Winter 2017

Firm grasp on a shaky line

R.O. Blechman’s career has spanned illustration, graphic design and film-making. His deceptively simple style masks a fierce intellect

R. O. Blechman’s first book, The Juggler of Our Lady, was published in 1953. Made in a single evening, that book (a graphic novel before the term existed) established a way of working that has remained remarkably consistent over a career now well in to its seventh decade. It is an extraordinary career. A career so wide ranging in its output and achievements that it becomes nigh impossible to summarise. (I would gently urge you to seek out a copy of his 1980 book R. O. Blechman, Behind the Lines, which includes a foreword by his friend Maurice Sendak.) Blechman, known as Bob to his friends, is many things – an illustrator, a cartoonist, a film-maker, a designer, a writer – but above all he is one of the great storytellers.

Blechman’s trembling and unsteady-seeming line is instantly recognisable as his and his alone. It is a gentle style of drawing, tentative and honest, and it can be disarmingly direct. The drawings appear utterly benign and that somehow seems to allow them to sidestep some process within your thinking, a process with which other drawings must negotiate, and affect you emotionally – more directly. It’s a trick of sorts, one that allows a mild-mannered man to get close enough, through sheer benevolence, to wallop you over the head with an idea.

Few storytellers are able to deliver such emotional clout with such simplicity. Fewer still are able to wrap up complicated notions of humour, politics or anger in just a few carefully considered, juddering lines. That economy of line (it is often hard to imagine a way in which his drawings could be reduced any further) only works because the drawings are underpinned by a fierce intelligence.

Almost as unique as the line itself is the fact that a style of drawing so simple and so singular could be so powerfully effective for so long. Sendak noted ‘It is, at first glance, a dangerous style for an artist to lock into. It’s so specific, so special; where can you go from there? Blechman’s refinement of that style – the paradox of his further condensing his miniature hieroglyphs to draw larger meanings – is a marvel.’

The apparent simplicity of Blechman’s work, or rather the assumed ease with which the drawings appear to be created, is deceptive. Each line is scrutinised and deliberated over and, often, done again and again until it is right, until it works. The fact that the drawings then present themselves as effortless little scribbles is one of the more remarkable things about his talent.

When I met the artist and writer Tomi Ungerer in Dublin, his eyes lit up when I mentioned Blechman. ‘Bob is one of the great gentlemen of life!’ he said, raising a glass of red wine. He added later, by phone: ‘Bob measures all of his words. Whatever he says absolutely reflects what he thinks. He is intellectually honest with himself and with the world he lives in … He is a man of integrity.’

On one of my first visits to meet Bob, some time in the spring of 2014, he picked me up from Wassaic train station in a bottle-green ’96 Volvo 940 with license plates that read INK TANK. We drove to his house talking about Saul Steinberg, Robert Brownjohn and the weather – there was a storm coming. On subsequent trips I took a tape recorder with me, but lacked the discipline to make those recordings work as meaningful interviews. I rather enjoyed it when our conversations meandered off to wherever conversations tend to when you’re not worrying about a tape recorder. This interview was, eventually, conducted by email.

Spot illustration for the poem Remaking the Music Box by Geoffrey Hilsabeck, published in The New York Times Magazine, 2017.

Top: Portrait by Maria Spann.

Matt Willey: You were born in Brooklyn in 1930. Tell me a little about some of your early memories.

R. O. Blechman: I was born a year after that great storm, the Depression, struck. But there was no sign of it on East 26th Street, Brooklyn. None. The men all went to work, ties neatly knotted on their shirts, Stetsons set firmly on their heads, the wives setting up tables for their regular games of Mah Jongg, and us kids playing stickball with our homemade bats – broomsticks with their brushes sawed off. No, life was good in our little suburban-like kingdom. The only interruption to our routine was when a long shadow lazily drifted over us, a Zeppelin returning to its home base in New Jersey.

I guess I was taught that I was special. My mother considered me a Blechman, the son of a father who owned a big Dry Goods Store in lower Manhattan (the building now houses Scholastic Publications). At 5pm every day, while the ladies were shouting Buff, Boom, Crack (or whatever those Chinese words were for Mah Jongg), I was dealing with Aleph, Bet, Gimmel, the letters taught in Hebrew School. I was a bad, or I suppose an indifferent, student. Who needed to learn that crazy language? And so I didn’t, not well at least – although once I astonished Miss Berkson when I effortlessly translated a Hebrew passage as if it were a page from Doctor Dolittle.

