Summer 2024

Archiving the archive

When the Type Archive left its London premises, its vast collection was disbanded and its working Monotype hot-metal plant moved to the National Collections Centre. Two long-serving volunteers talk to Eye about the challenges they faced and how the history of the Archive is now being preserved. Photographs by Philip Sayer [EXTRACT]

When the Type Archive in London was obliged to close, volunteers Sallie Morris and Richard Ardagh were on hand to ensure the institution’s legacy was preserved for posterity, through oral history, video, texts and an enormous catalogue of its unique artefacts, now in storage. The former circus elephant ‘hotel’ held a vast quantity of machines and materials that Type Archive founder Sue Shaw and fellow trustees saved after the hot-metal type division of the Monotype Corporation went into administration in 1992. Examples of each machine in the Monotype production line were transported from the village of Salfords in Surrey to Stockwell in October 1995 in what was known as ‘Operation Hannibal’. The equipment, a full industrial process that included casters, keyboards, irreplaceable letter patterns and unique matrix-making machinery, in total weighed as much as 139 elephants. Punches, matrices, charts and records were also preserved. The operation required two ten-ton lorries a day for seven weeks. The Salfords site, once the workplace of thousands, was later bulldozed.

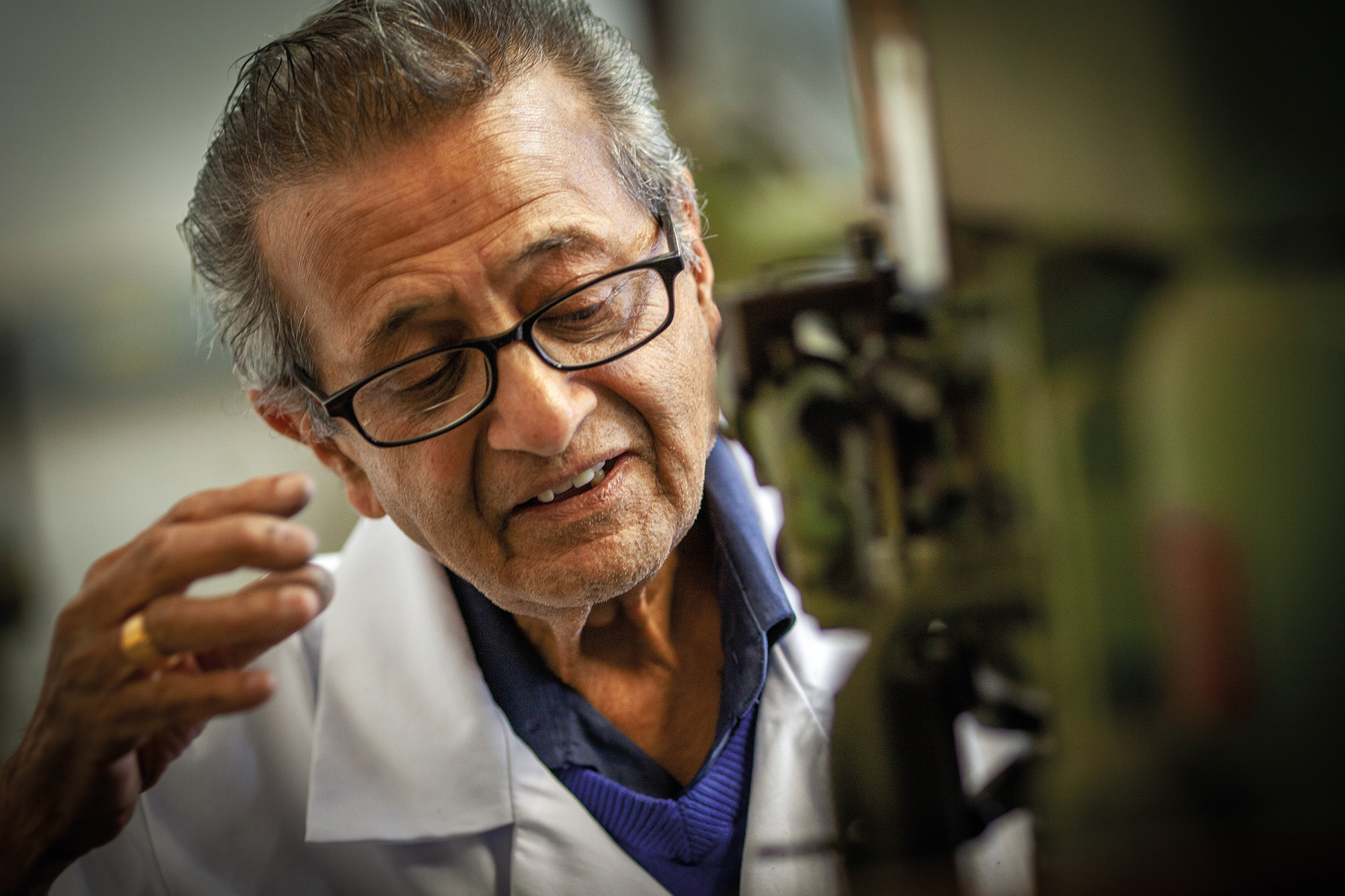

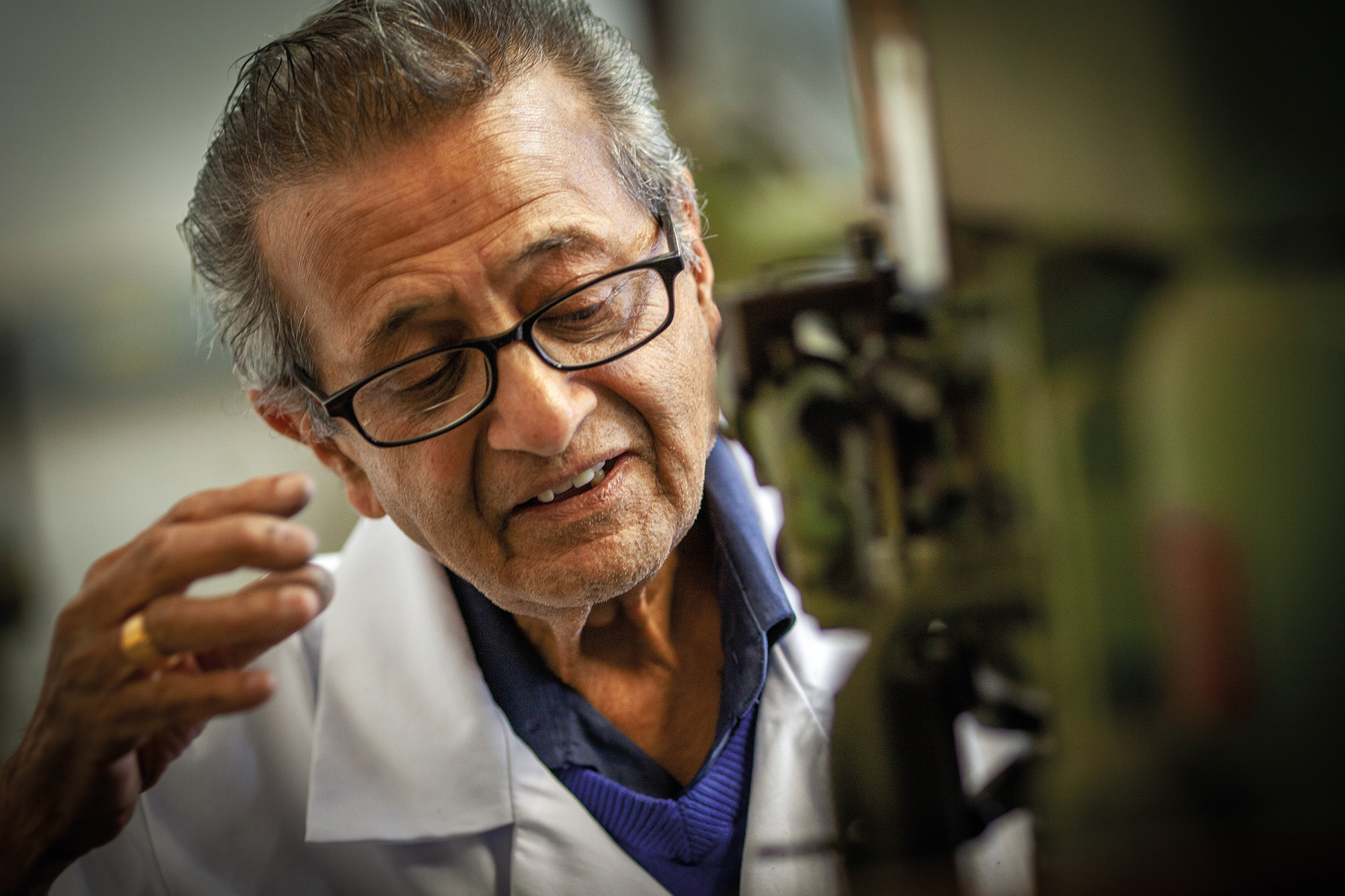

A small group of skilled ex-Monotype staff, including punchcutter Parminder Kumar Rajput, precision tool-maker Doug Ellis and manager Duncan Avery started a new company on the Type Archive premises: Monotype Hot Metal Ltd. From 1996 until 2023 the team continued to service orders from customers – many in Africa and on the Indian subcontinent – who relied upon Monotype equipment, spares, matrices and type to typeset for letterpress printing.

