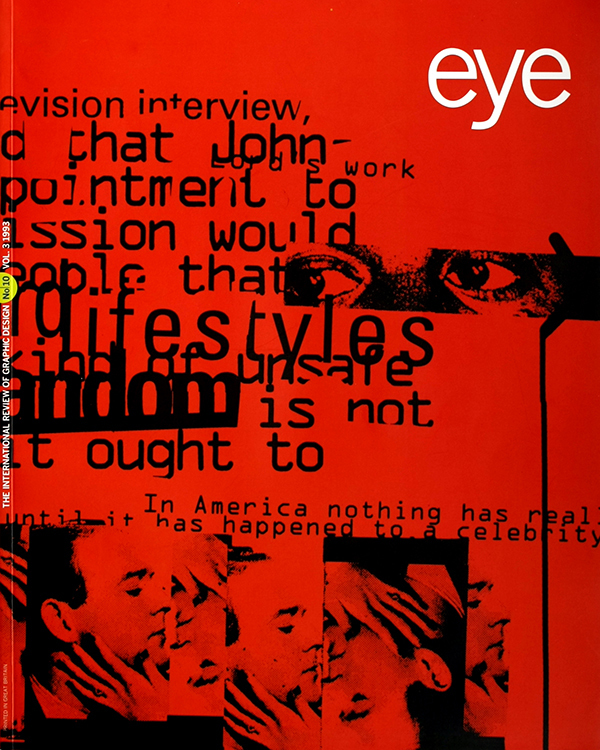

Autumn 1993

Born modern

Painting is dead, long live the dustjacket. Alvin Lustig brought modern art into American bookshops

Alvin Lustig believed that painting was dead and that design would emerge as a primary art form. In his poetic book covers of the 1940s, he remade the visual languages of Dada, the Bauhaus and Surrealism.

The history of graphic design is replete with paradigmatic works – as opposed to merely interesting artefacts – that define the various design disciplines and are at the same time works of art. For a design to be so placed, it must overcome the vicissitudes of fashion and be accepted as an integral part of the visual language. Such is Alvin Lustig’s 1953 paperback cover for Lorca: 3 Tragedies. A masterpiece of symbolic acuity, compositional strength and typographic ingenuity, it forms the basis of many contemporary book jackets and covers.

The current preference among American book jacket designers for fragmented images, minimal typography and rebus-like compositions must be traced directly to Lustig’s stark black and white cover for Lorca (which is still in print) – a grid of five symbolic photographs tied together through poetic disharmony. This and other distinctive, though lesser known, covers for the New Directions publishing house transformed an otherwise realistic medium – the photograph – into a tool for abstraction though the employment of reticulated negatives, photograms and set-ups. New Directions publisher James Laughlin hired Lustig in the early 1940s and gave him the latitude to experiment with covers for the New Directions non-mainstream list, which featured authors such as Henry Miller, Gertrude Stein, D.H. Lawrence and James Joyce. While achieving higher sales was a consideration, Lustig believed it was unnecessary to “design down” to the potential buyer.

Lustig’s approach developed from an interest in montage as practised by the European Moderns of the 1920s and 1930s. When he introduced this technique to American book publishing in the late 1940s, covers and jackets tended to be painterly, cartoony or typographic – decorative or literal. Art-based approached were considered too radical, perhaps even foolhardy, in a marketplace in which hard-sell conventions were rigorously adhered to. Unlike in the recording industry, where managers regarded the abstract record covers developed at about the same time as potential boost to sales, most mainstream book publishers were reluctant to embrace abstract approaches at the expense of the vulgar visual narratives and type treatments they insisted captured the public’s attention.