That seemed to be a pattern in my life, that sudden explosion of energy and creativity. I remember one year in summer camp, I guess I was six or seven years old, I put on a one-person show (Me!) for the entire camp. I promoted it, wrote it, found material for it, put on my own make-up, and then performed it. Solo. All the while, the pennies I had collected for admission, which I had piled on a nearby piano, were rapidly disappearing – taken by a few of the kids. But did I care? You bet your life I didn’t. Not when it was me on that stage, me, dancing, singing, strutting, speaking.

MW: Did you draw as a kid? Were there any early signs of what you would eventually end up doing? Or was there something that you wanted to be when you grew up?

ROB: I had no real interest in drawing, not as a kid. Sure I drew Stukas and Spitfires in dogfights, and sure I copied comic-strip characters, but I did these as much to show off as to amuse myself. I was no Milton Glaser or Edward Sorel who just had to draw, who couldn’t keep their hands off crayons or paint. Not me.

If I was fascinated by any art form, it was film. I built ‘theatres’, shoeboxes where I would turn a handmade crank to move strips of images, hand-drawn or cut from a Sunday newspaper comic, past an open ‘screen’. But did I think of becoming a film-maker? Never. That was beyond my imagining.

Here’s the crazy thing. As a thirteen-year old, now living in Manhattan, I applied to the High School of Music and Art, even though my art teacher in Junior High School refused to write a letter of recommendation for me. And how could she? I was unable to copy photographs from The National Geographic magazine. But I applied, handed in a portfolio, and took the examination.

Months later my mother asked me, ‘Buddy,’ (that was my nickname), ‘Buddy, did you ever hear from that art school?’

‘Yeah.’

‘So what happened?’ (Knowing full well they couldn’t have accepted me.)

‘They took me.’

‘So you’ll go.’

‘I suppose.’

Maybe the reason I applied to art school was my next-door neighbour. She was a young, blonde, very beautiful, very Bohemian, French lady who happened to be an accomplished painter. She had covered every wall in her apartment with scenes of Central Park (we were living in an apartment house facing the park). One of her murals had a donkey painted over a light switch – the switch located in the donkey’s ass. I was sometimes asked to turn the light on. Now if this was art, this was for me!

But did I ever think that I would become an artist? No. That never entered my head, not until college. It was only in college that I began to draw – political cartoons for the college newspaper, occasional posters, a cover for the literary magazine, and once, murals for a school dance – murals that covered every wall of the gymnasium.

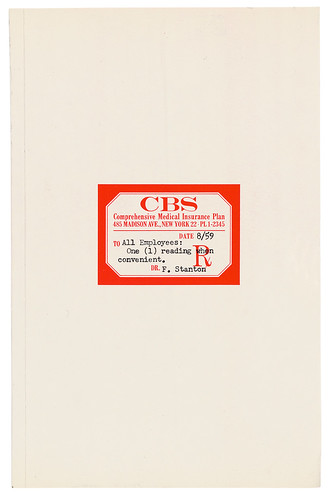

With this 1959 handbook for employees of broadcaster CBS, Blechman made an important but potentially boring official publication (an explanation of the CBS Comprehensive Medical Insurance Plan for eligible employees and their dependents) into a gripping visual narrative, complete with witty information graphics.

MW: I presume The Juggler of Our Lady put you on the map to a certain extent?

ROB: The Korean War (euphemistically termed ‘The Conflict’) was raging, but I was never sent to Korea. That’s a long story, which I’ll go into later. For now, I’ll speak about what happened when I graduated college (majoring in literature and history, with a minor in art history – no studio art classes at all).

My book The Juggler of Our Lady came out in 1953, soon after I graduated college. It received a lot of hoopla – things like a front page write-up in the book review section of a major New York newspaper, The Herald Tribune. I suppose Oxford University Press knew about it because they commissioned me to illustrate an edition of the Broadway play Harvey. As I look at those Harvey drawings now, I shudder. My lines – rigid, lifeless, no character to them at all. I tried different things – sometimes drawing with a pencil, liking the graphite quality that gave me, even adopting Ben Shahn’s stitched line, a look that was then popular among illustrators. Eventually I settled on my now trademark shaky line, a look partly natural, partly contrived. Then the draft caught up with me, and I traded my pen and pencil for a rifle.