In 1996 the Archive rescued materials from Sheffield foundry Stephenson Blake, which included artefacts dating back to the sixteenth century, and the Robert DeLittle woodletter collection from York, plus private donations, such as the Desmond Jeffery collection (see Eye 90). This invaluable research resource became the National Typefounding Collection, comprising eight million artefacts.

For many years, thanks to the energy of Shaw, a small team of ex-Monotype employees and countless volunteers, the Type Archive continued as a charitable trust with a government grant from the DCMS. Though Shaw was able to welcome visitors from around the world by appointment, she never achieved her dream of converting the Stockwell buildings into a living, ‘working educational museum’, open to all. Shaw died in 2020, and in 2023 the Type Archive relinquished its premises in Stockwell and the Monotype Collection was returned to the Science Museum Group to be housed in its National Collections Centre in Wiltshire.

A series of short films commissioned by the Science Museum tell the story of the Type Archive’s Monotype collection and its significance for mass communication and culture, including archive footage of Shaw.

Eye talked to Sallie Morris and Richard Ardagh about the Type Archive.

When did you first meet Sue Shaw and become involved in the Type Archive?

Sallie Morris: I met her in 2012 at an Edward Johnston seminar. I was studying the design and manufacture of Monotype typefaces in the hot-metal era at the University of Reading and I said, ‘I’d like to come to the Type Archive.’ She replied, ‘I bet you would … But we can’t have people coming who aren’t prepared to contribute something in return.’

…

