Summer 1997

Between histories

The graphic design legacy of the young republic of Croatia can be traced through its turbulent past and rich traditions. By Orsat Francović

At the beginning of the 1990s a violent succession of civil wars shook the Yugoslav federation. Waves of nationalism spread from Serbia to every other area. Communist leaders, unable to deal with the situation, organised a first attempt at democratic elections. Croatia declared its independence. War struck the country bitterly and the world witnessed the bloody results.

Despite this turbulent recent past, Croatian graphic design has a powerful legacy that belies its absence from reference books and histories of the discipline. Croatian Modernism has its roots in the architecture of the 1920s and 1930s, when buildings were erected in Zagreb that could stand comparison with the best achievements of the International Style. After the Second World War, the Communist government of Yugoslavia approved Modernist models for communal housing and complete new towns were built: it began to look like Le Corbusier’s dream.

Ivan Picelj, originally a painter, became one of the founders of the Croatian group EXAT 51, whose manifesto urged a synthesis of all the artistic disciplines, erasing the differences between the fine and applied arts. Over the period 1951-57, the group revolutionised design in Yugoslavia. The principles of Modern art, architecture and design were seen by the public as mainstream achievements. International acknowledgement came in 1957, when Vjenceslav Richter, Boris Babic and Mario Antonini won the silver medal at the international Triennale in Milan for the Yugoslav pavilion’s interior set.

The outstanding designers of that period were Picelj, in the arts, and Milan Vulpe in the field of industry. Though a market economy did not exist, there was certainly a “market” to reach. The Industrial Design Centre (CIO) was founded in Zagreb during 1963-64 with a mission to: “transfer knowledge and experience of the international practice of industrial design…educating people to either create or buy design.” The state body promoted design, linked designers and industries and collected, stored and released information: it initiated many conferences, symposiums and exhibitions, among them the British Design Exhibition in collaboration with the British Council in Zagreb in the late 1960s.

The CIO introduced its first graphic design projects during 1967-68, including a professional analysis of the visual communication of Croatia’s osiguranje (insurance company). After a period of crisis during 1968-70 the body redirected its activities towards graphic design, and in 1971 it was asked to realise the visual identity and standards for Radio Television Zagreb (RTZ). Matko Mestrovic, the head of the communication department, moved from CIO to RTZ for two years to supervise the application of the logo and house style. Mestrovic’s formal title was “the advisor to the Chairman of the RTZ for the questions of visual identity”. His status, and the importance accorded to design within RTZ, was marked by the fact that his office was next door to the chairman’s.

All Croatian designers are educated formally at the Fine Art Academy of the Faculty of Architecture. Architects, designers and painters who had played leading roles in the promotion of Modernism in the 1950s and 1960s recognised the need for specialised design education. As a result, The School of Design (industrial and graphic), was founded in 1989 under the roof of the Faculty of Architecture as an interdisciplinary study where all knowledge and experience, both scientific and artistic, should be combined. The first students graduated in 1994.

At present it is too early to talk about the impact made by the school’s alumni. War has devastated most of the industry, as well as the cultural domain, so there are few signs to mark where Croatian design may be heading. Yet the anticipated period of recovery will mean that the graphic design profession should be engaged more than ever before.

Milan Vulpe

Though many of his contemporaries were concerned with cultural design, Milan Vulpe set his heart on industry. In the period from 1950-59 Vulpe worked for Chromos, a paint manufacturer, to establish the complete visual identity of the company: logo, mascot, packaging and advertising campaign.

He completed the logo, along with the basic applications, in 1953 and finished the mascot in 1954. Using the mascot, a schematic human figure, and putting it in different contexts (and painting almost everything) Vulpe created a series of commercials with a simple colourful articulation made possible through the character of the products. The message was clear and easily understood by the public. Yet the mascot established the ground for unlimited and multifarious exploitation.

One characteristic poster represents a whole range of Chromos’ products with colour areas, each for a different range of Chromos products. Free from unnecessary details, the poster spells out its message loud and clear. By contrast Pliva, the pharmaceutical industry, demanded a different approach from Vulpe. The consumer being addressed was a member of the pharmaceutical or medical profession. Close communication between graphic design and medical experts resulted in good, refined and effective designs.

By using some of the medicine labels and creating humorous visual information, Vullpe created an optimistic air, a belief in cure. He used Rayograms (photographic images drawn by one light source in motion) as well as photograms combined with photographs that foreshadowed the blurred images of computer-made designs of the 1990s.

Apart from his work for Chromos and Pliva, Vulpe created products for a number of clients, including pencil factory TOZ, detergent factor Saponia, the ‘Muzički Biennale Zagreb’ music festival and many more.

Vulpe won international recognition with awards including Premio Europeo Rizzoli 1965 and The Gold Medal, Monde Selection, Paris 1967.

Ivan Picelj

Picelj, a leading figure in Croatian post-war design, developed a conceptual view of graphic identity that veered towards the status of pure signs, His logotypes make a stark contrast with the symbolic, stereotypical solutions of his communist surroundings. He designed more than 500 posters and became the central figure in Croatian poster production. Apart from the psoters he made for EXAT 51, which he co-founded, Picelj co-operated with a number of institutions on ‘cultural posters’ made principally for exhibitions. The main characteristics of his work were defined in the manifesto of EXAT 51: ‘Working methods and principles in the domain of non-figurative art, e.g. abstract art, are not the expression of decadent aspirations. They provide the possibility that, by studying those methods and principles, one can develop and enrich the field of visual communication.’

