Autumn 1993

Books in freefall

Shinro Ohtake is a master of the artist’s book. His latest is a collaboration with Vaughan Oliver

Years before the publication in 1986 of his first self-designed book, London / Honcon 1980, the Japanese artist Shinro Ohtake had demonstrated his commitment to the printed page in his voracious use of printed ephemera as material for collages recording the bewildering variety of cross-cultural visual sensations that captured his attention. His feeling for books as material objects and as art forms in their own right, which has led him to make a highly personal contribution to the genre known as artists’ books, was first manifested in the dozens of densely layered scrapbooks, bulging with the flotsam of modern life, that he had begun to make in 1977 while still in his early 20s. In this continuing series, created for his own private enjoyment rather than for sale, he has laid bare his roots in Dada and Surrealist collage, with Kurt Schwitters as the guiding light, and above all in Pop Art, which had served as an important stylistic influence on his youthful work. Through Pop he developed a feeling for the visual delights afforded by throwaway mass culture in all its vulgar glory and Kitsch tastelessness. Rivalling Warhol’s acquisitiveness for the trivial and often overlooked artefacts of contemporary culture, from bus tickets to packaging designs, but marshalling them as elements of crowded compositions on collage principles established during the 1960s by such British artists as Eduardo Paolozzi, Ohtake sought to claim as his own every piece of printed design that happened to catch his eye.

As a painter and sculptor, Ohtake has borrowed freely from the works of contemporary European and American artists, seemingly oblivious to the contradictions presented by such varied sources as the student paintings of David Hockney, the ready-mades of Marcel Duchamp, neo-Expressionism and contemplative abstraction. Stylistically, his closest parallel is the work of another plunderer of styles, the German painter Sigmar Polke. By insisting on a fragmentation and dislocation that operates on both a stylistic and cultural level, Ohtake calls attention to the oddness of his situation as a young Japanese artist operating at the edge of Western culture. Looking with a mixture of scepticism and naïve enthusiasm into cultures freely available to him through the mass media, he expresses the predicament of an outsider who can never be sure of fully understanding the mentality of the approaches to which he refers, while at the same time demonstrating the curious freedom of owning no allegiance to the raw material from which he is forging his identity.

Such a blurring of boundaries, with all the creative virtually everyone living in the “developed” countries performs, without giving it much thought, every day. As consumers we are fed an indigestible multicultural smorgasbord. As a matter of course we eat exotic food, watch foreign movies and television programmes, listen to music from other parts of the world and buy products made in other countries. Such contrasts between native traditions and alien influences are far more marked in Japan, where they co-exist in stark opposition rather than blending seamlessly together: the situation is exaggerated by the fact that as a population the Japanese remain fairly sealed off from the rest of the world, while having at their disposal the entire spectrum of international life through technology and commerce. Ohtake, living in Japan but making regular visits to the west, is well placed to an experience in an acute fashion the shocks caused by the collisions between different societies. Paradoxically, the authenticity of his work arises from his willingness to give voice to these ever-shifting definitions of outlook. His art expresses in paradigmatic form the cultural freefall to which we are all subject.

The small-format book 1980, which takes as its subtext the meeting of east and west, set the terms for Ohtake’s subsequent publications, both in the lavishness and intricacy of its production and the wit of its conception. Containing facsimile reproductions of rapid pencil jottings made on visits London and Hong Kong in 1980 and the printed ephemera he collected on the trip, it cunningly calls to mind both sketchbooks and scrapbooks. The limited edition version is particularly successful in conveying the scrapbook quality, containing as it does 200 printed facsimiles of advertisements, comic strips and other souvenirs pasted in on different pages of each of the 300 copies produced. On certain pages of the limited or special edition, strips of sellotape or masking tape are faithfully, but misleadingly, rendered by means of a thick layer of semi-opaque varnish. We are led to question the identity of the material as an illusion for which an appropriate term has yet be devised – trompe-l’ oeil being inadequate to describe its material properties – while at the same time we revel in the sensation of holding in our hands our unique, handmade artefact that conveys an individual’s experience in a poignantly intimate form.

