Autumn 1992

Comics for damned intellectuals

Art Spiegelman

Françoise Mouly

Joost Swarte

Gary Panter

Charles Burns

Javier Mariscal

Robert Crumb

Sue Coe

Jerry Moriarty

Mark Beyer

It is ten years since Françoise Mouly and Art Spiegelman impetuously founded Raw Books and Graphics. Since then, Raw, the couple’s alternative comic strip magazine, has provided an outlet for talented unknowns, given new significance to the term ‘graphic novel’, almost single-handedly reinvented one of America’s most popular indigenous artforms – all on a shoestring budget.

Françoise Mouly and Art Spiegelman were married in 1982. Within a few months they gave birth to a publishing business which they named Raw Books and Graphics. It was consigned to a corner of their industrial living loft in Manhattan’s SoHo district, where it quickly grew into a healthy concern. Mouly, a native of Paris, had been an architecture student at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts and worked as a colourist for Marvel Comics in New York; Spiegelman, a native New Yorker, was an underground comic strip editor and artist with a unique analytical approach to comic page construction. The comics brought them together; and because they agreed that viable outlets did not exist in America for the kind of experimental work that interested them, they decided to fill the void left by the demise of underground comix in the mid-1970s by starting a publishing venture that would somehow provide a forum for new and radical forms. This entrepreneurial commitment thrust them into the roles of publisher and editor, and more reluctantly into being the virtual foster parents to a group of artists whose unconventional styles and approaches were given little encouragement in mainstream publishing circles. Within a few years Raw magazine, the flagship of Raw Books and Graphics, had enlivened a moribund field.

The first issue of Raw (1980) ingeniously used a black and white drawing by Spiegelman, with a full-colour panel placed on the window.

Raw 7 (1985), with cover illustration by Art Spiegelman, of which the upper right-hand corner is torn off. A torn piece randomly selected from another cover is taped to the corner of page 1.

Reviving a dying form

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, underground “comix” were the spawning ground for the most outrageous and irreverent American comic strip artists since the 1950s, when Harvey Kurtzman’s satiric Mad comics revolutionised the form. Hundreds of counterculture “zines” were published across the country and sold in head shops and record stores. Yet by the mid-1970s, as interest in psychedelia and its trappings came to an end and crackdowns on obscenity and drugs closed the primary distribution outlets, the comix slumped into aesthetic and financial hard times. In 1974, Spiegelman tried to revive the dying form. As co-editor of Arcade, The Comix Revue, he opened a quarterly forum for the best underground comix artists to show their most recent work. But after a year and a half, and five difficult issues, he realised that editing was less satisfying than making his own comics. With Arcade’s demise, the underground was ostensibly dead, save for the occasional issues of the timewarped Zap and Gilbert Shelton’s The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers.

Spiegelman continued to make his own comics for a dwindling, albeit diehard, audience, but his work was evolving beyond the accepted conventions. His strips had always been more cerebral than the 1960s comics, with their sex, drug, and rock ‘n’ roll conventions, and he had never locked himself into one style or signature drawing approach. Spiegelman quoted liberally from art and comics history to communicate his decidedly complex stories and messages, seeking to co-mix (hence his use of the word “commix”) formal and conceptual aspects of comics design by looking inward at both the form and himself.

Portrait of the artist as a young man: a self-portrait of Art Spiegelman from the cover of his first monograph, Breakdowns (1977), the book that signalled a revolution in American comics.

Experiments with autobiography

Today critics see Spiegelman has a post-modernist, yet he was always concerned with the tectonics of the strip, from its basic design through to the printing processes, and a number of strips are deconstructions that explore the comic’s inner workings. He also experimented with autobiography, which was never as intensely explored as in his strip “Prisoner on the Hell Planet”, first published in 1972 in Short Order Comix (edited by Spiegelman and Bill Griffith). This was Spiegelman’s memoir about the tragic effects of his mother’s suicide, rendered in a stark, expressionistic scratchboard style, and his first overt attempt at self-analysis. This strip and a very early version of “Maus”, Spiegelman’s critically acclaimed two-part, book-length comic strip memoir about the relationship between him and his father (a concentration camp survivor), were published in 1978 in his anthology Breakdowns. Unbeknown to readers at the time, Breakdowns signalled the future course of American ‘avant-garde’ comics.