MW: I remember you telling me a story about bumping into the designer and illustrator Bob Gill at a bus station, and how that turned out to be a fortuitous chance encounter. Could you remind me what happened?

ROB: Since I was now eligible to get killed in Korea I decided, what the hell, I’d try my hand at selling the cartoons I had done for my college newspaper. That and other work I had done in college, posters, brochures, the not-too-good cover for the literary magazine, things like that. Returning to Manhattan, I was in the Greyhound Bus Terminal when somebody shouted, ‘Stop! Don’t move. Stay there.’ It turned out to be Bob Gill. He was drawing me for his sketchbook.

Gill, as it happened, was a classmate of mine from the High School of Music and Art, somebody I hadn’t seen in four years.

‘Bob,’ I asked him, ‘Why are you doing this drawing?’

‘It’s an assignment. Something for Seventeen magazine.’

When I learned that I asked if I could show him my artwork.

‘Sure,’ he said, handing me his business card (a business card!) ‘Sure. We can meet.’

A day or so later he gave me a list of people to see. One of them was a designer who specialised in book jackets. Soon I met the designer, and because he was connected to publishers I showed him a picturebook I had done for a college seminar in humour. My picturebook, Titus Fortunatus, or Why Rome Fell, was done as the final thesis for the seminar. (Incidentally, I received a B–, the lowest grade in the class, although that B– was shared by one other student, William Goldman, the screenwriter for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid – ironic, as we were the only students in the class who went on to careers in our respective fields.)

The designer suggested that I show my book to an editor at the publishing house, Henry Holt. At Holt, the editor said that he could only publish picturebooks with holiday themes. He probably said this to get rid of me, but that night I called a college friend of mine and asked if he knew of any holiday-related stories. As it happened, he did – a story about a juggler, set in the Middle Ages.

The next night, a copy of Anatole France’s The Juggler of Our Lady in front of me, and a copy of Will Durant’s Age of Faith, next to me for research, I drew the book. And a few days later I surprised the editor by showing up with my version. The book was accepted for publication. Pure luck! If Gill hadn’t been at the Greyhound station on an assignment for Seventeen magazine to draw a young passenger … if that young passenger didn’t happen to be me … if Gill hadn’t been my high school classmate … if Gill hadn’t given me the one name of the one person who knew the one editor who might have been interested in what I had done as a college thesis … if I hadn’t called the one friend who had given me just the right story to draw … etc, etc, etc. You get the picture.

MW: And wasn’t there a story about Bob Gill and Charlie Watts working at the same advertising agency? Then a further connection to Charlie Watts and you a couple of decades later?

ROB: When you ask about Bob Gill and Charlie Watts [of the Rolling Stones] what you’re really asking about is my life in film, so here it is. I had an animation studio for 27 years, The Ink Tank. During that time I managed to produce two 60-minute programmes for PBS [Public Broadcasting Service], a few short films, and dozens and dozens of commercials (and not many of them stupid, either). But my dream project was always to do an animated feature, something that had always eluded me. And at times I came close.

There was the time a friend telephoned me early in the morning. ‘Bob, did you hear NPR [National Public Radio] this morning?’

‘Not at …’ (looking at my alarm clock) ‘… ten before eight.’

‘Well, Charlie Watts was being interviewed. And he said, “I have two heroes in my life. Charlie Parker and the cartoonist, R. O. Blechman, who I hear is still alive and drawing.” ’

That got me up, and fast! When we bought his CD, From One Charlie, we noticed that there was a booklet included in the album, a small graphic novel written and drawn by Watts as a tribute to Charlie Parker. That got me thinking, ‘Why not animate the story?’ So my producer called Watts’s agent, and a meeting was set up in London.

Now here’s the back story. How did Watts learn about me? Before Watts was a member of the Rolling Stones, he was a guy in the bullpen of a small London advertising agency, Charles Hobson (described by Gill, then the agency’s head art director, as a ‘hack agency’ – Gill was never one to mince words). Gill must have shown Watts my book The Juggler of Our Lady. Now Watts and Gill had more than art in common. They were both practising musicians. Gill’s mother was a piano teacher, and Gill himself was an accomplished jazz pianist who, as a teenager, played the Catskills hotel circuit.

