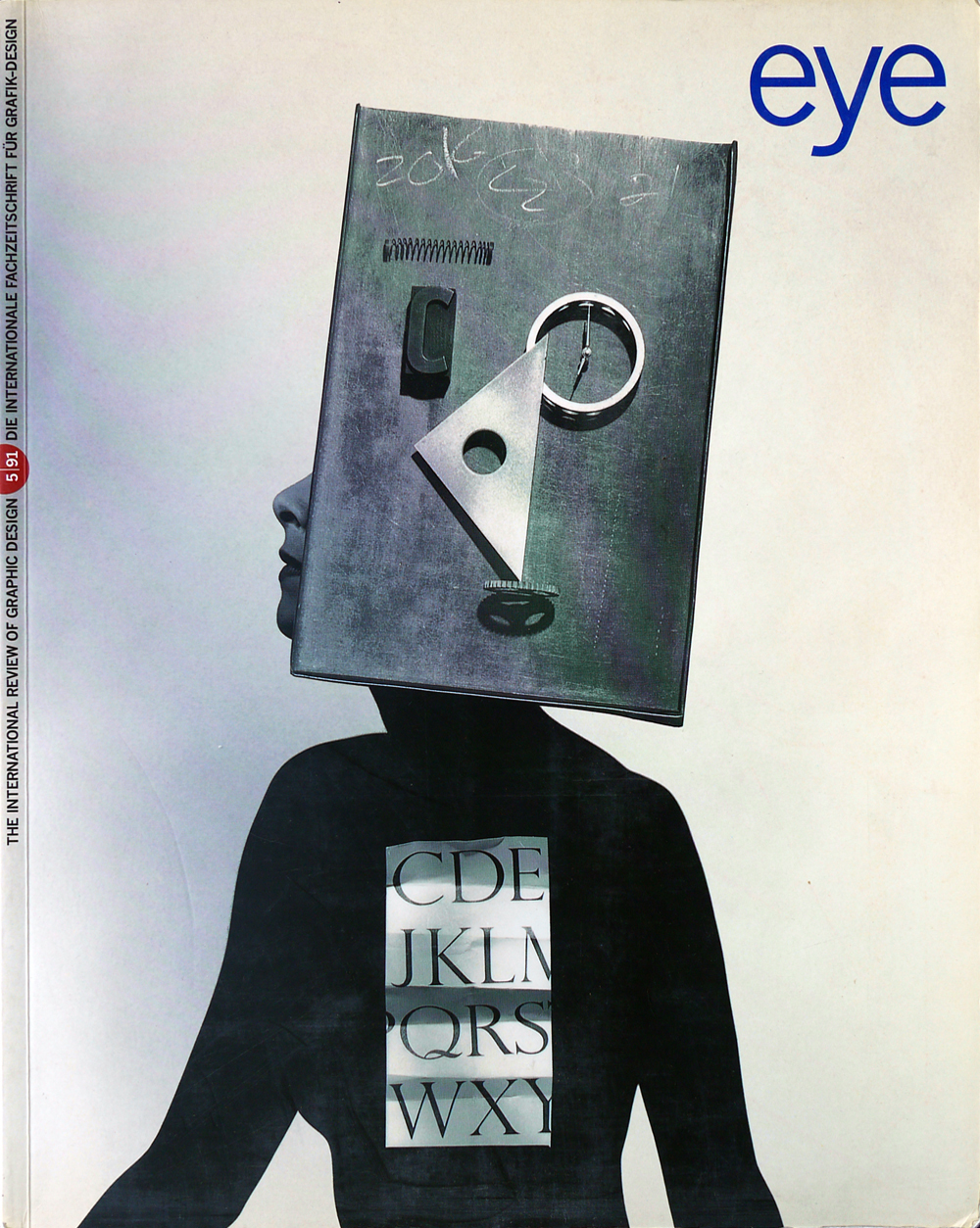

Winter 1991

Reputations: Barbara Kruger

‘I’m someone who works with pictures and words, and people can take that to mean anything they like.’