Spiegelman continued his experiments with form and content through the late 1970s: he had strips in Playboy and High Times, and did some editorial illustration, too – including the first two-part, wordless ‘strip’ for The New York Times op-ed page. But he was still seriously concerned with the degeneration of comics into a morass of superheroes and silly gags.

Mouly was likewise disturbed. She had been interested in comics in France, where the form is taken more seriously than in America. She even used comics to learn English, but found the sorry state of the art injurious to her language development. Having worked at Marvel, she was disgusted by the content of much of what was published and was frustrated that the only outlet for ‘alternative’ comics was Heavy Metal. Spiegelman and Mouly began to collect what they identified as avant-garde comic strips, if for no other reason than to prove that kindred spirits existed. Their discoveries pushed them into a vortex of European comics activity, and inspired them to import some of that energy to the United States.

The reasons for starting Raw Books and Graphics were compelling. As Spiegelman says about his own motives, ‘there was no place worth appearing in… there were magazines interested in me, but they wanted me to bend myself out of shape to do comics that would be fitting for them.’ Mouly had already single-handedly published The SoHo Map and Guide, an ambitious first project which sold advertising space to SoHo merchants. Now she wanted to learn printing, so they bought a used multilith press and rebuilt it in their loft.

Spiegelman and Mouly began by producing a series of ten Mailbooks printed on the multilith: eight-page, black and white, stapled booklets by vintage and contemporary artists (the first was a pick-up from turn-of-the-century cartoonist, Caran d’Ache). Other projects soon followed, such as the Zippyscope, a little box in which a ‘Zippy the Pinhead’ episode by Bill Griffith would roll past the viewer’s eyes. Each experiment increased Mouly’s familiarity with the press and when she reasoned she could handle a more complex project, the idea of starting their own magazine began to germinate.

Raw vol. 2 no.1 (1989), with cover illustration by Gary Panter. The first issue in a smaller, ‘more literary’, paperback form.

Catching the new wave

‘The real genesis of Raw,’ admits Spiegelman, ‘was Françoise’s goading it into existence, because it had a certain logic after she began getting involved in publishing. That meant setting up a makeshift distribution system so that things she printed could get around, which she did. And then her being ready to take on something more ambitious. For a while it seemed that might be books rather than the magazine, but the advantage after we did the first issue of Raw (which we swore we would never do again) was that we’d already set up something we could build on. A book is always another book, and requires a whole new constituency to be gathered each time. The magazine gave us a core of readers.’ The SoHo Map and Guide provided enough capital to publish a first issue, and the makeshift distribution Mouly had set up eventually paid them enough to keep going without further infusions of outside capital.

In a way, Raw evolved from Spiegelman’s anthology Breakdowns, at least in adapting the book’s expansive dimensions (11 x 14 inches), which enabled him to print his strips at almost their original size. There were other reasons for the new magazine’s format, too. ‘Raw started a time when there were a number of large-size cultural tabloids such as Wet, Fetish, Skyline, and Interview,’ recalls Spiegelman. ‘The only thing they had in common was the fact that they were ‘New Wave’, with a large size and a new sensibility. So whether it was fashion, architecture, art or politics, they sat next to each other on the newsstand. Whatever vestigial marketing sense I had said that if we did comics as a large-size thing, they could sit there next to the architecture magazines and nobody would offer the refrain of “where should the comic book go?” which we heard with Arcade.’

Abstract depressionism

From the outset, Spiegelman and Mouly wanted a three-letter title in the tradition of Mad. They went through many ideas before settling on Raw, which for them meant ‘having vital juices intact’ rather than untamed or aggressive. To this they added a new, enigmatic subtitle with each issue, among them, ‘The Graphix Magazine for Damned Intellectuals’, ‘The Graphix Magazine of Abstract Depressionism,’ ‘The Graphic Aspirin for War Fever,’ and ‘The Graphix Magazine that Overestimates the Taste of the American Public’. By comic book standards, Raw’s premiere issue was decidedly tame: every element was purposefully designed. But in the beginning, Raw’s design was a disquieting mix of what seemed like trendy New Wave detailing, and, by Modernist graphic design standars, a comic heavy-handedness. Every page had an obtrusive running head, an inelegant rule with a panel in which the artist’s name appeared, and a page number dropped out of a circle. Although this has become Raw’s signature design element, when it was first introduced it appeared a distracting conceit. Each contents page was an artwork in its own right, with overprints, drop-outs and other design details that echoed the Punk graphic aesthetic of the time.