Thanks to such devices and to labour-intensive production, the medium of the printed book, invented centuries ago for the purpose of identical replication, is subverted to give form to a succession of unique objects. The intimacy this brings, in terms of the reader’s relationship both to the material and to the artist, is heralded by the packaging within which each of the books is contained. In the trade edition, a paperback copy of the book sits within a crate-like cardboard case on which is reproduced inside and out a brightly coloured collage of labels and advertisements. The process of unwrapping the case takes on an even more satisfying and ritualistic aspect with the special edition, for which a clothbound box first has to be slipped out of a similarly conceived (but larger and double-layered) cardboard case and then opened to reveal a copy of the hardbound edition, two offset lithographic folded posters in a printed paper wallet and an original etching. As with Ohtake’s more recent books, the elaborate presentation is designed to increase our anticipation, but at the same time to slow us down so that the experience can be savoured. The contrast between the deliberateness with which we have to view the book, and the fast pace of life suggested by its wrappings and contents, is as enjoyable as a moment of contemplation snatched from an otherwise hectic routine.

EZMD, a two-volume slipcased homage to Marcel Duchamp, was published in 1987 by Yobisha Co., Ltd, Tokyo, which had also brought out 1980. One volume, published under the pseudonym Tay Teo Chuan, following Duchamp’s invention of Rrose Selavy as his alter ego, is printed in black and white in the style of a Japanese manga, with subtle intrusions of Duchampian motifs and themes. It is the companion volume, however, which is more compelling. Lusciously printed throughout in full colour, with the full page collages bleeding off the edges, this pays tribute to Duchamp’s aesthetic of the ready-made and makes sly reference to some of his most influential works, as well as to his passion for chess. The perforated shapes cut into several pages, a device more readily associated with greeting cards or children’s books, introduce a playful note and encourage our active participation in the deciphering of the visual drama that unfolds. Given Duchamp’s insistence on the role played by the viewer in completing the creative act, such methods of drawing us into interaction with the book are wholly appropriate. Moreover, the disconnectedness of much of the imagery puts the burden of interpretation firmly on us, although we are left to roam freely through motifs that seem to be surfacing in our consciousness through free association.

Western readers will find Ohtake’s third book, Dreams, published by Yoshiba in 1988, the most impenetrable of his publications, consisting as it does of the artist’s dreams – documented in brief Japanese texts and enigmatic sketches – complemented by facsimiles of snapshots and 100 tipped-in colour reproductions of near-abstract gouaches that hint at half-formed images and give shape to particular moods. In the brief introduction, translated into English, Ohtake writes of the difficulty remembering the events that unfold during sleep and comments tantalisingly on “dreams revisited in the haze of just-waking”. Deprived, however, of the explanations in the accompanying texts, the non-Japanese reader is left to guess not just at the meaning, but at the very identity of the ambiguous forms surfacing in the artist’s memory. The book contains some mysterious and alluring motifs and provides entertainment as a scrapbook diary. Yet on a purely visual level, both as a collection of images and as a book design, it fails to capture my imagination with the same force as Ohtake’s other books.

America II 1989, published in Tokyo in 1989 by the strangely named Sublime of Alfa Cubic Co. Ltd, is an absorbing return to the scrapbook form, printed on a variety of matt and glossy papers with additional printed fragments tipped in to heighten the collage effect. Ohtake had spent the early part of 1989 in the US, travelling to Washington DC, New York, Pittsburgh, Memphis, New Orleans and Santa Fe before settling for some weeks in a studio provided by the Fund for Artists Colonies at Austerlitz, New York. Here he produced nearly 100 suggestive gouaches on paper or canvas, a selection of which he published in 1989 as America in volume I of the Art Random series of monographs published by Kyoto Shoin. Tokens of this gestural idiom appear also in America II 1989, all the pages of which were created between 1 January and 24 March 1989, but the emphasis here, as in the earlier publications, is on the material collected on Ohtake’s travels, as if he had emptied out the haphazardly accumulated contents of his suitcase on to the pages. The effect is as bewildering as the experiences accumulated on a long and hectic journey, as compressed into the rapid-fire monologue of a hyperactive companion on amphetamines, but also as entertaining for the discoveries it offers every time its crowded pages are opened.

Ohtake’s genius for recycling found material, so that we see it as if for the first time, was amply rewarded in the third publication that came out of his American trip: Printed Matter 1989. For this sumptuous book in an edition of only 10 copies, he overprinted images created for the previous booking in a completely random way on abandoned sheets found ready-made during a period of two days at the printing works in Tokyo while the other book was being produced. The intention, as he explained in a text written in February 1990, was to convey his recollections of America from the perspective of a Japanese artist working at a particular moment and under precise conditions in Tokyo. The sense of delirium sometimes occasioned by misprints, for which he had developed a taste through his apprenticeship in Pop Art, is here carried to a heady extreme, with images glimpsed dimly through other images.

