Summer 2003

Bring me the head of Nelson Mandela

Activist; fugitive; prisoner; icon: the evolving face of a famous name

Mandela. For many, the name immediately conjures up the image of an ageing, benevolent elder statesman, a global patriarch whose puckered brow amply suggests the extent of his long walk to freedom. And yet, for a man so widely recognised and iconised, the life story of Rolihlahla ‘Nelson’ Mandela is as much a struggle against the tyranny of invisibility, as it has been one against the hegemony of race and South Africa’s former obsession with the ‘correct’ typology of colour.

‘Prison not only robs you of your freedom, it attempts to take away your identity,’ wrote Mandela in his popular autobiography Long Walk to Freedom (Abacus, 1994). Jailed in 1962 for his underground political activities, and sentenced to life imprisonment for treason in 1964, the apartheid government used every mechanism at its disposal to erase the memory of this once prominent – and highly visible – young lawyer / politician. His writings were banned; his image outlawed.

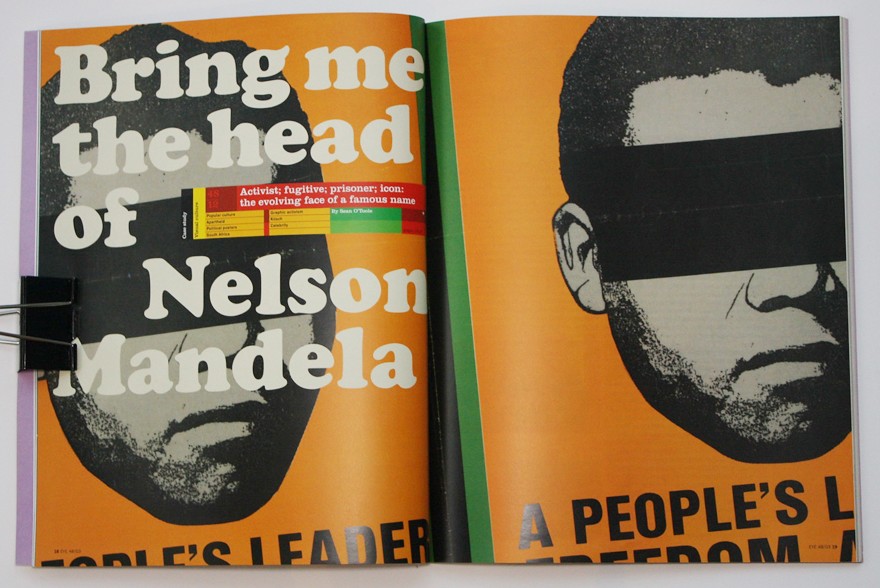

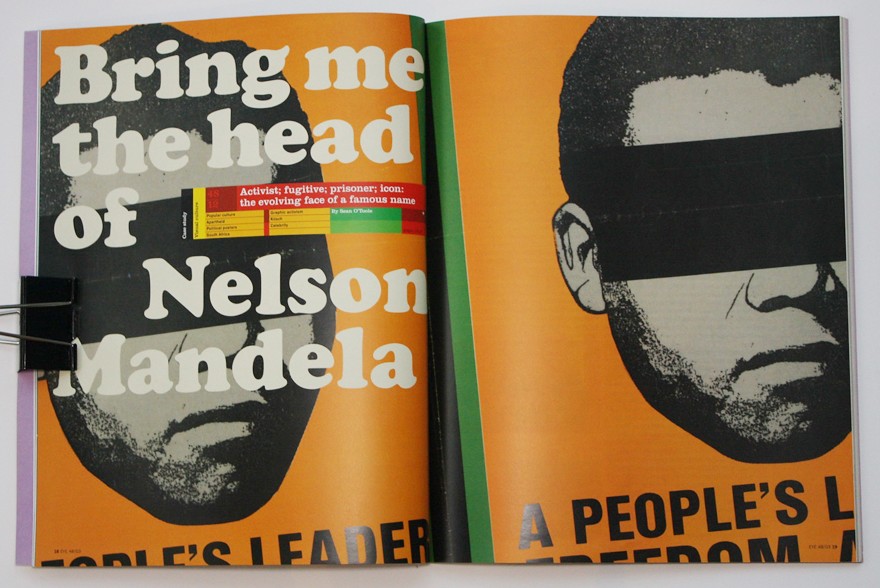

So for many of the 27 years Mandela was in jail, his image was forbidden to all South Africa media. ‘We grew up in a society devoid of pictures of the man,’ explains Sam Raditlhalo, a university teacher with an interest in Mandela’s iconic status. ‘When a picture of Mandela did appear it was made sinister and soulless by the censor’s ink strip across his eyes.’ This crisis of visibility however did nothing to deflate his power, a badly executed anti-apartheid poster of Mandela evoking deep-seated emotions in the popular imagination. ‘He reverberated in our consciousness every single time we marched to confront the police in the township schools,’ recalls Raditlhalo.

I first encountered Mandela’s image during the turbulent late 1980s when apartheid was breathing its final fatigued sigh. Mandela was announcing himself through an assortment of imprecise images. Campus newsletters disseminated badly printed photographs of him dating back to the late 1950s, while suburban walls occasionally featured his stencilled face framed by the exhortation ‘Free Mandela’. On one occasion I came across a tiny photograph of Mandela in the NME [New Musical Express]. The British pop weekly’s masthead must have caught the normally meticulous state censors off-guard. Common to all these encounters was the crude halftone image of a middle-aged man with a light beard and neatly parted hair.

