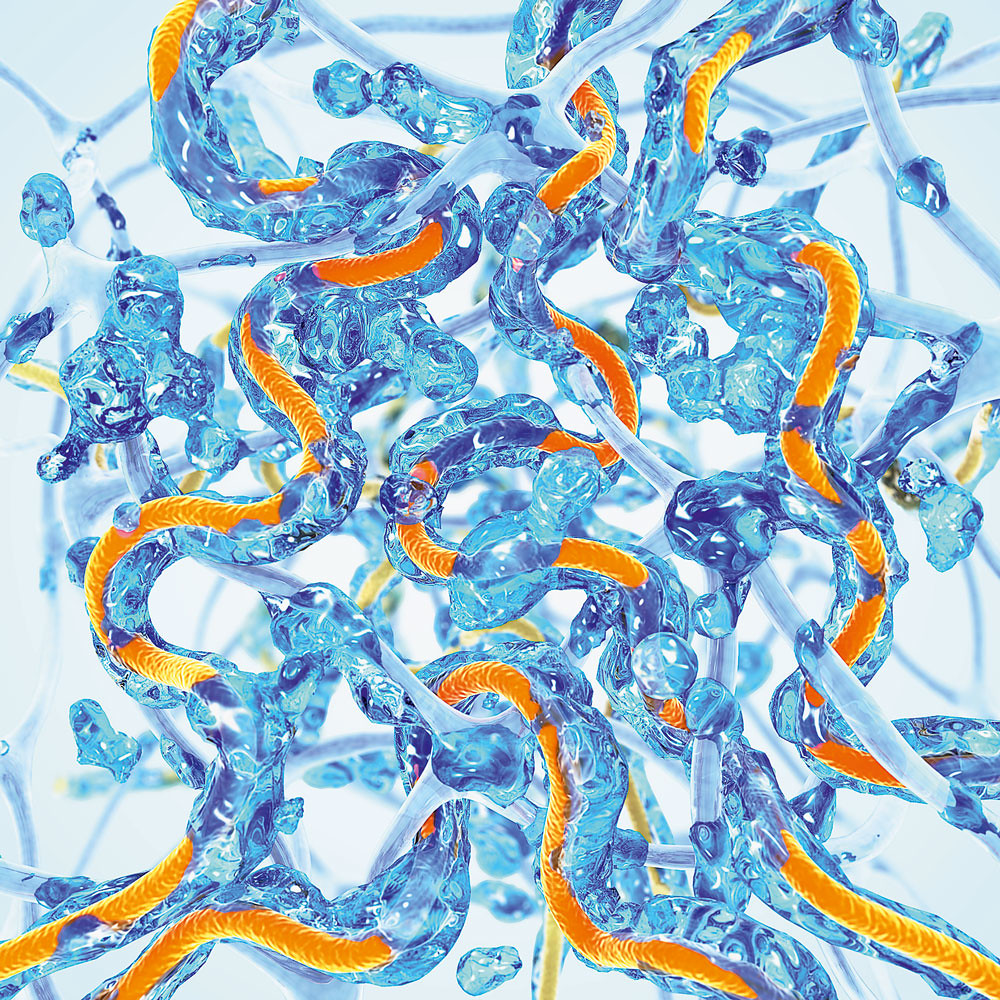

Top: A scientific illustration by Arran Lewis made to convey new knowledge regarding cellular micro-research about the lens of an eye, 2013.

It is the persuasive, informative and authorial power of applied illustration imagery, the strength and originality of its messages and its accessibility via global publication and broadcast media that defines its true reason for being.

The traditional five contexts of visual communication practice are knowledge exchange; commentary; fiction and creative expression; persuasion; and identity.

If new graduates are to enter the profession well prepared, they need an educational experience that encourages acquisition of specific, transferable skills that are not only practical, but intellectual and knowledge-based: the command of written and oral language, presentation and research. Such illustrators (and designers) need to be all-rounders, multidisciplinary, thirsty for knowledge. They need to be people of great and varied learning, with broad knowledge and skills. In other words, they must learn to become polymaths.

Learning from Leonardo

The separation of art and design from other disciplines is a recent one. One of the most famous polymaths, Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), plays a significant role in our early understanding of science and technology as well as art history. Knowledge was the driving force behind the work being produced by Renaissance artists. Anatomy, astronomy, mathematics and architecture underpinned the imagery being produced; in many cases it was the reason for its production. The scientific propositions and discoveries of Da Vinci’s time were not just described in textual form – they were illustrated. The ideas within were externalised through drawing.

Similarly, the nineteenth-century polymath had a broad, deep and detailed knowledge of all areas of culture, science and human endeavour. Practically every subject known to humankind was subjected to intense scrutiny and research by the engravers of the Victorian age.