Occasionally Gill would play the piano, and Watts the drums, at agency events. And on more than one occasion Gill told me he would tell Watts (real Gill-speak, this): ‘Forget this agency stuff. You’re too dumb to be a designer. You ought to be a drummer.’ And that’s how the Stones got Rolling.

Now here’s how I tried to get my Parker film rolling. I realised early on that Watts’s Charlie Parker story, and his drawings, weren’t making it for me, that I really had to do my own Charlie Parker film, that it had to be with my own drawings. Watts agreed, and I put pen to paper and did a storyboard called Bird in Flight, a double entendre – Parker as a high-flying musician and Parker as an addict. Since Parker was called ‘Bird’ I drew all my characters as animals of one kind or another. Not a bad notion, and one that allowed me to play with reality (something I’d wanted to do, since I had a political agenda about the Kansas City scene that I wanted to utilise).

A few meetings took place that year, maybe two in London, as many in New York, with Watts even mentioning at one point that his friend, Clint Eastwood, might want to get involved. But when Watts, at one of our meetings, asked me: ‘Bob, why do you want me in this film?’ I should have known, poof!, it was all over.

MW: You once told me that you consider yourself a film-maker more than anything else, and that it was with some regret that you were being interviewed as an illustrator. Is that a deep-seated regret?

ROB: Now here’s where I goofed – big time. Here’s where I threw away my chance to become a full time, professionally trained, film-maker, threw away a career-changing, once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. After basic training in the army, I received my MOS [Military Occupational Specialty] which assigned me to a special arm of the military. The arm? The best. The greatest. The most unreal. An assignment to go to film school in New York City. New York, my city, my home. And to learn film. My dream!

So what did I do? (I’m breaking into a cold sweat as I write this.) I turned it down. Flatly. And why? Because I was told that once I finished film school I would be sent to the war zone, not with a rifle, but with a camera. Which was nonsense, of course. And here’s the kicker – I believed it. Sometimes I think God gave me three legs. Two to walk with, one to trip myself up with.

Artwork from Blechman’s 56-minute version of Stravinsky’s L’Histoire du Soldat (The Soldier’s Tale), made by his animation studio The Ink Tank for PBS’s Great Performances series in 1984.

Here’s another instance of that third leg in action. Shortly after having finished my production of Stravinsky’s L’Histoire du Soldat [The Soldier’s Tale], I received a telephone call from a lady with

a heavy German accent. She explained that she was the wife of the late H. A. Rey, the author and illustrator of the Curious George books, a series which I loved, and loved reading to my kids at bedtime. Now she also had a love. She loved, just loved, my treatment of the Stravinsky. Would I consider animating a feature film based on her late husband’s books?

I said no. Now why? Here’s why … After having animated the work of Igor Stravinsky’s soldier, was I going to animate a monkey? Not me. Not when my heart was set on animating a panoramic epic set in ancient Rome, The Golden Ass – a project that ended up with no more than a few minutes of (glorious, as it happened) studio-funded animation. Of course, if I had agreed to animate Curious George, I wouldn’t be stuck in my country home (a hundred long miles from New York City), typing this out. No, I would be reclining by my Hollywood pool. Ouch! That third leg!

MW: Tell me about some of your contemporaries. As well as Gill, it’s a formidable troupe — Robert Brownjohn, George Lois, Seymour Chwast, Tomi Ungerer and so on.

ROB: Tomi Ungerer and I crossed paths often, either in Manhattan or the Hamptons where he had a summer place. Once I saw his summer sketchbook, amazed at the meticulously rendered nature studies – so different from the drawings in his children’s books. He later brought it all together in his paintings for Das Grosse Liederbuch, exquisitely rendered illustrations of songs from his Alsatian childhood.

Every Thanksgiving, Tomi would hold a dinner for his bachelor friends. The dinners were very formal, with finger bowls, crystal knife rests, and hand-drawn place cards. Each card had a drawing of a roast turkey on a platter, its shapely drumsticks sporting ladies’ shoes. Pure Ungerer. I wish I had kept them.

Which reminds me of other cards I never kept – from a neighbour, Andy Warhol. He was then doing illustrations for I. Miller Shoes. His mailings consisted of stylised shoes, each coloured by hand. He drew them using the stitched line of Ben Shahn, then popular with illustrators. As soon as they arrived in my mail I would toss them out. Those cute shoes! Those cute angels and butterflies! Not for me, thank you. Into the trash can they went.