The familiarity of this image was challenged on 11 February 1990, when a benign-looking old man in a suit walked free from prison. For a nation still tentatively emerging from the dark shadow of state oppression, the new television image of Nelson Mandela proved unsettling. An unknown icon was revealed as a real person – someone much older than most of us had expected. Yet despite the incredulity, there was an eagerness to replace the haziness of the past with a new certainty. The image of this seemingly mild old man, always pictured clenching his fist in the air, would quickly become the pivot around which the new South Africa turned and gained its momentum.

Looking back now over the six decades of Nelson Mandela’s tumultuous public life, it is fascinating to note the curious anomalies that mark the graphic interpretation of this most visible of African leaders. Yet throughout his public life, Nelson Mandela’s image has been contested. Outlawed, imprisoned and eventually released, his iconic visage has always been indeterminate, tending towards invisibility, despite his public profile. Today, Mandela’s image is once again the object of official censure, due to the over-zealous appropriation of his image.

The Black Pimpernel

There was a time when Mandela changed his appearance for good reason. Writing of the troubled years prior to his arrest in August 1962, Nelson Mandela commented: ‘Living under-ground requires a seismic psychological shift. The key to being underground is to be invisible. As a leader, one often seeks prominence; as an outlaw, the opposite is true.’ While on the run from state authorities, he often took to disguise. ‘My most frequent disguise was as a chauffeur, chef or “garden boy”. I was dubbed the Black Pimpernel.’ This moniker proved popular with the press (offering a crude adaptation of Baroness Orczy’s fictional Scarlet Pimpernel, who daringly evaded capture during the French Revolution). Later, banished to Robben Island prison by the apartheid regime, Mandela became a ghostly figurehead. By the 1980s, he had become an uncertain icon, a name without the certainty of a definable image: definitely not Che Guevara.