Picelj applied these principles in his paintings and designs with an almost religious devotion. There is nothing haphazard or ‘artistically spontaneous’ in his work: he exerted full control over every step of the production process.

He made a series of posters for Museum of Arts and Crafts (MUO), and collaborated with the Gallery of Modern Art, the Gallery of Contemporary Art and the Chamber of Printed Arts of YAZU (Yugoslavian Academy of Arts and Sciences) in Zagreb and Gallery Denise Rene in Paris. Picelj formed his own structures, with elements from abstract, geometrical experiments that used the smallest amount of visual information necessary to recognise the exhibitor, together with simple type solutions.

Picelj was also one of the founders and active members of Nove Tendencije (New Tendencies), 1961, the international art movement based in Zagreb.

Mihajlo Arsovski

Mihajlo Arsovski established his reputation as the graphic designer for Pop Express and the student magazine Polet, but the most significant (and also the largest) part of his opus was the work he did in collaboration with the Student Centre in the 1970s for the ITD Theatre. He established a design icon for the company, making more than 100 posters, leaflets and postcards for different theatre productions.

‘Considering the character of those plays, one could easily say that the theatre found the ideal designer in Arsovksi. Just as those bold productions and plays were representing consciousness of theatre experiments…the visuals of the house designer were the best of Modernist graphics, altered according to the spirit of time, still vibrating with the remnants of 1960s optimism.’ (from Mihajlo Arsovki – king of Croatian typography’, by Feda Vukić, Vidi magazine no.1)

Arsovski used letters as a pictorial element, and created highly poetic typographic images. His poster for Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead stands out from the many he made for ITD theatre. Playing a game with the viewer, Arsovski turned the title of the play into a mathematical equation.

Boris Ljubičič

During the 1980s and 1990s Ljubičič’s name has become synonymous with contemporary design in Croatia.

He had joined the CIO at the time of the big Radio Television Zagreb (RTZ) project in the early 1970s, and in 1976 won the competition for the logo of the Mediterranean Games (RTZ ’79) to be held in Split in 1979. Ljubičič, as art director, headed the ‘Team of Visual Communications – CIO’ with Stipe Brčič and Rajna Buzič as designers and co-ordinators of associated projects.

Officials expected that the logo would be based on the usual logo of the games containing three standardised circles (like the ones of the Olympic Games) ‘decorated’ with some local elements. Ljubičič did exactly the opposite, changing the sacred circles by dipping them into the Mediterranean sea with no intention of adding anything to them. After the Mediterranean Games in Split, General Comity decided to adopt this symbol as the permanent logo for the Games to come. The team realised several more projects until Ljubičič left at the beginning of the 1980s to form his own Studio International.

In the war period of the early 1990s Ljubičič created exceptional posters. Krvatska is based on a word game. In the Croatian language the word Hrvatska means Croatia and the word krv means blood. Substituting the first letter of the word and displaying the word in three lines he formed the statement that clearly denoted the time and place where he lived. Another outstanding war poster played with the meaning of the expression ‘–Read between the lines’. Those huge, widely spaed words tempt the viewer to come close and see what is between the lines. There, in small print, is an account of the tragic destiny of the town of Vukovar.

Ljubičič defines the 1990s as a time that is predominantly politically motivated and explains the lack of experimentation in Croatian design thus. ‘Experiment exists only in the political context of forming information. It is not Krvatska, it should be Hrvatska etc. Design is not free communication any more, it is trapped by politics and defined by its final targets.’

Darko Fritz and Zeljko Serdarević

Darko Fritz and Zeljko Serdarević (or Imitations of Life Studio), started their collaboration with the Eurokaz Festival of New Theatre in Zagreb. From 1987-96 they produced twelve posters for this festival. Fritz explained his work as a ‘recycling’ of visual material, saying: ‘Why should we produce new images if there are so many good old ones.’ In all his works, the sources of recycled images are anonymous. Only in the poster series for Eurokaz are there references to original sources. This imagery was transplanted from the 1920s and 1930s theatre avant-garde, forming a design statement on contemporary theatre avant-garde that was promoted by Eurokaz.

Like Ivan Picelk, his spiritual father in some respects, Fritz brought his fine-art experience to graphic design and vice versa. He defined the form of the theatre poster as the ideal medium for using visual elements from different milieus. ‘If you create a poster for the 500th production of a play, you are free to formulate information without obligation to the narrative because there is some sort of pretext, but if you are doing a company logo, you have to produce a new identity. That is an obligation which kills your creative freedom,’ wrote Fritz.

They designed another series of posters for the drama company of the Slovenian National Theatre in Maribor by placing two large sheets on top of each other for each poster. At the bottom was a black area with all the information about the play but the reminder was a huge image.

The Eurokaz 1992 poster is somehow prophetic. The combined use of three fluorescent and one metallic colour produced a toxic, aggressive impact. Constant experimentation produced many interesting results. Their ‘Eastern Dance – Goes Emotional’ poster, printed in four colours, form a hologram effect, with the illusion of a subjectively moved image. The first image, printed in blue and then hidden under black, overlaid with a silver printed image, is perceived to move past the viewer.

In recent times, Fritz has introduced type manipulation to his time-art works and minimised it in design works, preferring a simple, purer use of letters.

First published in Eye no. 25 vol. 7, 1997

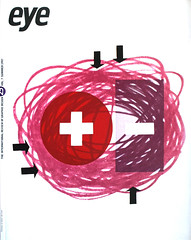

Top. The cover of Eye 25 is a detail from a 1963 promotional poster for pharmaceutical company Plivacombin by Croatian designer Milan Vulpe.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.