Eye talks to the American magazine designer turned media artist who uses the tools of advertising and graphic design to confront and question her audience

Barbara Kruger was born in Newark, New Jersey, in 1945. She attended Syracuse University before, in 1965, beginning classes in fine arts at Parsons School of Design. Abandoning her studies, Kruger took a job designing small ads at Condé Nast. Promotion came rapidly; so did disillusion and, in 1969, Kruger turned to the world of art. Her first pieces were large woven hangings. She began to publish poetry, supporting herself as a freelance picture editor. By the end of the 1970s, Kruger was an established figure among the New York artists concerned with media presentation. The ‘demystifications’ of popular visual language created since the early 1980s are remarkable for their graphic economy.

Karrie Jacobs: Your work could be seen as a reaction to the way that fashion magazines look – the way the words on the cover don’t quite mean anything or relate to the image.

Barbara Kruger: That’s a good observation. On a formal visual level, I’d say that about 85 percent of my work as an artist has been informed by my job as a graphic designer. People who don’t understand or don’t know about the history of graphic design - if they’re mainly art historians - might just look at my work and say “Constructivism”or “John Heartfield”. As someone who only went to art school for a year and a half, I didn’t know who Heartfield was until I curated a show at the Kitchen, new York, in 1980 and someone asked me why there was no Heartfield in it. Critics always focus on the fine art/Constructivism end of my work, rather than thinking that this was somebody who had a job, who had a training in cropping photographs and who pasted words over them. And those words, when you were in a layout department, didn’t say anything they just said, “A, B, C, D, E, F, G”. My job afterwards as an artist, in many ways, was to make that sort of device meaningful.

Barbara Kruger, Untitled (Help!), 1992.

Top. Opening spread from ‘Barbara Kruger: Reputations’, Eye no.5, 1991.

KJ: Often, even when the dummy type is gone and the real type is there, the words still don’t say anything.

BK: My work tries to be substitutional, to somehow inject meaning where the message had previously been: “Buy this sweater, it’ll change your life.”

KJ: You worked with Marvin Israel, who art directed Harper’s Bazaar after Brodovitch, and Diane Arbus when you were in school. Did they influence your view of the world, or your use of visual material?

BK: I was at Parsons School of Design for about nine months, and at a very impressionable period. I was about eighteen or nineteen. Diane was interesting. In some ways I didn’t relate to her at all, but she was the first female role model I had ever encountered who didn’t wash the kitchen and bathroom floor seven times a day. She was trying to define herself through work outside of that domestic activity. This was in 1965. Marvin Israel was really important because he was the first person that ever made me feel special. You felt that you could, oh, just put together a portfolio and go around. At nineteen I left school and put together a portfolio. I have no academic degrees at all - I just went.

KJ: Was your portfolio painting or drawing?

BK: No. I did a portfolio of book covers – books I hadn’t read yet. I was also very influenced by the English magazine, Nova. So I did a few mock editorial pages, and I also had my fashion illustration, which I had been into in high school. I was also hired as a telephone operator secretary at an advertising agency, and then I went to Condé Nast. It was my first design job, although I had done freelance illustration for Seventeen. I did socks and jewellery and stuff like that.

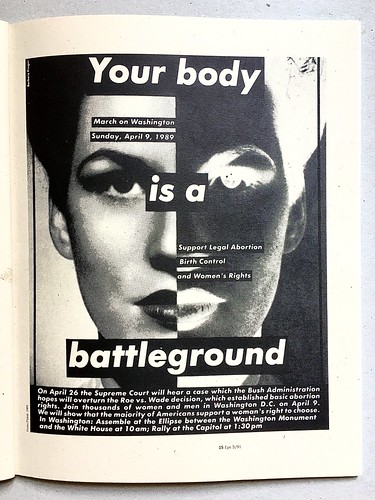

Spread from ‘Barbara Kruger: Reputations’, Eye no.5, 1991, featuring Kruger’s Our Leader, 1987; Untitled (Endangered Species), 1987; and Untitled (Your body is a battleground), 1989.

KJ: What was your work like there?

