Summer 2002

Big subject, little pictures

Joe Sacco uses the comics medium to describe the lives of Palestinians

‘In a world where Photoshop has outed the photograph as a liar, one can now allow artists to return to their original function – as reporters.’ Art Spiegelman.

Originally published in the 1990s as a nine-issue comic series, Joe Sacco’s Palestine is an illustrated account of the Oregon cartoonist’s visit to the Occupied Territories during 1991 and 1992. Focusing on how private lives are affected by public policies, Sacco depicts a retaliatory loop of routine horror, while navigating the region’s infernal history and political sensitivities. Now republished in a single 290-page volume with a new introduction by the critic and historian Edward Said, Palestine remains, in the light of recent events, as pertinent as ever. With luck, the graphic novel format will afford some measure of contact with booksellers beyond the ghetto of specialist comic stores and introduce Sacco’s work to the wider audience it undoubtedly deserves. (Palestine has, at the time of writing, already sold more than 20,000 copies in book form.)

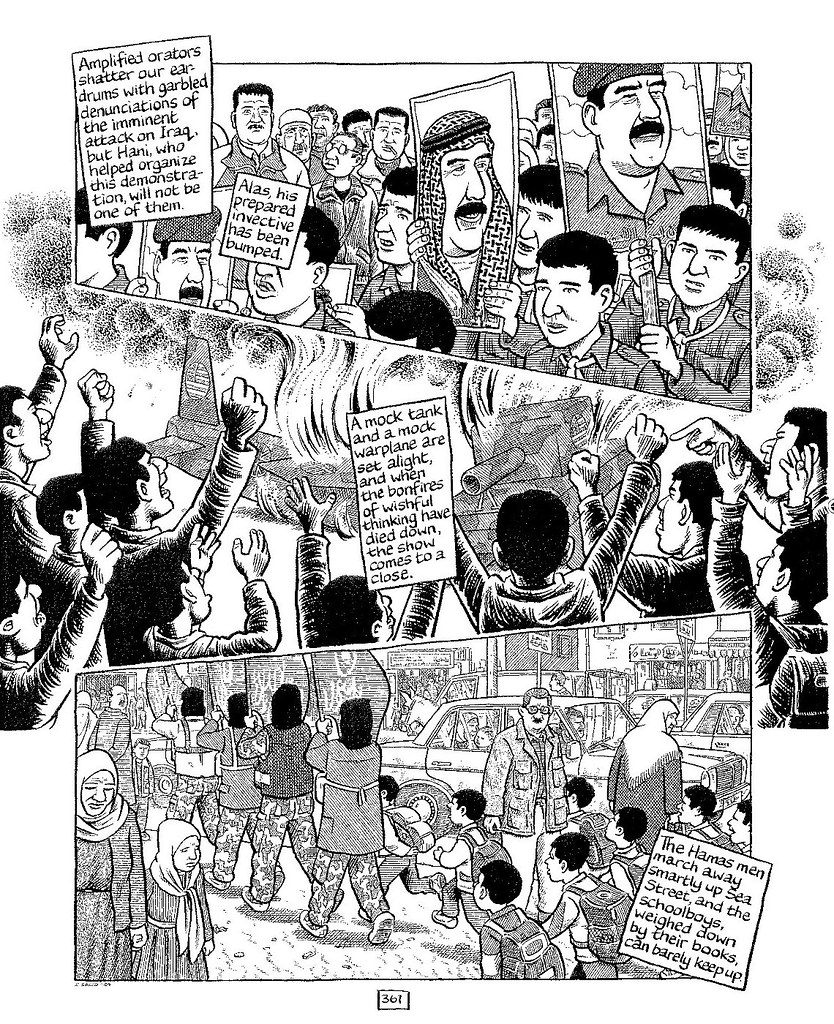

Drawing on first-hand experiences, extensive research and over 100 interviews with Palestinians and Jews, Sacco has gained access to unusually intimate testimony and given space to details and perspectives normally excluded by mainstream media coverage. The enthusiasm and frequency with which Sacco is hauled into the homes of those he meets – to listen, take notes and drink endless amounts of tea – underlines the desperation of the people he encounters; their hopes are pinned not on political promises, but on telling their stories to a stranger who writes comic books. Although the critical response to Palestine has been overwhelmingly positive, a number of stridently Zionist websites have, perhaps inevitably, accused Sacco of ‘Jew bashing’ and Sacco’s Seattle publisher receives the occasional piece of hate mail. Yet Palestine is a remarkably even-handed work, humanist in tone: ‘And if I’d guessed before I got here and found with little astonishment once I’d arrived, what can happen to someone who thinks he has all the power, what of this – what becomes of someone when he believes himself to have none?’