Richard: I began assisting Parminder Kumar Rajput and eventually specialised in punchcutting as well as matrix- making because we had this Hungry Dutch project [completed in 2019]. It was the first new font for hot-metal casting in 40 years, a commission from Russell Maret, a US book artist. It was the first time that a digitally designed font had been translated into physical patterns, punches, matrices, type and it went through the Monotype process and was given a Monotype series number.

Did the Type Archive have to close?

Richard: A significant amount of time and effort was spent by a small but dedicated team to find a way for the Type Archive to continue, whether joining or collaborating with other institutions or finding alternative premises, none of which was successful. But it was certainly explored heavily. And then Covid-19 came, which was an additional challenge.

And you ran out of options and of time?

Sallie: Yes, there was a lot of pressure …

…

Has your understanding of type changed from working so closely with the Type Archive collection?

Sallie: I have learnt so much from being part of a team where we have a shared passion for type design, typefounding and the Monotype hot-metal process in particular. Here you were able to see the machinery behind the matrix, the keyboard and the caster. You could see the matrices, the patterns and the punches … as well as the machines that make them.

Richard: Printing has existed for more than 500 years. For the majority of that time there is no documentation. You had to be shown, and learn these things physically, paying attention to the feel and sounds of materials and processes. So to feel part of that lineage only deepens my respect for the engineering minds who changed the world through these inventions.

Read the full article in Eye no. 106 vol. 27, 2024

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.