Tomi had a studio on 42nd Street, off Broadway. At the time – the late 1960s – this was a crime-ridden street, the seediest in all of Manhattan. But he had a splendid suite of rooms in a 1920s skyscraper. His two rooms were covered with walnut panelling and the entire fourth floor, his studio, was surrounded by an ornately carved wrap-around stone balcony. Rumour had it that the floor was originally occupied by Florenz Ziegfield (of the Ziegfield Follies).

Every Friday a group of us would meet for a game of basketball. Tony Palladino was a regular, as was Robert Brownjohn (Bj to all his friends, see Eye 04), and occasionally, Bob Gill (Eye 33) and George Lois (Eye 29). We played at a midtown YMCA. Afterwards, we treated ourselves to ice-cream sodas at a corner drug store.

Bj was then at the design agency Brownjohn, Chermayeff & Geismar. One of their clients was Craft Horizons magazine. For the Christmas holiday issue, Bj took sheets of Christmas wrapping paper, and bound them into the magazine. What a wild, crazy, festive, and totally appropriate idea – an actual craft in a crafts magazine! Bj later left for London, one of a large group of American designers who found jobs there. I met Bj in London – this was in 1960, during my European honeymoon. Gone was the rail-thin person I knew in New York. No basketball for him now. Not for a Sydney Greenstreet lookalike.

He briefly returned to the United States, and when we met borrowed $20 from me. Tony Palladino and I were then in a short-lived design partnership, Blechman and Palladino. Bj visited us and gave Tony a large wooden period [full stop], beautifully gilded. He gave me a cracked wooden comma, its gold already flaking. I now no longer have it, but periods and commas have entered more than one of my designs and drawings.

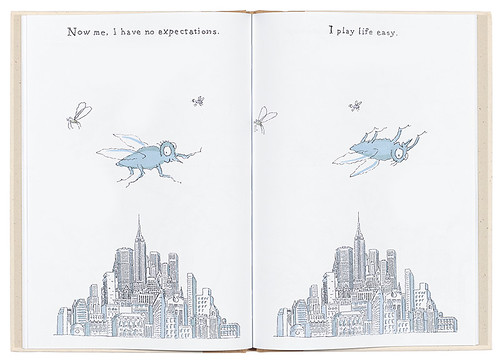

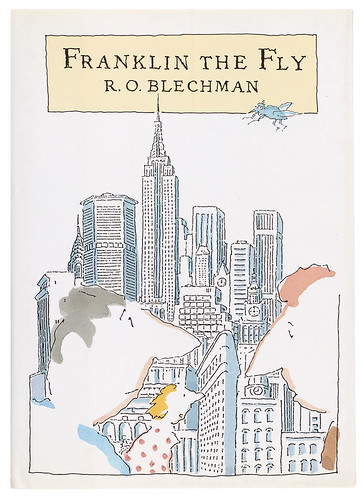

Franklin the Fly, Creative Editions, 2007, is a children’s book about a philosophical fly from New York City. Franklin later saves a country-dwelling butterfly from capture by bothering a net-wielding collector.

MW: And what about Maurice Sendak?

ROB: One of my friends was Maurice Sendak – although, as he once wrote of our friendship, ‘Bob and I are typical colleagues / friends – we hardly see each other …’. I remember meeting him at his home, a brownstone on a tiny Greenwich Village street. His apartment took me aback. This was the early 1950s, and all my friends’ apartments (for those few not living at home) had walls exposed to the brick, and candles stuck in old Chianti bottles. But not Maurice. No, his home had wood panelling, and his furnishings might have been out of a Henry James novel. I later learned that he was a collector of Henry James first editions.

We were both starting out then, and I suppose it was around 1959 that Maurice surprised me by asking, ‘How do I break into advertising?’ I suppose his lifestyle was such that he needed more income than his children’s books provided. Well, I gave him a list of art directors and agencies, but I doubt that he ever assembled a portfolio or even visited a single agency. Soon enough his books caught on and he became a solid citizen on Easy Street.

Our paths crossed professionally in 1972. I was then producing a Christmas special for PBS, and I used one of Maurice’s Christmas cards as the opening sequence. The soundtrack was created by a good friend and marvellous composer, Arnold Black, and I was so impressed when Maurice congratulated him, not merely for the musical setting of his film segment, but for its ‘Schubertian’ sensibility. Schubertian? But Maurice knew his composers. Self-taught, he was no intellectual slouch.We met several years later. I can’t remember the occasion except that Maurice had done a watercolour and wanted my opinion.