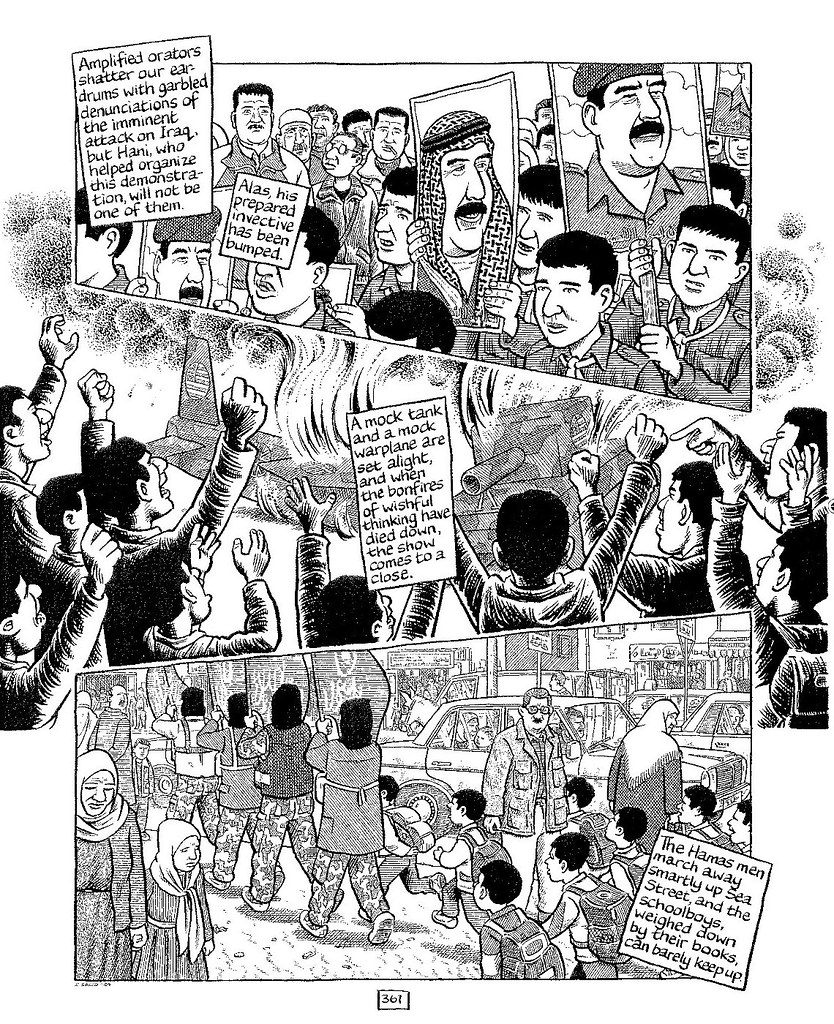

The original Palestine comic series won the 1996 American Book Award and Sacco’s eyewitness illustrations have since been exhibited across the us. (Time magazine favourably compared Palestine with Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer prize-winning Maus, an anthropomorphic account of the Holocaust. However, while both titles employ the cartoon form to heighten impact and engagement, Sacco’s work is the more nuanced and sophisticated of the two.) The book’s fluid imagery – described by one critic as ‘endless mud and obsessive cross-hatching’ – is memorably atmospheric and faithful to the landscapes and cities of Palestine. It also evokes an almost surreal routine of bureaucratic harassment, roadblocks and tear gas, punctuated only by moments of mordant humour. Despite the careful characterisation of those around him, Sacco’s cartoon self is slightly unreal – a grotesquely exaggerated figure, complete with enormously elastic lips – a formlessness that, rather curiously, invites identification. However, Sacco’s draughtsmanship is perhaps best demonstrated by his complex crowd scenes, with their differentiated faces, pointed detail and disjointed snippets of overheard speech and interior narrative.

Although Palestine is both visually engaging and a labour of artistic love, at its heart lie a commitment to hard-edged journalism and a challenge to the notional objectivity of the Western (and particularly American) media: ‘I came from the standpoint of “Palestinian equals terrorist”. That’s what filtered down in the course of watching the regular network news …’ Sacco makes no pretence of the observer’s invisibility and depicts his own initial disbelief of reported detentions and torture. Nor does he shy away from revealing his own ambivalence as a visiting Western journalist. (As a street demonstration threatens to erupt into violence, we see Sacco bolstering his confidence by repeating to himself: ‘It’s good for the comic, it’s good for the comic …’ ) By the time of this volume’s publication, nearly a decade since the first comic, Sacco’s viewpoint has been focused by experience. In a new introduction, he writes: ‘Through the long-term strangulation by Israel of the Palestinian economy, the lives of Palestinian workers and their families have been made even more wretched than they were when this work was first published. One must add the mismanagement and corruption of the Palestine Authority into the unfortunate mix … The Palestinian and Israeli people will continue to kill each other in low-level conflict or with shattering violence – with suicide bombers or helicopter gunships and jet bombers – until this central fact – Israeli occupation – is addressed as an issue of international law and basic human rights.’

With Palestine, as with his other major work Safe Area Gorazde, Sacco has assumed the unlikely role of the pre-photography war artist, while fruitfully exploiting the narrative and textual devices of the comic book. Others have employed the comics form to tell political, non-fictional or biographical stories – among them Steve Darnall, Peter Kuper and Ho Che Anderson – but Sacco’s work is unique in its scale and ambition. Approaching such daunting topics with a disreputable and supposedly juvenile medium may seem futile, even absurd, yet Sacco’s greatest achievement is to have so poignantly depicted contradiction, oppression and horror in a form that manages to be both disarming and disquieting. Palestine not only demonstrates the versatility and potency of its medium, it also sets the benchmark for a new, uncharted genre of graphic reportage.

Joe Sacco, Palestine.

David Thompson, writer, Sheffield

First published in Eye no. 44 vol. 11 Summer 2002

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.