Lustig rejected the typical literary solution of summarising a book thought a single, usually simplistic, image. “His method was to read a text and get the feel of the author’s creative drive, then to restate it in his own graphic terms,” wrote Laughlin in Print in October 1956. Although mindful of the fundamental marketing precept that a book jacket must attract and hold the buyer’s eye from a distance of as much as 10 feet, Lustig entered taboo territory through his uses of abstractions and small, discreet titles. His first jacket for Laughlin, a 1941 edition of Henry Miller’s Wisdom of the heart, eclipsed previous New Directions titles, which Laughlin described as jacketed in a “conservative, ‘booky,’ way”. At the time, Lustig was experimenting with non-representational constructions made from slugs of metal typographic material that reveal the influence of Frank Lloyd Wright, with whom he briefly studied. Though Wisdom of the Heart was unconventional for the early 1940s, Laughlin was to dismiss it some years later as “rather stiff and severe…It scarcely hinted at the extraordinary flowering which was to follow.”

Laughlin was referring to the New Directions New Classics series, designed by Lustig between 1945 and 1952. With few exceptions, the New Classics titles appear as fresh and inventive today as when they were introduced almost 50 years ago. Lustig had switched from typecase compositions such as his masterpiece of futuristic typography, The Ghost in the Underblows (Ward Ritchie Press, 1940), to drawing distinctive symbolic “marks” which owed more to the renderings of his favourite artists, Paul Klee and Joan Miro, than to any accepted commercial art style. Indeed, Lustig was a sponge who borrowed liberally from painters he admired. He believed that after Abstract Expressionism, painting was dead, and design would emerge as a primary art form – hence his jackets were not only paradigmatic examples of how Modern art could successfully be incorporated into commercial art, but showed other designers how the dying (plastic) arts could be harnessed for mass communications. He also believed that the book jacket should become the American equivalent of the glorious European poster tradition, and so used it as a tabula rasa for the expression of new ideas.

Each of Lustig’s New Classics jackets is a curious mix of expressionistic and analytical forms which interpret rather than narrate the novels, plays or poetry contained within. For Franz Kafka’s Amerika, he used a roughly rendered five-pointed star divided in half by red stripes, out of which emerge childlike squiggles of smoke that represent the author’s harsh critique of a mythic America. Compared to an earlier jacket by montagist John Heartfield for the German publisher Malik Verlag, which shows a more literal panorama of New York skyscrapers, Lustig’s approach is subtle but not obtuse. For E.M. Forster’s The Longest Journey, Lustig formed a labyrinthian maze from stark black bars; while the jacket does not illustrate the author’s romantic setting, the symbolism alludes to the tension that underscores the plot. “In these as in all Lustig’s jackets the approach is indirect,” wrote C.F.O Clarke in Graphis in 1948, “but through its sincerity and compression has more imaginative power than direct illustration could achieve.”

The New Classics design succeeded where other popular literary series such as the Modern Library and Everyman’s Library, with their inconsistent art direction and flawed artwork (including some lesser works by E. McKnight Kauffer for the Modern Library), failed. Although each New Classics jacket has its own character, Lustig maintained unity through strict formal consistency. Yet at no time did the overall style overpower the identity of the individual book.

Lustig was a form-giver, not a novelty-maker. The style he chose for the New Classics was not a conceit but a logical solution to a design problem. This did not become his signature style any more than his earlier typecase compositions: using the marketplace as his laboratory, he varied approaches within the framework of Modernism. “I have heard people speak of the ‘Lustig Style,’” wrote Laughlin in Print, “but no one of them has been able to tell me, in fifty words or five hundred what it was. Because each time, with each new book, there was a new creation. The only repetitions were those imposed by the physical media.”

This creative versatility is best characterised in the jacket for Lorca: 3 Tragedies, one of the many covers for New Directions that tested the effectiveness of inexpensive black and white printing in a genre routinely known for garish colour artwork. Another superb jacket in this suite of photographic work is The Confessions of Zeno (New Directions, 1947), for which Lustig combined a reticulated self-portrait that resembles a flaming face with a smaller-scale image of a doll and coffin. The background is cut in half by black and white bands, with an elegant, wedding-script type (reminiscent of the Surrealist graphics of the 1930s he admired in arts magazines such as View) dropped out of the black portion.