‘My opinion? Maurice, it’s fabulous.’

He hugged me. I could not believe that he doubted the worth of that watercolour (it was fabulous). Years later I read something he had said about his work. ‘A little part of me whispers it’s no good.’ I suppose you can leave the shtetl of Brooklyn (as he once described his birthplace, his first language was Yiddish), but the shtetl can never completely leave you.

MW: What pieces of your work are you most fond of?

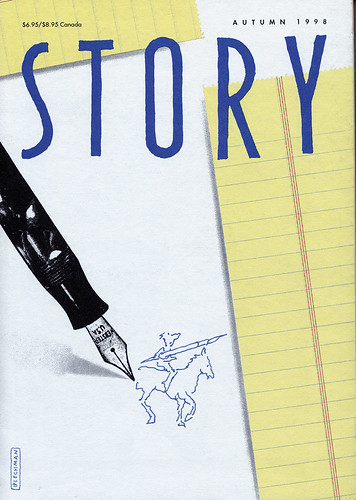

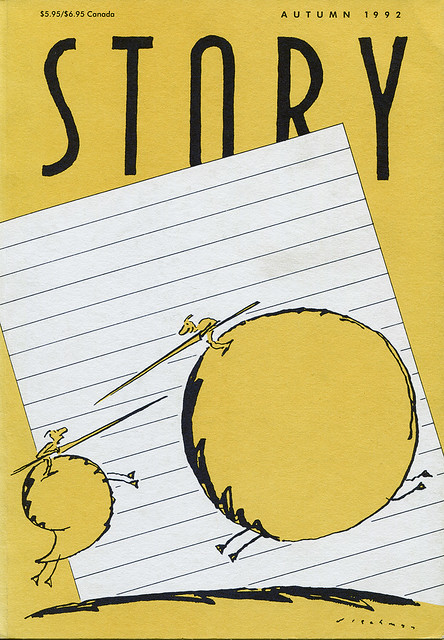

ROB: My favourites go all over the place, ranging from graphic stories to watercolours (my favourite medium). Sometimes I find myself amazed at how good some of them turn out. (‘Did I do that?’) In 1989 I received a telephone call from the publisher of Story, a magazine which was launched in the 1930s, died in the 1960s (the advent of television?), but was revived decades later by an Ohio-based publishing entrepreneur, Richard Rosenthal. His family had founded Portfolio magazine. He asked if he could buy some of my pick-up art to use as a cover for his magazine.

I said, ‘No. I’ll do something original for you.’

‘But I can only give you an honorarium. $100.’

‘I’ll take it.’

Why so quick? Because I love doing graphic design work, a welcome change from illustration.

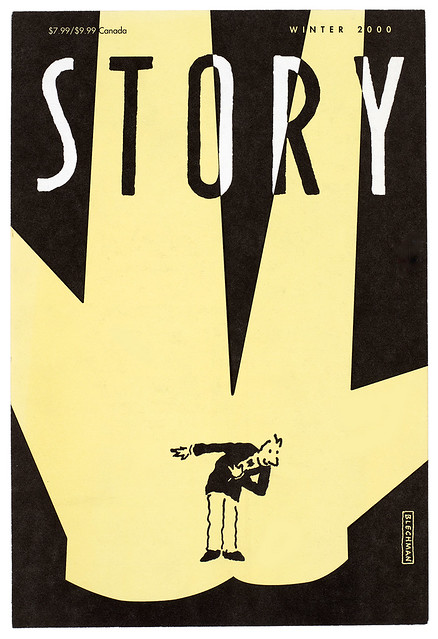

My association with Story began a relationship in which I did every single cover for them – every one – during its ten-year lifespan. Incidentally, in a short while that $100 a cover turned into $1,200, but that was my least reward. My best was working for somebody with a good eye and an open mind.

Moral: if money speaks, sometimes it pays to wear ear plugs.

Fiction magazine Story (originally published from 1931-67) was revived in 1989 by Richard and Lois Rosenthal. Blechman designed every cover from its relaunch to its closure in 1999 with the Winter 2000 issue, above.

Matt Willey, graphic designer, art director of The New York Times Magazine

First published in Eye no. 95 vol. 24, 2018

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. You can see what Eye 95 looks like at Eye Before You Buy on Vimeo.