Summer 2009

Artwork and play

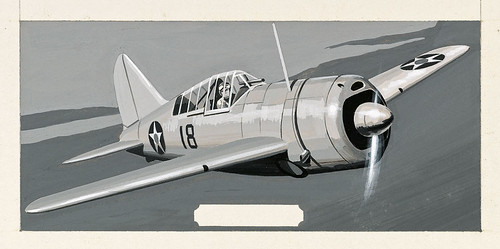

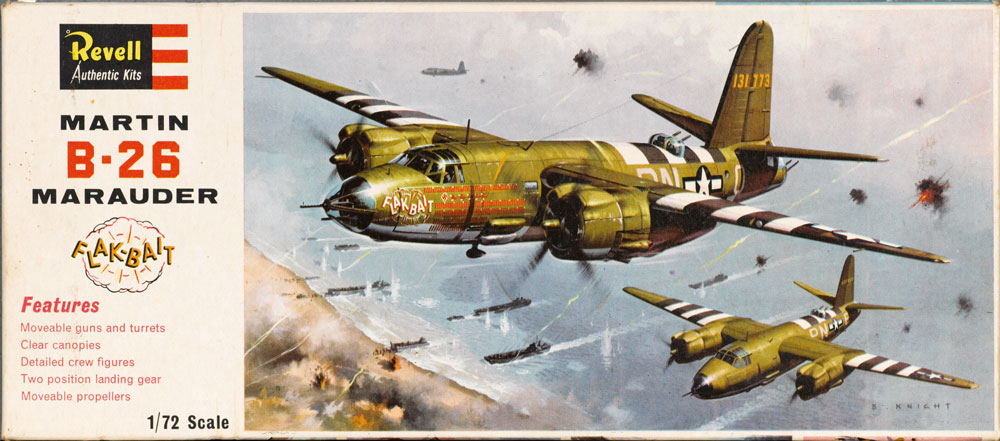

Brian Knight’s lovingly detailed paintings of ships, planes and cars trace an elegiac path for postwar industry

Brian Knight’s name is not widely known, but for many men who grew up in the 1960s and 70s his work will produce a start of nostalgia. Knight was one of the supreme artists of the Airfix box, painting hundreds of vivid, painstaking images of aircraft, battleships and fighting men. Memories of Airfix days are defined at least as much by Knight’s pictures, with their swooping perspectives and lush colour schemes, as by the drearier reality of grey plastic – streaked and blistered with unevenly applied poly cement. (And how far off those days seem, when Airfix glue was an accessory to innocent pleasure, not a pleasure in itself.)

The pictures on these pages are taken from an archive of Knight’s work unearthed by his step-grandson, graphic designer Matt Curtis. They evoke an era when making a living from such illustration required phenomenal manual skill and hard work. In interviews with specialist model-building and aviation magazines, Knight (who died in 2007) told stories of finishing work at ten in the evening to be woken at seven the next morning by an Airfix executive stopping by to see how hms Victory was coming along. Meanwhile, he was also drawing the instruction leaflets (see inside covers) and turning out box tops for Airfix’s rivals, the us-based Revell, which also made car kits, and the British FROG (‘Flies Right Off the Ground’, because it began with rubber-band-powered flying models).

In addition to his other skills, Knight had to be a good bluffer: when the opportunity to draw boxes for plastic soldiers arose, he fibbed that he knew how to draw figures and then had to labour to live up to the claim. Lacking experience, he would copy the faces of film stars: his boxes of HO-00 scale figures have Kirk Douglas staring incongruously out from behind a Soviet machine-gun in somewhere like Stalingrad, and Peter Lawford, Rat-Packer and Kennedy brother-in-law, in the uniform of a French infantryman of the First World War.

The illustrations in this vast archive show just how demanding a client Airfix could be. Knight’s initial painting of the German battleship Bismarck under attack by Fairey Swordfish biplanes, which he could reasonably have expected to elicit gasps of satisfaction, was met with a barrage of instructions about size and position of ship and planes, placing of the horizon, colour of sea and sky. No clicking and dragging: Knight had to draw a new set of ‘roughs’ (an inadequate word to apply to something so polished) and then paint the whole thing again from scratch.

The rates of pay were not impressive. A box of 1/32 scale soldiers, for example, a job that might take a fortnight, earned Knight £125 in the late 1960s. Each job and payment was entered in a neat ledger, which Matt Curtis also found among the artwork.

Knight began his career in 1940, aged fourteen, as an apprentice draughtsman at Miles Aircraft. Towards the end of the war he worked on the Miles M.52 experimental supersonic aircraft, but the project was abandoned by the government as too expensive. In the late 1940s he set up the technical illustration department at the Atomic Energy Research Establishment at Harwell, leaving after ten years because he could see no prospects for promotion. After a stint managing a commercial studio, he landed commissions with Revell, setting the course for the rest of his career. As well as kit boxes, he painted commemorative plates featuring First and Second World War aircraft.

So a set of skills learned working at the cutting edge of technology ended up in the service of play and nostalgia: it’s a dispiriting allegory of the fate of British industry in the second half of the twentieth century. Large-scale manufacturing has all but died; and so has Knight’s brand of illustration, all swept away by the digital tide.

The pictures in this Eye72 article are taken from an archive of Knight’s work unearthed by his step-grandson, graphic designer Matt Curtis. They evoke an era when making a living from such illustration required phenomenal manual skill and hard work …

First published in Eye no. 72 vol. 18.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue. You can also browse visual samples of recent issues at Eye before You Buy.