Raw 1 was printed on heavy white paper and included a small comic book by Spiegelman called ‘Two Fisted Painters’ (one of his many strips devoted to exploring and satirising the comic form). The front cover had a colour panel pasted on it to give Spiegelman’s stark black and white illustration another dimension and to compensate for the lack of full-colour printing. ‘A lot of attention was paid to its object-ness,’ says Spiegelman, who was creative consultant for Topps Bubble Gum Company during that period, and has always harboured a fetish for novelty which he translated into the magazine. Though many of the strips were visually raw compared to those of slick mainstream comics, their surreal and heady unpredictability forced the reader to take notice. By Raw 5, which Spiegelman and Mouly agree was the most challenging issue, the various mixtures of typography, art and novelty were so well integrated that Raw’s style was decidedly its own. Raw had become a genre.

At the outset, Spiegelman and Mouly expected the first issue to be a one-shot, hence the first installment of ‘Maus’ didn’t appear until the second issue, and then only as a booklet insert because time was so precious that Spiegelman couldn’t work on something special for Raw and on ‘Maus’ at the same time. While Spiegelman was intensely involved with the hands-on editing of his contributors’ work – often as many as 20 pieces per issue – at the same time as working on various Raw One-Shot books and trying to complete chapters of Maus: A Survivor’s Tale (published by Pantheon Books in 1986), Mouly, as publisher and co-editor, devoted most of her energies to the intricacies of production, including design, print and binding, not to mention advertising, sales and the fulfilment of orders. She also supervised the volunteers who busily inserted bubblegum cards, records and stickers, and physically tore the covers of Raw 7, which had a missing piece in the right-hand corner. After Raw 7, the office moved downstairs, and a young cartoonist, Bob Sikoryak, was hired as associate editor, the only full / part-time employee, and a long-term backbone of the operation.

‘It was never meant to be a long-lived project,’ sighs Spiegelman, revealing his characteristic angst. ‘It was meant to be a demonstration of how something could be in a better world, and ended up having its own logic and momentum; it began, more or less, steering us rather than us steering it. And I think that’s still true.’ That momentum was generated in part by the Raw artists, who were being given a venue in which to grow and were not eager to give it up. ‘Once everything was set up,’ continues Spiegelman, ‘it was just as easy to feed it as to kill it.’

Mecca for visionaries

Raw certainly did fulfil a need, and became a veritable mecca for quirky and visionary artists and storytellers from all over the world. From the initial 5000 print run, subsequent runs increased incrementally to almost 20,000 by Raw 8, the last of the large-format issues. Among the relative newcomers were Gary Panter, who already had a cult following for his ‘Jimbo’ strip, which appeared in a West Coast Punk magazine called Slash; Charles Burns, who had only ever published spot illustrations before sending his meticulously drawn translations of 1950s horror and love clichés to Raw for consideration; Jerry Moriarty, who was teaching at the School of Visual Arts in New York and barely getting published before Raw picked up his ‘Jack Survives’, a surrealistic view of the banal; and Mark Beyer, with his art brut tales about depression and death. Other homegrown discoveries included Drew Friedman, Ben Katchor and Mark Newgarden.

Spiegelman and Mouly also published the cream of the European comic strip artists, including the brilliantly designed strips of Joost Swarte from Holland and Ever Meulen from Belgium; the explosive graphic fantasies of Pascal Doury and the noir storytelling of Jacques Tardi, both from France; and the seductive comicalities of the Spaniard Javier Mariscal. In his effort to separate Raw from underground comix, Spiegelman did not ignore the masters of the genre, and published new stories by Robert Crumb, Kim Deitch, Justin Green and Bill Griffith. He wanted to provide a forum for illustrators, too, but most of those he invited failed to produce. The most notable exception was Sue Coe, who provided some of the most strident polemical visual commentary in Raw, as well as two Raw One-Shot books, How to Commit Suicide in South Africa, a visual indictment of the effects of apartheid, and X, a paean to Malcolm X.

How to Commit Suicide in South Africa (1983) by Sue Coe and Holly Metz.