The most ambitious and elaborate of Ohtake’s books is Echo 1-100, published in 1991 by UCA, Tokyo in a limited edition of 100 copies. All the elements with which he had previously experimented are here brought together, as befits a boxed set that includes, as its centrepiece, a copy of a massive 356-page retrospective book about his work as an artist in every medium: SO: Works of Shinro Ohtake 1955-91. The insistence on uniqueness here reaches an improbable level. The cover of every copy of SO is hand-drawn with blue ink on white cotton duck; each set contains an original photo-drawing, drawn in ink over a colour reproduction of one of the artist’s paintings; each of the epoxy resin boxes in which the contents are held is a unique three-dimensional collage made by sandwiching layers of printed material between two layers of thin cloth embedded into the mould.

The process of unwrapping the outer layers to discover the contents is also more complex than ever. On removing the outer cardboard box, one discovers a bright coloured Boy’s Festival bag – a commercial object bought ready-made – within which the resin box is held. Inside that are a variety of items that could keep one busy for weeks: a double-sided, fold-out printed collage with interlaced strips threaded through in the manner of basketwork; a folder labelled “Printed Matter 1991” containing a bewildering array of postage stamps, labels, snapshots and other ephemera in facsimile form, printed to the original scale; a packet with EZMD, a CD of Duchamp speaking and a flexidisc of a live recording made in 1985 at the Museum of Modern Art Oxford by Ohtake and Russell Mills; a copy of Shipyard Works 1990, a publication about Ohtake’s fibreglass and resin-boat structures of that year, which gives a clue as to the origins of the procedure borders on insanity, as Ohtake and Kyoichi Tsuzuki, the editor with whom he collaborated on this project, cheerfully admit. It is an extraordinary tour de force.

The appreciation that prefaced the catalogue to Ohtake’s first one-man show, at the Galerie Watari in 1982, was written by David Hockney, whose work had set Ohtake an example as a young student. It was Hockney, too, who claims to have suggested to him that he promote his work through books. These publications have certainly enabled Ohtake to reach a far broader international public than his paintings, sculptures or prints could have, given the expense and logistics of framing, packing and shipping such objects from the other side of the world. It is striking, however, that only one component of all these publications – SO – has served to document his other work. Faithful to the premise of artists’ books, his publications exist in their own right and are exploited for their particular qualities, bringing the artists’ sensibility to bear in the most personal ways for this most intimate of formats. These stunning and innovative publications, which remain among Ohtake’s most original achievements, provide persuasive evidence of the potential of the book as a rich artistic medium.

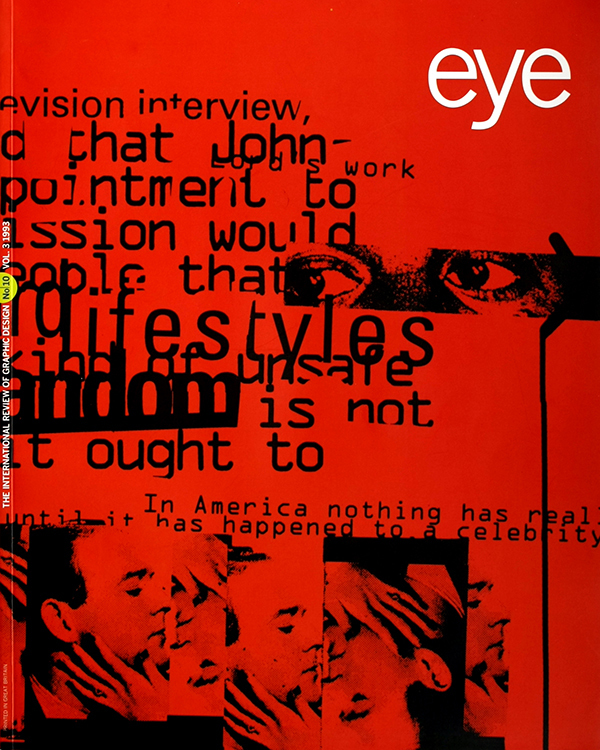

First published in Eye no. 10 vol. 3, 1993

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.