Autumn 2011

Bare bones of the revolution

Richard Pare’s photographs of Russian architecture strike up a dialogue with a time of energy and optimism.

For the past fifteen years, photographer Richard Pare has documented Russian Modernist architecture. He had long admired the aesthetics of Modernism – his painter father had introduced him to the works of Mondrian and Picasso, and an art teacher had given lectures on Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe and the Bauhaus. But it was not until 1993 – when a photograph he came across at a friend’s gallery sparked his interest – that Pare started to become more acquainted with the Russian branch of the movement. The photo was of Vladimir Tatlin and his assistants working on the model of the Monument to the Third International, which was unveiled in 1920 in St Petersburg to celebrate the third anniversary of the Revolution. The friend, noticing his interest, invited Pare to accompany him on a trip to Moscow. Pare was surprised at the number of buildings that had survived: ‘The chance to record the range and brilliance of that work, even 70 years after the fact, was an extraordinary opportunity.’

In ‘Building the Revolution’, curated by Mary Anne Stevens of the Royal Academy of Arts (RA) and Maria Tsantsanoglou of the State Museum of Contemporary Art Thessaloniki (SMCA), Pare’s work is presented alongside vintage photographs of the same buildings, as well as Constructivist art of the era. Stevens describes the exhibition as ‘a dialogue between the art and the architecture of the period of 1915 to 1935. It focuses on an incredible period of energy, activity and experimentation.’

While the bold geometric art and carefully composed archive photos illustrate the Socialist ideals of the time, Pare’s images steal the show. He says: ‘The idea was to articulate the poetic vocabulary of Modernism and also to allow the accumulation of time to have a part in the dialogue, to give a depth and richness to the subject that it might not have had when it was built.’

Writing about his experience of wandering in the abandoned Vasileostrovskii district factory kitchen in St Petersburg one afternoon, Pare says, ‘I felt as though the structure had returned to the essence of the architects’ intention; all superfluity had been torn away and what remained was the bare bones of the structure, peeling and crumbling until it revealed the ancient techniques that had been employed in its construction.’

It is tempting to throw the Modernist baby out with the Soviet bathwater. Pare notes that in allowing the buildings to decay, there has been ‘a tendency to see all the works created during those years, in architecture especially, as being bad by definition. I don’t think it is fear so much as blindness, an inability to accept the transformative intention of the visionaries who conceived the radical buildings of the Modernist period.’

Although short-lived, there was a sense of optimism after the social revolution, and a new architectural style was developed to promote the Communist way of life.

‘The paradigms were the communal house and the factory instead of the mansion and the cathedral,’ says Pare. ‘Architects were responding to the opportunities presented by the revolution … before it became suborned all too swiftly.’

‘Building the Revolution’, Royal Academy of Arts, London, from 29 October 2011 to 22 January 2012.

Top: Red banner textile factory: view of the power plant. Photo: Richard Pare, 1999.

Karla Hammer, writer, London

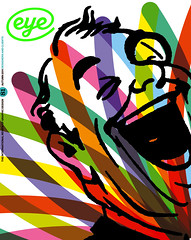

First published in Eye no. 81 vol. 20 2011

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.