Autumn 2008

Awards madness

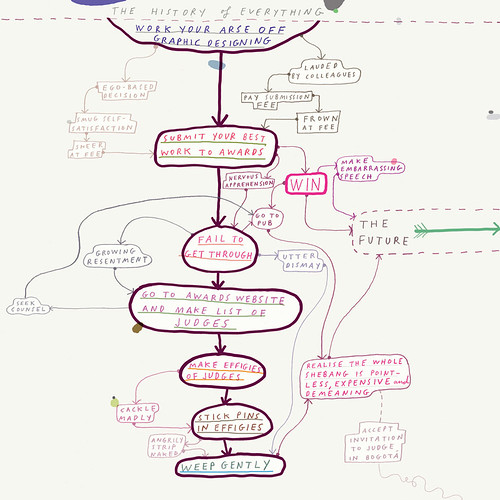

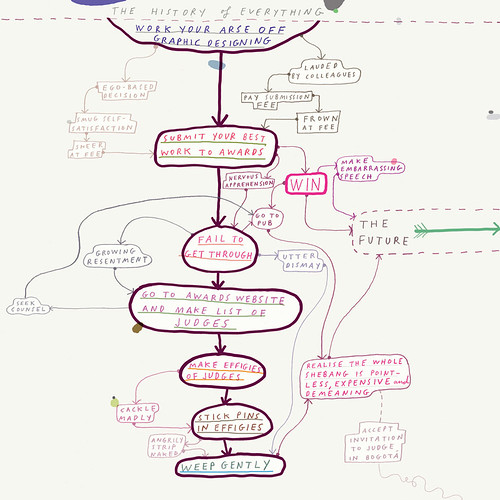

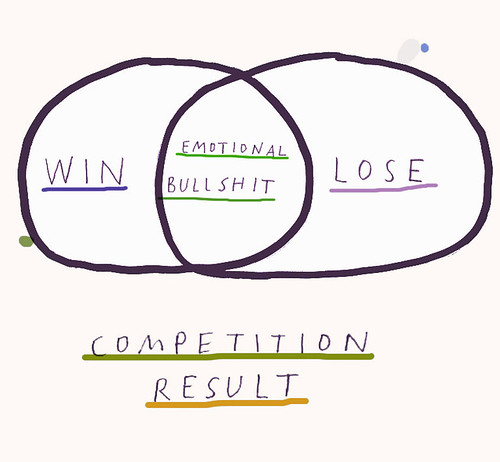

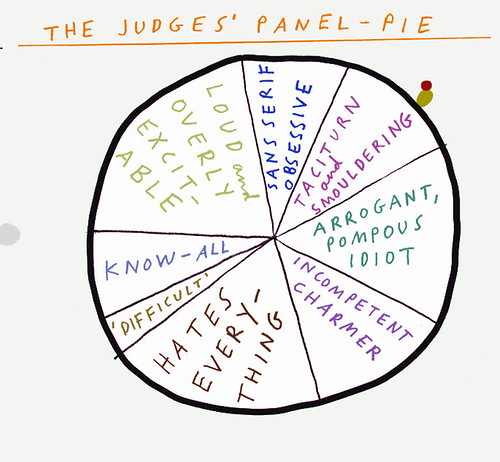

Everybody likes to win. But if design competitions destroy creativity and co-operation, what’s the point? By Jason Grant. Infographics by Paul Davis

To be Number One, the champion, the winner – it’s a natural human aspiration, an irresistible biological imperative that inevitably breeds competition. Consequently, awards are epidemic: even the competitions are competing. In the realm of graphic design, there are thousands of awards: D&AD, Webbys, the European Design Awards, Art Directors Club awards, Tokyo Type Directors Club awards, YoungGuns, Red Dot awards, Young Asian Designers, even a Seoul Design Olympiad.

There are competitions run by magazines, paper companies and software companies. There are international poster annuals, biennials and triennials. Competitions for the design of T-shirts, logos, stickers, banknotes, flags and stamps. Real-time gladiatorial contests such as Cut&Paste’s Digital Design Tournament and Layer Tennis. And when entering them leaves you designed out, you could write about it and enter the Winterhouse awards for design writing and criticism.