Conceptual detail

Raw One-Shots developed as the vehicle to showcase a body of work or to tell stories longer than could be handled in the magazine. The first was a collection of Gary Panter’s ‘Jimbo’ strips, which with their pan-cultural, post-nuclear, Nippomerican anti-hero have become a classic of abstract storytelling. Printed on newsprint bound between cardboard covers with gaffer tape, Jimbo was both an artist’s book and a comic book. ‘We wanted to make a book that’s a bubbling stew of acids that’s going to self-destruct,” Spiegelman notes. It also showed the attention to conceptual detail – even given financial concessions – that typified the Raw One-Shot. As difficult as they were to produce, and with the brunt of the labour falling on Mouly’s shoulders, Spiegelman pursued the look and feel of Raw One-Shots as an extension of his work at Topps Bubble Gum Company (where he devised Wacky Packs, Garbage Pail Candy, Garbage Pail Kids and Toothpaste Candy, among other novelties). ‘They’re part of the form following function idea, and were not grafted on arbitrarily,’ he insists. ‘It’s not as though Gary Panter’s work would have been well served by having an acetate cover in which the colour slid out – like we did with Moriarty’s Jack Survives – or that Moriarty would have been well served by the cardboard cover.’ Likewise, although Mouly would have preferred better production values for Sue Coe’s South Africa book, the newsprint does evoke the sense of emergency the subject demands. The formats of subsequent Raw One-Shots by Panter (Invasion of the Elvis Zombies), Coe (X) and Burns (Big Baby) were more or less dictated by economics, but retained the paper over boar look that reminded Spiegelman nostalgically of the ‘Golden Books’ he enjoyed as a child.

Spiegelman and Mouly see the Raw One-Shots as collaborative efforts, yet Spiegelman’s role as their draconian editor sometimes provokes his artists’ anger. Jerry Moriarty, who credits Spiegelman with giving him the necessary encouragement to ply his art, says that with the Jack Survives One-Shot, the relationship got messy. ‘I thought the book was going to be an artist’s book,’ he explains, ‘but it became an editor’s book, just like what happens when you’re an illustrator.’ The problem occurred with the cover, an acetate sheet on which the black plate was printed. If the cover shifted or was removed, only the untrapped color would show. Spiegelman thought it would suggest the ephemeral nature of comics; Moriarty thought it was a gimmick. A similar clash of wills occurred with Gary Panter’s third book, when the Raw One-Shots were being packaged for Pantheon Books. At issue again was the cover design. ‘Art has strong packaging ideas that override what anyone else wants to do,’ complains Panter. ‘I like to collaborate, but usually with people where the first condition is that no one gives a shit, and then something can grow out of it, which takes time.’

Artist and editor

Spiegelman concedes that being both artist and editor has resulted in difficulties with some of the artists. But until the publication of Maus in 1986, he feels he was still seen as one of the guys, ‘a peer who was also the editor. But after Maus was received as something of a much higher profile, it put me in a position where I had even more power, and that made it more difficult for people to allow me to exercise any control over their work.’ However, despite the inevitable complaints and resentments, most of the artists praise his editorial skills. Spiegelman is convinced about the rightness of his vision, but he does not discourage his artists from their own beliefs.

The year 1986 marked a turning point for Raw Books and Graphics. Maus was published by Pantheon Books, which also contracted Raw One-Shots by Mark Beyer (Agony), Gary Panter (Jimbo) and Charles Burns (Hard-Boiled Defective Stories), and an anthology of the first three issues of Raw called Read Yourself Raw. Around the same time, Raw 8 was published: the most ambitious of all and the most exhausting. Mouly was pregnant with their first child, and simultaneously had come to the point where the learning curve that had pushed her forward was flattening out. Moreover, the impetus for Spiegelman to finish Maus II was great. Spiegelman was also afraid of becoming a business, and aggressively avoided having a regular publishing schedule whereby his artists would appear in every issue: ‘That would be too predictable to remain interesting,’ he says.

Maus and Maus II, published by Pantheon Books. Both covers designed by Art Spiegelman and Louise Fili.

Page from Maus, ‘Chapter 2: The Honymoon‘, in the more economical style Spiegelman used for the book-length version.

Pages of experience

So Raw was put on hold until, as Spiegelman describes it, ‘I got the bug up my ass that started it off again. At a certain moment, Maus’s high profile made me think that what could be interesting would be to have a magazine that was constructed around the format and sensibilities of a literary magazine rather than a graphic arts magazine. ’ Spiegelman wanted to push forward the idea that this work was to be read as well as looked at, which required more space for the stories to develop. The proverbial bug made Spiegelman act: he and Mouly began raiding their files for work that would adapt to a new, more literary paperback format, similar to the size of Maus. They created a dummy the thickness of a telephone directory, which Spiegelman continually altered to achieve the right mix. Then they looked for a commercial publisher, eventually going with Penguin Books, which is also publishing the most recent Raw One-Shots by Drew Friedman (Warts and All), Ben Katchor (Cheap Novelties) and Charles Burns (Skin Deep).