In addition to being unlike any other American jacket of its time (although it looks as though it could have been designed today), The Confessions of Zeno pushed back the accepted boundaries of Modern design. With this and other photo-illustrations (done in collaboration with photographers with whom he routinely shared credit), Lustig reinterpreted and polished the visual language of the Bauhaus, Dada and Surrealism and inextricably wedded them to contemporary avant-garde literature. He was not alone: Paul Rand, Lester Beall and other American Moderns also produced art-based book jackets. But Lustig’s distinction, as described by Laughlin in Print, “lay in the intensity and purity with which he dedicated his genius to his idea vision”. While the others were graphic problem-solvers, Lustig was a visual poet whose work was rooted as much in emotion as in form.

Lustig once claimed that he was “born modern” and made an early decision to practise as a “modern” rather than “traditional” designer. Yet he had a conservative upbringing. Born in 1915 in Denver, Colorado, to a family which he described as having “absolutely no pretentions to culture” (The Collected Writings of Alvin Lustig, 1955), he moved at age five to Los Angeles, where he found “nothing around me, except music or literature, could give a clue to the grandeur that had been European civilization”. He was a poor student who avoided classes by becoming an itinerant magician for various school assemblies. But it was in high school that he was introduced by “an enlightened teacher” to modern art, sculpture and French posters. “This art hit a fresh eye, unencumbered by any ideas of what art was or should be, and found an immediate sympathetic response,” he wrote in 1953 in the AIGA Journal. “This ability to ‘see’ freshly, unencumbered by preconceived verbal, literary or moral ideas, is the first step in responding to most modern art.”

Lustig embraced Modernism and turned his attention to Europe, which further exacerbated his antipathy towards American conventions. “The inability to respond directly to the vitality of forms is a curious phenomenon and one that people of our country suffer from to a surprising degree,” he wrote. Since his first exposure was to art that challenged tradition, he was to find that, “For me, when tradition was finally discovered, and understood with more maturity, it was always measured against the vitality of the new forms; and when it was found lacking, it was rejected.”

Lustig’s introduction to Modernism, his espousal of utopianism and his passion for making magic converged at an early age. He fervently believed design could change the world and began his design career at age 18 while a student at Los Angeles City College. At this time he also took a job (1933-34) as art director of Westways, the monthly journal of the Automobile Club of Southern California. Next he studied for three months with Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesen East. In 1936 he became a freelance printer and typographer, doing jobs on a press he kept in the back room of a drugstore. It was here that he began to create purely abstract geometric designs using type ornaments – what Laughlin termed “queer things with type”. A year or so later he retired from printing to devote himself exclusively to designing. He became a charter member of the Los Angeles Society for Contemporary Designers – a small and intrepid group of Los Angelenos (including Saul Bass, Rudolph de Harak, John Folis and Louis Danzinger) whose members had adopted the Modern canon and were frustrated by the dearth of creative vision exhibited by West Coat businesses.

Lustig was a leader of “the group of young American graphic artists who have made it their aim to set up a new and more confident relationship between art and the general public,” wrote C.F.O Clarke. Yet lack of work forced him to move in 1944 to New York, where he became visual research director of Look magazine’s design department. While in New York he took up interior design and began to explore industrial design. In 1946 he returned to Los Angeles, where for five years he ran an office specialising in architectural, furniture and fabric design, while continuing his book and editorial work. But to hire Lustig, notes his former wife Elaine Lustig Cohen, was to get more than a cosmetic make-over. He wanted to be totally involved in every aspect of the design programme – from business card to office building. Cohen speculates that this need for total control scared potential clients, so the profitable commissions came in erratically and the couple often lived from hand to mouth. In 1951 they returned to New York.