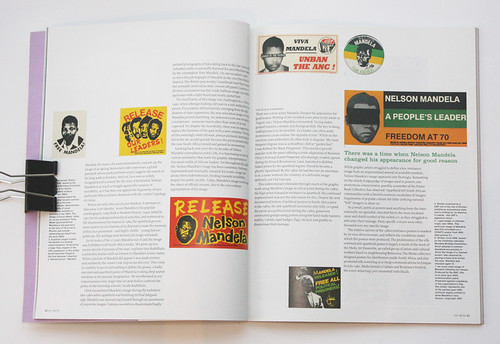

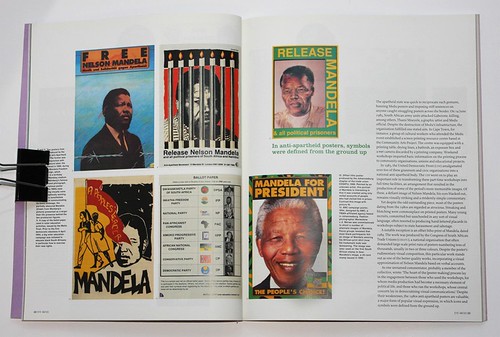

This indeterminacy resonates through much of the graphic work using Mandela’s image as a focal point during the 1980s, the high point of popular resistance to apartheid. His continued imprisonment was not the sole reason for this. Despite the well documented history of political posters in South Africa prior to the 1980s, the anti-apartheid movement only fully co-opted the poster as a political tool during the 1980s, grassroots community groups using posters alongside hand-made banners, leaflets, t-shirts, lapel badges, flags, stickers and graffiti to disseminate their message.

While graphic artists struggled to define a key resistance image from an impoverished arsenal of available symbols, Nelson Mandela’s image appeared only fleetingly. Remarking on the untidy hodgepodge of images used in posters, one anonymous commentator, possibly a member of the Poster Book Collective, has observed: ‘Apartheid left South African communities with a limited common vocabulary of images. Suppression of popular culture left little unifying national “folk” imagery to draw on.’

As a result, political posters used anything from the internationally recognisable clenched fist to the more localised spear and shield symbol of the exiled ANC as they struggled to articulate their message. Party-specific colours were often favoured over any specific image.

The relative naivety of the 1980s resistance posters is marked by its own idiosyncrasies, and reflects the conditions under which the posters were produced. The proliferation of the silk-screened anti-apartheid poster is largely a result of the work of the Medu Art Ensemble, an exiled group of artists and cultural workers based in neighbouring Botswana. The Medu collective designed posters for distribution inside South Africa, and also promoted silk-screening as a cheap communications technique. In July 1982, Medu hosted a Culture and Resistance Festival, the event attracting 5000 interested individuals.

The apartheid state was quick to reciprocate such gestures, banning Medu posters and imposing stiff sentences on anyone caught smuggling posters across the border. On 14 June 1985, South African army units attacked Gaberone, killing, among others, Thami Mneyele, a graphic artist and Medu official. Despite the destruction of Medu’s infrastructure, the organisation fulfilled one stated aim. In Cape Town, for instance, a group of cultural workers who attended the Medu event established a screen-printing resource centre based at the Community Arts Project. The centre was equipped with a printing table, drying lines, a bathtub, an exposure box and a PMT camera discarded by a printing company. Weekend workshops imparted basic information on the printing -process to community organisations, unions and educational projects.

In 1983, the United Democratic Front (UDF) amalgamated over 600 of these grassroots and civic organisations into a national anti-apartheid body. The UDF went on to play an important role in transforming these part-time workshops into full-time facilities, an arrangement that resulted in the production of some of the period’s more memorable images. Of these, a defiant image of Nelson Mandela, his eyes blacked out, remains visually striking and a stridently simple commentary.

Yet despite the odd outstanding piece, most of the posters dating from the 1980s are regarded as atrocious. Streaking and blotching were commonplace on printed posters. Many young recruits, committed but unschooled in any sort of visual language, often resorted to producing hand-lettered placards in workshops subject to state harassment and sabotage.

A notable exception is an offset litho print of Mandela, dated 1989. The work was produced by the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU), a national organisation that often demanded large-scale print runs of posters numbering tens of thousands, usually in two or three colours. Despite the poster’s rudimentary visual composition, this particular work stands out as one of the better quality works, incorporating a visual approximation of Nelson Mandela based on verbal accounts.

As one unnamed commentator, probably a member of the collective, wrote: ‘The heart of the [poster-making] process lay in the engagement between those who used the workshops, for whom media production had become a necessary element of political life, and those who ran the workshops, whose central concern lay in democratising visual communications.’ Despite their weaknesses, the 1980s anti-apartheid posters are valuable, a major form of popular visual expression, in which icons and symbols were defined from the ground up.