BK: I started at Mademoiselle when Roger Schoening was the art director. There were only two people. There was the head designer, the person who did the back of the magazine, a paste-up person and the secretary. In any event, the woman who was the head designer had been doing the bulk of the book. About six months later she left and I found myself – at this young age – doing the magazine. I only worked full time at Condé Nast for about four years, after which I continued working there as a freelance. I started doing a lot of book covers for people like Harper & Row and Schocken, designed an issue of Aperture, worked at Condé Nast as a freelance picture editor, then left Mademoiselle and started at House and Garden. That was all right until Alexander Liberman started looking in. Then we had to do twelve layouts for each spread. We couldn’t paste anything down; we had to fold it. Everything was provisional, so that he could walk in like the Prince of Wales and see 12,000 layouts with very slight increments of difference – like this much. I just couldn’t abide that abuse of power! It was just like a ritual.

I desperately needed the money and I decided that working as a picture editor was a way to avoid that. I could be in a darkroom, go through all these slides with a projector, then take all the two-and-a-quarters and the slides that I had picked and spend the whole day peering through a loupe at the pictures, until cropping, cutting and pasting became second nature. I could just look at something and see what I could use.

KJ: Find the picture in the picture?

BK: Sure. It’s something that you just know when you work at something as a job. Sooner or later, you know; that’s what happens. One of my greatest frustrations has been having to deal with an art subculture that has no understanding of what I’ve just said to you.

Spread from ‘Barbara Kruger: Reputations’, Eye no.5, 1991, featuring Kruger’s Untitled (When I hear the word culture I take out my checkbook), 1999; Untitled (We don’t need another hero), 1987; Untitled (Business as usual), 1987; and Untitled (I shop therefore I am), 1983.

KJ: Because ordinary things don’t inform the art world?

BK: Exactly. But it’s also not being able to hear difference. Like if I say to someone: ‘Yes, I respect what you’re saying, but my experience has been different.’ Don’t get me wrong! The art world has been incredibly receptive to my work. It’s the historical interpretation of who I am that misses the mark.

KJ: So in some way do you still feel as if you’re doing design or advertising?

BK: I don’t use those words. I always say that I’m someone who works with pictures and words, and people can take that to mean anything they like. People often use words like “appropriation” or “media art”, whatever that is. For me, they’ve used the word “advertising”. But I’ve never worked in advertising – except as a telephone operator. I’ve always worked in editorial design. People don’t even make the distinction; they don’t appreciate what page design is and the seriality that goes with it, and how that informed my work.

KJ: It seems you chose a way of using type that gives your work a certain consistency. Was this a conscious decision or something that just happened?

BK: I like it. Years ago I thought I wanted to make a movie, but I’m a failure as a masochist. Do you know what it’s like trying to get a film distributed, let alone made in this country? If I made a movie, it would not be black and white with words on it. There are a million ways of trying to be effective.

KJ: Why do you always use Futura?

BK: I’ve done pieces that don’t have Futura. Actually, when I need type that has to be set very tightly I always use Helvetica Extra Bold caps because it sets tighter than Futura. It cuts through the grease. That’s why I like it. I don’t like to talk about my influences, but certainly they include 30 years of New York tabloid newspapers, plus the films of Sam Fuller, that black and white stuff.

KJ: How do you reach people politically? How do you become effective?

BK: It happens in a lot of ways. People often say to me: “Well, you’re interested in mass communications, you’re interested in the media – do you want to do television?”I have no delusions about that. I know the people that I can reach and I feel that if I did TV, I wouldn’t want my work in some art show ghetto. I’d want to write a sitcom. I think we work for change in areas that we feel most fluent in. For instance, if you teach, you can make changes in an incredibly powerful arena. Or you can work in a subculture like the art world. People say: “Oh, everybody knows that it’s preaching to the converted.” Oh, yeah? Do you think that there’s no abuse of power in the relationships between people who go into galleries? Do you think that there isn’t racism in these people and in their relationships? Well, I think it’s ridiculous to cede any arena. It’s so shocking to me that either I, or Cindy Sherman, or Jenny Holzer will do shows, and the people who write about it will say, ‘Who is this white, male figure that these women think is such a problem?’

KJ: Is there a way to respond through art or graphics that will make a difference?