But is competition really unavoidable? Is it even desirable? Are awards really a useful way to ‘bring out our best’? Design awards usually have admirable goals. Part of D&AD’s mission is to ‘set creative standards, educate, inspire and promote good design and advertising’. The Art Directors Club ‘celebrates and inspires creative excellence’, ‘promoting the highest standards of excellence and integrity in visual communications’.

Even if we take a critical or cynical stance against awards, existing assumptions about the inevitability and value of competition, and the struggle to conquer each other generally, are rarely challenged.

Social psychology

However, research belies the assumption that competing leads to better work. Morton Deutsch’s social psychology experiments with university students found that awarding victorious competitors not only had no effect on how well they performed but in tasks that relied on working together produced significantly poorer results. In his book No Contest: The Case Against Competition, 1986 / 1992, Alfie Kohn surveys research from education, economy, sports, the arts and other fields and the evidence is counter-intuitive yet unequivocal: competition mostly results in poorer performance, reduced satisfaction and less creativity. Yet in the historical contest between co-operation and competition, competition whipped co-operation’s ass real good. It is the cornerstone of modern global economy and ideology. Competition is presented as an antidote to monopoly, mediocrity and even totalitarianism, though rarely as ingrained rivalry that manifests itself in war, poverty and environmental ruination. Could we imagine a cultural landscape without it? Wouldn’t all visual communication look predictable, disconnected and, well, like the content of a lot of design awards annuals?

Top and below: information design by Paul Davis.

The phenomenon of the cultural prize – the singling out of an artist, writer, architect, musician, actor or designer – dates back to at least the sixth century BC with the Greeks’ drama and arts competitions. It gathered momentum through the Classical, medieval and Renaissance periods, but the twentieth century saw the explosion of creative competitions – what author James F. English called The Economy of Prestige (in his Harvard University Press book of that name). English laments the conflation of sport and art, arguing that they are contradictory facets of life: ‘Cultural prizes represent an external imposition on the world of art rather than an expression of its own energies. The rise of prizes . . . especially their feverish proliferation in recent decades, is widely seen as one of the more glaring symptoms of a consumer society run rampant . . . Prizes . . . are not a celebration but a contamination of the most precious aspects of art.’

Good for business, good for egos

Designers enter awards for all kinds of reasons. We want our excellence rewarded. We want recognition personally, for our businesses, and also for our clients. After all, prizes are tangible when so much of what we achieve is slippery and unaccountable. ‘When I work I am often teetering between thinking that what I’m doing is really good or really awful,’ says Martin Venezky of Appetite Engineers. ‘So any form of external acceptance is very comforting.’ David Palmer from Love said (of winning at this year’s Design Week awards): ‘It’s great for our profile. But it’s also good to go back to our client and reward them for allowing us to do what we wanted with that job.’ Awards are perceived as a tool for attracting and flattering clients. Vince Frost, now of Frost Design in Sydney, began entering awards after observing in his last days at Pentagram that the company was built on the reputation of its partners. ‘Without a reputation people don’t know that you exist and therefore no work comes your way. I left to start my own company of one! And the realisation that design is a business hit me on the back of the head.’

We are fairly comfortable admitting to these mercantile manipulations, but less so to our own egocentric panderings. How often do you hear an acceptance speech that thanks everyone for making me feel like a big hero, for example? Awards can also be seen as a way to knock industry stasis. Jonathan Barnbrook says he wanted to prove that ‘actually a small design group could do much better work than the big design groups. Also, of course, I wanted a little bit of approval, but I am fine now thanks.’

Frost remembers winning his first award: ‘I was totally excited. Me sitting working in my spare bedroom in my boxer shorts won against the big boys.’

Expensive hobby

A common reason given for not entering awards, and for the lionisation of a certain kind of work, is the expense involved. Competitions are often played as a gamble and therefore the more times a studio can afford to enter, the more often it is likely to win. ‘We entered awards very regularly until eight years ago,’ says Erik Kessels from KesselsKramer. ‘Then we stopped, because entering them cost us a fortune – we were spending up to 80,000 Euros a year on fees.’

‘It used to be that winning these competitions was the only way to make a name for yourself,’ claims Michael Bierut of Pentagram and Design Observer. ‘Now, in the age of blogs, etc., all bets are off.’ But before awards were so prolific, didn’t designers mostly make a name for themselves with work that fulfilled or even transcended social and cultural need? Is this a redundant aspiration? Bierut believes that online exposure is diluting the lure of awards. How then to explain their ever-increasing abundance?