When the new Raw vol. 2 no. 1 (subtitled, ‘Open Wounds From the Cutting Edge of Commix’) was launched in 1989, it had a print run of over 30,000. Yet some critics were angry that the new scale appeared to be an expedient concession to marketing pressures, while others mourned the passing of the behemoth version that had given such breadth to the graphics. Spiegelman believes it is a trade-off, but the virtue of a smaller size is that ‘One can go through more pages of experience. I’ve found that once you’re able to refocus your eyes what was happening within the scale you were given, all of what’s there still operates – though unfortunately for some artists this is less true.’

Pushing the limits

Three issues of Raw have been published in the new format, and again Spiegelman has put the magazine on hold to ‘buy some time’, despite the fact that Maus II: And Here My Troubles Began has now been published. Mouly is working with Sue Coe on her next opus, Porkopolis (a years-in-the-making exposé of American meat slaughterhouses and their effects on workers), which probably will not be done as a Raw One-Shot. In fact, Mouly has relinquished most of the daily responsibilities for Raw Books and Graphics, short of doing the work that only she can do, and has started taking pre-med courses at Hunter College in New York. Together they will edit Raw and the Restless, an anthology of Raws 4 to 8, while Spiegelman has plans to co-edit a new, non-Raw series called Neon Lit: adaptions of noir novels in small trade paperback format illustrated by former Raw artists and others. As for a new Raw, Spiegelman explains he is ‘not ready to think about another Raw, nor am I ready to dismiss Raw and bury it. So this allows some Raw project that ought to happen the space to happen, and then see if there’s room to make other Raws, probably in a third format.’

In the decade since Raw Books and Graphics was conceived, more Raw-inspired magazines have been published, some by Raw artists looking for other venues, and others by those who weren’t up to Raw’s standards. Graphic novels, a term Spiegelman hates, have become a fully-fledged publishing genre: some good, others no more than superhero pap with a hardcover and perfect binding. The tremendous critical reception afforded Maus and Maus II has validated Spiegelman’s long-held assertion that there is no subject that cannot be handled by the comics medium. And Raw itself has been seriously analysed for pushing the limits of the form, and for reviving the nascent intelligence of the American comic strip (‘Krazy Kat’, ‘Little Nemo’, ‘The Kinderkids’). This cottage publishing entity that Spiegelman and Mouly invested their hearts and souls into has in ten years, arguably, done more to awaken Americans to the integrity of the comic strip than all the efforts of comics writers, artists and producers since comic strips began in the American newspapers almost one hundred years ago.

Steven Heller, design writer, senior art director for the New York Times 1974–2007

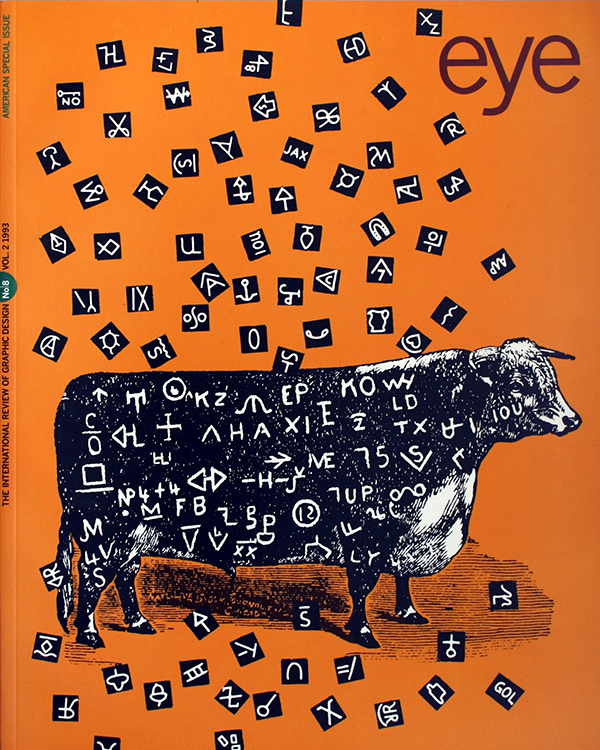

First published in Eye no. 8 vol.2 1993

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.