BK: Of course! When I first found out two years ago that there was going to be a march to Washington [in defence of women’s reproductive rights], I called the National Organization of Women. I said: “Can I volunteer my services?” They never called me back. Then I called the National Abortion Rights Action League. They were nicer, a little hipper, but forget it! They just said: “Well, we have someone that we use pro bono.” Finally, I got frustrated and did it myself. I went out with my students at the Whitney and we were out until 5 o’clock in the morning for about a week, putting up the ‘Your Body is a Battleground’ posters.

Then, about 8 months later, this PR firm that deals with the art world went to NARAL and said: “We can raise money for you.” This was before art world collapsed and auctions were still making some money. I did another “Your Body is a Battleground” poster for them. The PR firm brought NARAL my image, and the people at NARAL said: “It’s too strong. We don’t want to use it.” It was a picture of a woman’s face. So I said: “Could you please tell them that the Right is using pictures of fetuses? What is so strong about a picture of a woman’s face?” Finally, they got through to Kate Michaelman [the president of NARAL] and she said “It’s wonderful. Let’s do it.” But I found all this really shocking. What are they thinking?

Spread from ‘Barbara Kruger: Reputations’, Eye no.5, 1991, featuring Kruger’s You are not yourself (1984); Untitled (I am your reservoir of poses), 1982; Untitled (Buy me I’ll change your life), 1984; and Untitled, 1990.

KJ: Do you ever consider designing posters for political candidates?

BK: What candidate would I want to do a poster for? That’s the horrible thing. A bunch of failed hacks? Who? That’s the problem. You see, to me, politics is everywhere. I would rather do it around an issue, because the [1992 presidential] campaign is not going to be about personalities.

KJ: What do you think when your own work is appropriated?

BK: I think it’s fine! The only thing that irritates me is when it’s not good. I don’t call myself an appropriation artist, but a few dumb critics have. Wouldn’t it be ironic if an appropriation artist complained she was being ripped off? Basically, I don’t mind at all.

KJ: What are you appropriating?

BK: Photographs, images. I have no proprietary relationship to those images at all. But what really gets me is that there are some people getting mileage out of bad versions of Jenny Holzer and me. I don’t mind it in the proprietary sense, but it just doesn’t work; it’s not doing it in the right way. So it becomes either poetic, or it doesn’t have a heart. I have a commitment – physically, as a woman – just as Gran Fury, as gays, have a commitment in the AIDS epidemic. But a lot of people appropriate this approach, without committing themselves to it.

KJ: What inspires you when you are doing a piece?

BK: I’m not inspired. I can’t use that word.

KJ: Well, what motivates a poster? Is it a phrase in your head, or an image you see?

BK: It’s both – it’s almost simultaneous. At the moment, I’m doing billboards in Japan, in Berlin and in Warsaw, where a young woman approached me who’s a curator at a contemporary art space in a castle. I thought that I would do something on the roof and on the stairs leading up to it. Then I called her last week and she said that something fabulous had happened. Since we spoke six weeks ago there have been hundreds of billboards constructed all over the city.

Barbara Kruger, Untitled (Your body is a battleground), 1989.

KJ: They never had billboards before and now they have them?

BK: Yes. Had you been to East Berlin before the wall came down? There were no billboards. It felt so sterile to me. I was so happy to get back to West Berlin because of all the images. The first thing I thought was: ‘Wow! Pictures.’

Now I’ve done this sort of thing in Germany before, but never in Berlin. In Warsaw it will be different. I’m going to do nationalism and reproductive rights. In all of eastern Europe and in the Soviet Union, the nationalism thing is chilling. And of course, in Poland the abortion issue is critical. I would much rather do this sort of thing than be in a big exhibition with all these male misogynist/impresario/art historical curators who hate my work, hate my work. I can’t tell you.

One German curator said to me: “Well, it’s clear that your work comes straight out of Hausmann and Heartfield.” And I said: “Oh, were they doing work on gender and representation?” This is an appropriation of graphic capability enlisted in the struggle of genders. But, of course, he wasn’t thinking of that, because that would have meaning.

First published in Eye no. 5 vol. 2, 1991

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.