Non-Format’s Jon Forss comes clean: ‘Awards are basically a drug: the first hit is amazing, which fuels a desire for more, but it all depends on the standard of the competition itself. The more prestigious the awards, the bigger the buzz. There are a great many award schemes out there but we limit ourselves to only a select few. You could say we’re on to the hard stuff now.’

As the competitor’s status is boosted by winning an award, the competition’s prestige is enhanced, too, by its consecration of already culturally revered figures. Most major competitions in the broader cultural sphere – the Nobel, the Pulitzer, the Pritzker or the Grammys – are safely ‘recognising’ already oft-awarded individuals. It is only a matter of time before graphic design has its equivalent. The game is a climb up the hierarchy of prizes. Similarly, no creative competition can achieve much symbolic cultural value if the jurors are not at least near the top of their fields. And it is increasingly difficult, in turn, to imagine these figures achieving such esteem without the momentum of awards.

Judges and juries

Designers judge awards for many of the same reasons they enter them. It is rarely for direct financial benefit; if payment is offered it is generally a token compared with the juror’s usual income. So it is the cultural capital that is most valuable – a status that cannot be bought. Jurors’ aims are also often ethical and philanthropic. They champion the various stated aims of the competition: to reward excellence; publicise worthy projects and organisations; assist marginal designers; celebrate a creative community; or honour the memory of the deceased.

For some, the jury process is a disillusioning revelation of corruption and incompetence – Stephen Banham from Letterbox in Melbourne defines an awards enthusiast as ‘somebody who hasn’t been on a jury yet’. He remembers one occasion when ‘we had a juror vigorously lobbying for his own work to get an award’.

However, most design judges say that the first-hand exposure to a diversity of work, and the interactions with other jurors often justify the whole event. Barnbrook occasionally judges awards and finds some very enjoyable, ‘but usually it’s because of the other jury members’. Ralph Schraivogel says: ‘It is interesting to see design with the eyes of others.’ Nick Bell says: ‘No matter what you think of graphic design awards, they tell us one thing for sure: that none of us agrees.’ Amy Franceschini from Futurefarmers says: ‘The most exciting part is the conversation and debate among jurors. Just think what we could learn from this closed-door process if it were made more transparent.’ She adds that there could be merit in entrants choosing the jury: ‘Who would you want to judge your work?’

The 100 Show, one of the most interesting competitions, had a relatively ambitious curatorial agenda. Instead of attempting consensus, the jurors independently selected work from the submissions and then not only commented on their selections but also wrote about the experience in the American Center for Design’s annual book of the awards. The jurors consistently protested that there was not enough time for thoroughness. That better work existed to their knowledge and wasn’t entered. They wondered how, removed from its context and severed from its audience, work could be judged effectively. What emerged over the years was a recurring list of complaints and concerns about the legitimacy and value of awards – though never about the idea of competition itself.

Jurors tell the same stories today. ‘By and large, they are judged to the best of the judges’ ability,’ says Stefan Sagmeister. ‘Where judges have to go through vast amounts of entries, like at the New York Art Directors Club or Communication Arts, subtle work is at a severe disadvantage. Only the bold and big really gets noticed.’

Anja Lutz from Shift judged the ADC awards last year: ‘We were judging eight hours straight for three days in a row. I doubt that after the first hour any of us were seriously able to judge any work beyond the initial visual impact and surprise factor. But we had a good time.’

According to Forss, who sat on the 2007 D&AD jury, there is ‘an enormous amount of luck’ involved in getting a piece of work through to the final rounds of the judging process ‘The really unlucky people have their work judged first, when the utopian ideals of the judges have yet to be beaten down by the rigours of the day. One of the major quandaries is whether to judge a piece of work on show by one’s own standards of good or bad, or by the standard of the rest of the work on show. At the beginning it’s easy to set a high standard by which to measure the work, but by the end of the process one tends to be more and more lenient, compassionate and merciful.’

Beyond the beautiful cow

The refusal of the jury at this year’s D&AD Awards to give any prizes in the graphic design and book design categories caused outrage and debate (see Nick Bell’s ‘Confessions of an awards juror’ on blog.eyemagazine.com). However, such gripes have always been as much a part of awards events as backslapping, drinks parties and phallic trophies. Meanwhile, competition is so deeply ingrained in every aspect of our lives – indeed as a lens through which we filter our lives – it escapes scrutiny. We just assume it is a natural rather than cultural condition. But in fact we’re taught to compete as soon as we’re taught anything.