Lustig is known for his expertise in virtually all the design disciplines (he very much wanted to be an architect, but lacked the training). He designed record albums, magazines, advertisements and annual reports, as well as office spaces and textiles. He even designed the opening sequence for the popular animated cartoon series Mr Magoo. He was passionate about design education, and conceived of design courses and workshops for Black Mountain College in North Carolina, the University of Georgia, and Yale. Yet of all of these accomplishments, it is his transformation of both book cover and interior design that lives on today.

While the early Moderns vehemently rejected the sanctity of the classical frame and the central axis, Lustig sought to reconcile old and new. He understood that the tradition of fine book-making was closely aligned with scholarship and humanism, and yet the primacy of the word, the key principle in classical book design, required re-evaluation. “I think we are learning slowly how to come to terms with tradition without forsaking any of our own new basic principles,” he wrote, prefiguring certain ideas of post-modernism. “As we become more mature we will learn to master the interplay between the past and the present and not be so self-conscious of our rejection or acceptance of any tradition. We will not make the mistake that both rigid modernists and conservatives make, of confusing the quality of form with the specific forms themselves.” A book like Thomas Merton’s Bread in the Wilderness (New Directions, 1953), which uses both asymmetrical and symmetrical type composition, should not be seen as a rejection of past verities, but as an attempt to build a new tradition, or in Lustig’s words, “the basic esthetic concepts peculiar to our time”.

Although Lustig’s work appeared revolutionary (an unacceptable) to the guardians of tradition at the AIGA and other book-dominated graphic organisations, he was not the radical his critics feared. His design stressed the formal aspects of a problem, and even his most radical departures should not be considered mere experimentation: “The factors that produce quality are the same in the traditional and contemporary book. Wherein, then lies difference? Perhaps the single most distinguishing factor in the approach of the contemporary designer is his willingness to let the problem act upon him freely and without preconceived notions of the forms it should take.” (Design Quarterly, 1954). Lustig’s covers for Noonday Press (Meridian Books) produced between 1953 and 1954 avoid the rigidity of both traditional and Modern aesthetics. At the time American designers were obsessed with the new types being produced in Europe – not just the Modern sans serifs, but recuts of old gothics and slab serifs – that were unavailable in the US. Lustig ordered specimen books from England and Germany which, like many of his colleagues, he would photostat and either piece or redraw. Rather than being severely Modern, these faces became the basis for more eclectic compositions.

At the same time, Lustig also became interested in, and to a certain extent adopted, the systematic Swiss approach, which perhaps accounts for the decidedly quieter look of the Noonday line. To distinguish these books – which focused on literary and social criticism, philosophy and history – from his New Directions fiction covers, he switched from pictorial imagery to pure typography set against flat colour backgrounds. While the Noonday covers are not as visually stimulating as the New Directions work, they were unique in their context. At the time, the typical paperback cover was characterised by overly rendered illustrations or thoughtlessly composed type. Lustig’s format used the flat colour background as a frame (or anchor) against which various eclectic type treatments were offset. The covers were designed to be seen together as a patchwork. Lustig’s subtle economy was a counterpoint to the industry’s propensity for clutter and confusion.

A study of Lustig’s jackets reveals an evolution from total abstraction to symbolic typography. One cannot help but speculate about how he might have continued had he lived past his 40th year. In 1950 diabetes began to erode his vision and by 1954 he was virtually blind. This did not prevent him from designing: Cohen recalls that he would direct her and his assistants in meticulous detail to produce the work he could no longer see. These strongly geometric designs were “some of his finest pieces”, claimed Laughlin, but were not as inventive as his earlier covers and jackets that in Lustig’s words transformed “personal art into public symbols”.

Lustig died in 1955, leaving a number of uncompleted assignments to be finished by his wife, who developed into a significant graphic designer in her own right. He left a unique body of book covers and jackets that not only stand up to the scrutiny of time, but continue to serve as models for how Modern form can be effectively applied in the midst of today’s aesthetic chaos.

First published in Eye no. 10 vol. 3, 1993

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.