So what type of work exemplifies this approach for a polymath-driven practice today? In what contexts can an illustrator develop such a practice? Happily, there are many areas that need the skills and insights of illustrators, including advertising, retail, publishing, education and e-learning, documentaries and information design for TV, theatrical and digital broadcast, exhibitions and museum archives (both physical and digital).

So if we agree that a principal aspect of interdisciplinary practice is authorship, how can an emerging illustrator or graphic artist gain the status of author?

Some achieve this through work; others come to the field with a background or training in areas such as archaeology, botany, biology, zoology and so on. They may have undertaken undergraduate or postgraduate degrees in other subjects before going on a design or illustration course. Or they may have been handed a brief that required rapid research into specialist content. Such encounters can lead to the practitioner assuming authority regarding themes and subjects in a way that may later qualify them as an ‘expert’.

Illustration and writing are not just adjacent; the two practices are deeply intertwined. For example: journalism and commentary = editorial imagery; literature and other forms of fiction = narrative imagery; academic, documentary and technical authorship = information and knowledge-based imagery; copywriting and media literature = advertising and corporate imagery.

The foregoing examples clearly require interdisciplinary practice. They point to where creative expertise or deep specialist knowledge can initiate some wide-ranging, ‘hyphenated’ job descriptions such as illustrator-scientist, illustrator-author, journalist, historian, musician, academic, researcher or scriptwriter, etc.

This is not a lofty, impossible ideal. There are many people, from recent graduates to well known artists, whose practice exemplifies what I call the ‘polymath principle’ in a wide range of contexts. For example Jemma Westing, working in-house at Dorling Kindersley, conceived and saw through in its entirety Optical Illusions, an interactive book aimed at junior age (5-9 years) children. She was subsequently promoted to project art editor.

Arran Lewis, who supplemented his illustration degree with extra-curricula study at the Peninsular Medical School in Cornwall, is now the Director of Ecorche Medical Anatomical Scientific 3D Illustration, whose clients include the Wellcome Trust and the BBC.

David Lemm’s research project Mapping Eigg (in conjunction with Edinburgh University) is an innovative and original approach for discovering how maps can be both material artefacts and sources of new knowledge and information.

Emma Yarlett, who graduated in 2011, has established a career as a creator of children’s literature, writing and illustrating Sidney, Stella and the Moon (2013), an unequivocal example of ‘authorship’ that she continues alongside commercial commissions such as typographic design, editorials, packaging and publishing.

As educators we need to adopt a holistic and nondiscriminatory overview of the whole discipline, developing a deep understanding and application of all its contexts and cultural applications. It is essential to transcend a surface engagement with just contemporary trends in visual language and make one’s practice say and do something mature and relevant. A meaningful approach is to be evaluative and enquiring, to have a voice and to engage in debate both nationally and internationally. The idea of illustrators and practitioner-educators discarding the role of being just artwork renderers, operating to a prescribed and directed brief so as to assume authority and ownership over content and subject matter takes on an alternative meaning. Illustration practice becomes holistic and acquires gravitas because it develops broadly, with parameters that extend far beyond the remit of commercial instruction. It becomes a vocation for deep learning facilitating opinion and fresh insights regarding one’s own practice and that of others. The driving force behind the need to do this will be informed by illustrators’ intellectual and creative potential – the ambition and desire to extend and to challenge their abilities.

A sea change – not only in the United Kingdon but worldwide – in higher education art and design has caused a research-based culture to manifest. In the past twenty years or so, those courses that were once overtly vocational and technique-led now have sharper emphases on contextual, critical and historical study. The integration of theory with practice has enabled many graduates to multitask, to be professionally independent and more intellectually ambitious.

Have a voice, express an opinion

The new visual polymath can be someone studying illustration, graphic design, fine art, animation or photographic media whose work is underpinned by an intellectual engagement with a subject. This could be in the sciences, culture and humanities, education and technology through research, collaboration, or other forms of knowledge acquisition – formal or informal.

The outputs for such practitioners may include books, academic papers and literature; magazines; newspapers; posters; online documents, blogs and postings; interactive media; moving imagery; exhibitions; lectures and conferences; broadcast; and performance. The impact and significance of such work will be judged through their creators’ success in discovering new forms of expression that will contribute to economic and cultural life via publishing, performance, museums, film and broadcast media.

The rationale for authorship and the polymath principle is ownership – having a voice, expressing an opinion. The idea that illustrators are evaluated and commissioned solely in their roles as art-directed image-makers needs to be reappraised. To embark upon a successful career in illustration and the graphic arts, practitioners will need to be educated, socially and culturally aware communicators, who make use of a wide range of intellectual and practical skills. They need to have ambition and the confidence that such things are possible.

Alan Male, Professor Emeritus of Falmouth University

First published in Eye no. 92 vol. 23, 2016

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. You can see what Eye 92 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.