Cause célèbre

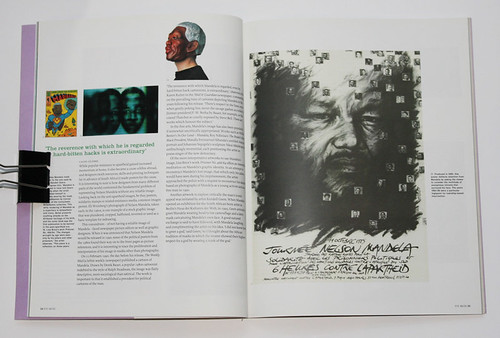

While popular resistance to apartheid gained increased momentum at home, it also became a cause célèbre abroad, and designers (with resources, skills and printing techniques far in advance of South Africa’s) made posters for the cause. It is interesting to note is how designers from many different parts of the world confronted the fundamental problem of representing Nelson Mandela without any reliable image. Looking back on the anti-apartheid images, be they posters, solidarity stamps or related resistance media, common images persist. Eli Weinberg’s photograph of Nelson Mandela, taken early in the 1960s, is one example of a stock graphic image that was plundered, cropped, halftoned, reversed or used as a basic template for redrawing.

This conundrum – of not having a reliable image of Mandela – faced newspaper picture editors as well as graphic designers. When it was announced that Nelson Mandela would be released in 1990, some of the political posters from the 1980s found their way on to the front pages as picture references, and it is interesting to trace the proliferation and interpretation of his image in media other than photography.

On 10 February 1990, the day before his release, The Weekly Mail (a leftist weekly newspaper) published a cartoon of Mandela. Drawn by Derek Bauer, a popular 1980s cartoonist indebted to the style of Ralph Steadman, the image was flatly descriptive, more sociological than satirical. The work is important in that it established a precedent for political cartoons of the man.

‘The reverence with which Mandela is regarded, even by hard-bitten hack cartoonists, is extraordinary,’ observed critic Karen Rutter in the Mail & Guardian newspaper, commenting on the prevailing tone of cartoons depicting Mandela in the years following his release. ‘There’s respect in the lines, even when gently poking fun; never the savage gashes accorded to [former president] P. W. Botha by Bauer, for example, or the crazed Thatcher so cruelly exposed by Steve Bell. These are works which honour the subject.’

In the fine arts, Mandela’s image has also been popularly, if somewhat uncritically appropriated. Works such as Willie Bester’s In Our Land – Mandela, Roy Ndinisa’s The People’s Hero – Black President, Mandla Emmanuel Sibanda’s untitled charcoal portrait and Johannes Segogela’s sculpture Nkosi Sikelele are all unflinchingly reverential, each positioning the artist as praise-singer of the new democracy.

Of the more interpretative artworks to use Mandela’s image, Lisa Brice’s work Prisoner No. 466/64 offers an interesting meditation on Mandela’s graphic identity. In an attempt to reconstruct Mandela’s lost image, that which only his jailers would have seen during his imprisonment, the artist approached the police with a request to reconstruct his identity based on photographs of Mandela as a young activist and as a free man in 1990.

Another artwork to explore critically the man’s iconic appeal was initiated by artist Kendell Geers. When Mandela opened an exhibition for the South African-born artist in Berlin’s Haus der Kulturen der Welt, in 1995, Geers arrived to greet Mandela wearing head-to-toe camouflage and a latex mask caricaturing Mandela’s own face. A good-natured exchange is said to have followed, with Mandela laughing and complimenting the artist on his idea. ‘I did not know how to greet a god,’ said Geers, ‘so I thought about the African tradition of masks in which the wearer showed their highest respect for a god by wearing a mask of the god.’