Sir Walter Scott, in an 1821 argument against literary awards, declared that with jurors ‘differing so widely in politics, in taste, in temper and in manners, having no earthly thing in common except their general irritability of temper and a black speck on their middle finger, what can be expected but all sorts of quarrels, fracasseries, lampoons, libels and duels?’ But although the diversity of a jury is now seen as an important requirement for achieving representative results, it is difficult to imagine much brave and impassioned polarisation among contemporary awards jurors. The consecration of prizewinners generally works to legitimise and indoctrinate dominant values. Awards are persuasive instruments of control. To enter a competition is to submit to authority, to concede bureaucratic command over a feral cultural terrain. For Barnbrook there is something ‘very conformist about winning an award’. Entering an award is to conform to an edifying hierarchy and to queue for a place in its history. Bell believes they can lead to an ‘over-emphasis on the aesthetics of craft. The kind of debates that take place on D&AD juries would back that thesis – great ideas being passed over because “I didn’t rate the type”.’

Slovenian design theorist Oliver Vodeb agrees: ‘Many designers are experts in decoding what kind of work will have a chance of winning which award. The competitive context not only shapes the nature and quality of the outcome but affects the whole philosophy of design. It creates a mindset of decontextualised design thinking and practice. It reduces design, design thinking and practising to a self-referential commodity.’

Rudy VanderLans, in his 1996 essay for the 100 Show’s The Seventeenth Annual noted: ‘This show was marked by two things: the near total absence of magazine and music packaging, two areas where American graphic design pushes boundaries rigorously, and the staggering number of paper promotions and annual reports, two areas where American graphic design splurges. If it wasn’t for corporate annual reports and paper company promotions, I wonder if design competitions like this could even exist.’

The organisations that run awards can lack this sense of perspective, overstating and confusing their role. The website of the Australian Graphic Design Association (www.agda.com.au) starts with a claim of reasonable ambition: ‘The most important reason for the AGDA awards is to document and celebrate Australian graphic design every two years. It is a pertinent snapshot of where our industry has been and where it is headed.’ However, it ends with: ‘Without it there would be no dialogue, no history, no continuity, no critical analysis, no passing on of knowledge and no exchange of ideas.’

So our whole history and critical capacity depends on designers vying for superiority and compliments? Maybe we should listen more closely to designers who just don’t see the point: ‘For us it is interesting to see how our projects work in life,’ says Marco Fiedler from Vier5, ‘not what a jury thinks. An award is something like winning a prize for the most beautiful cow.’

Can we find new, more constructive ways to encourage and recognise great work? In spite of our misgivings about competitions, my studio, Inkahoots, sits on the jury of Memefest, the Slovenia-based ‘international festival of radical communication’ (www.memefest.org).

The aforementioned Oliver Vodeb established Memefest to nurture and reward innovative and socially responsible approaches to communication. While acknowledging that ‘competition, and dividing winners from losers, is a fundamental part of the ideology of neoliberal capitalism and is also a result of market driven communication such as advertising’, he doesn’t agree that there’s a contradiction between the festival’s goals and its competitive context.

‘To say that the competition itself produces only winners and losers is an exaggeration that dismisses the complexity of the process. There are no stars at Memefest and the whole process is open to critique and is inclusive instead of exclusive. This educational dimension is fundamental to our philosophy. The whole process is much more formative than selective.’

An alluring fantasy

As philosopher John McMurtry said, ‘Presuming that the contest-for-prize framework and excellence of performance are somehow related as a unique cause and effect may be the deepest-lying prejudice of civilised thought.’

How, then, do we achieve excellence? Well, when we focus on mastery rather than victory. When we are enthused and challenged and connected socially. Designers are increasingly realising the rewards and necessity of collaboration. We succeed more often when our motivation is intrinsic not extrinsic. And when we focus on what is really at stake.

We probably won’t agree on what exactly this is, but we can stop denying that there is a compelling consensus that demands urgent change. Pretending is a creative prerogative, and awards are an alluring fantasy. But imagining a better future is a greater creative privilege. This is a future of commonality and co-operation, not of distraction, division and competition.

First published in Eye no. 68 vol. 18 2008

Information design by Paul Davis.

First published in Eye no. 69 vol. 18 2008

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.