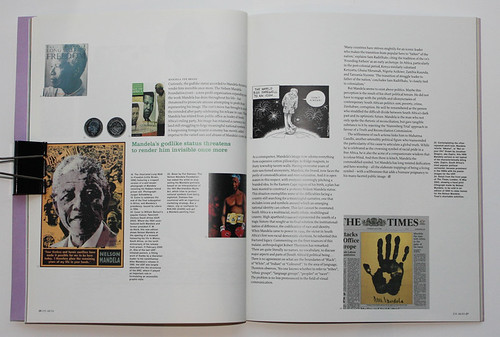

Mandela the brand

Curiously, the godlike status accorded to Mandela threatens to render him invisible once more. The Nelson Mandela Foundation (NMF) – a non-profit organisation expanding upon the work Mandela has done throughout his life – has threatened to prosecute anyone attempting to profit from representing his image. The NMF’s move has brought to an end the extended after-party celebrating his release in 1990. Though Mandela has retired from public office as leader of South Africa’s ruling party, his image has retained a currency in a land still struggling to forge meaningful national symbols. A burgeoning foreign tourist economy has merely added impetus to the varied uses and abuses of Mandela’s iconic face.

As a consequence, Mandela’s image now adorns everything from expensive cotton pillowslips, to fridge magnets, to dusty township tavern walls. Having overcome years of state-sanctioned anonymity, Mandela, the brand, now faces the perils of commodification and over-saturation. And it is open season in this respect, with everyone seemingly pitching a branded idea. In the Eastern Cape region of his birth, a plan has been mooted to construct a 30-storey Nelson Mandela statue. This situation exemplifies some of the difficulties facing a country still searching for a meaningful narrative, one that includes icons and symbols around which an emerging national identity can cohere. This fact cannot be overstated. South Africa is a multiracial, multi-ethnic, multilingual country. High apartheid (1949-90) represented the zenith of a tragic history that sought as its final solution the institutional-isation of difference, the codification of race and identity. When Mandela came to power in 1994, the victor in South Africa’s first non-racial democratic elections, he inherited this fractured legacy. Commenting on the finer nuances of this malaise, anthropologist Robert Thornton has remarked: ‘There are quite literally no names, no vocabulary, to discuss major aspects and parts of [South Africa’s] political being … There is no agreement on what are the boundaries of “Black”, of “White”, of “Indian” or “Coloured”.’ In the area of language, Thornton observes, ‘No one knows whether to refer to “tribes”, “ethnic groups”, “language groups”, “peoples” or “races”.’ The problem is no less pronounced in the field of visual communication.

‘Many countries have striven mightily for an iconic leader who makes the transition from popular hero to “father” of the nation,’ explains Sam Raditlhalo, citing the tradition of the US’s ‘Founding Fathers’ as an early archetype. In Africa, particularly in the post-colonial period, Kenya similarly valorised Kenyatta, Ghana Nkrumah, Nigeria Azikiwe, Zambia Kaunda, and Tanzania Nyerere. ‘The transition of struggle leader to father of the nation,’ concludes Sam Raditlhalo, ‘is closely tied to colonialism.’

But Mandela seems to exist above politics. Maybe this perception is the result of his short political tenure. He did not have to engage with the pitfalls and idiosyncrasies of contemporary South African politics: aids, poverty, crime, Zimbabwe, corruption. He will be remembered as the person who straddled the difficult divide between South Africa’s dark past and its optimistic future. Mandela is the man who not only spoke the rhetoric of reconciliation, but gave tangible substance to it by rejecting the ‘Nuremberg Trial’ approach in favour of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

The selflessness of such actions links him to Mahatma Gandhi, another ostensibly political figure who transcended the particularity of his cause to articulate a global truth. While he is celebrated as the crowning symbol of racial pride in a free Africa, he is also the acme of a compassionate wisdom that is colour-blind. And then there is kitsch, Mandela the commodified symbol. Yet Mandela has long resisted deification and hero worship – all the elaborate trappings of being a living symbol – with a selflessness that adds a humane poignancy to his many-faceted public image.

First published in Eye no. 48 vol. 12 2003

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.