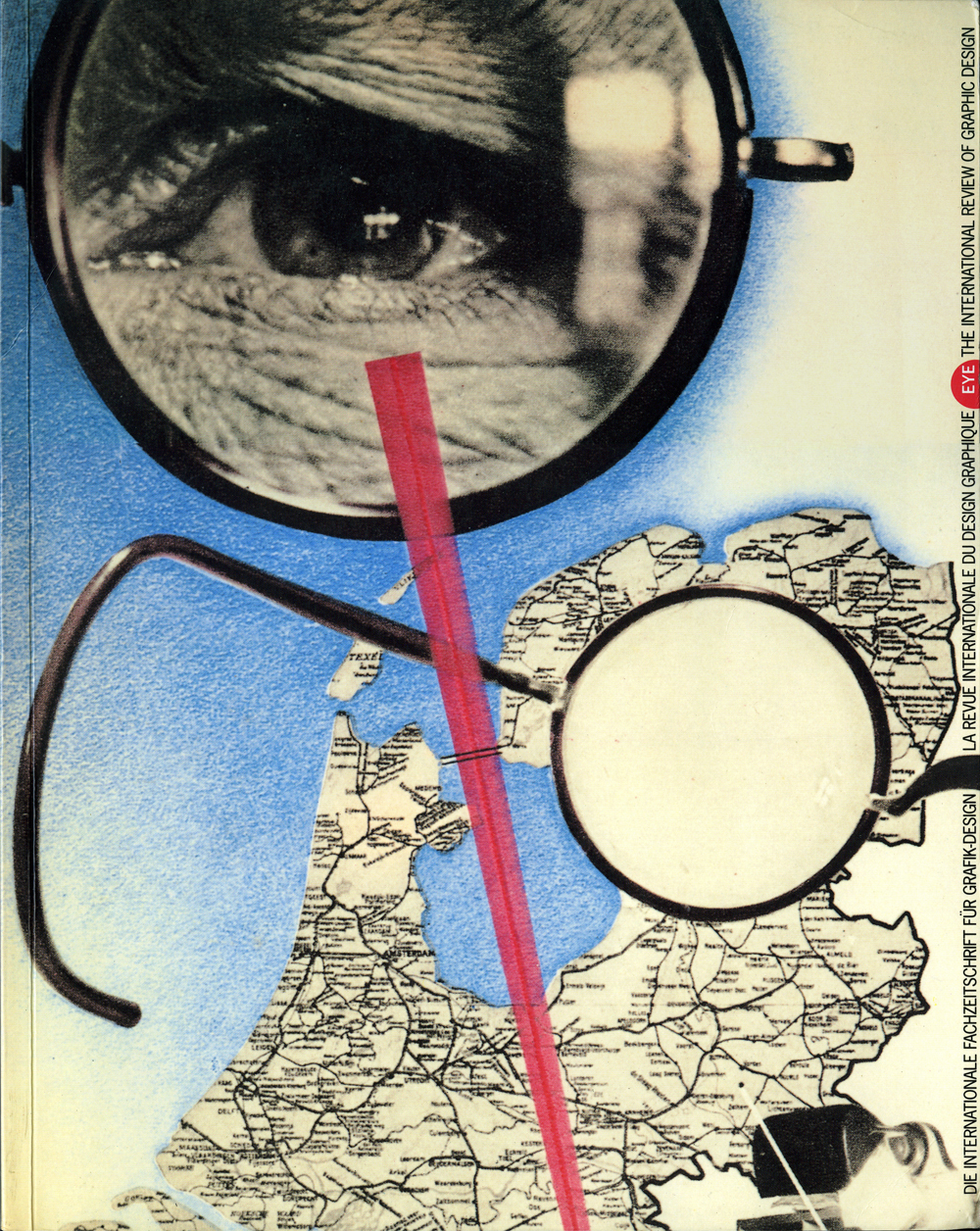

Autumn 1990

Flexible geometry

How Studio Dumbar propelled the PTT into the present

It may not be the most reliable measure of the success of a new corporate identity, but the most stolen canteen crockery in the Netherlands is that of the PTT. No doubt part of the attraction is that it does not explicitly reveal the identity of the company: there are no words and no logo, though the shapes and colours cannot fail to spell out the Dutch postal and telecommunications company to those in the know (and this means everyone in Holland).

The crockery is the most liberated implementation of an identity of remarkable sophistication and subtlety designed by Studio Dumbar to signal the company’s privatisation at the beginning of 1989. ‘The brief for the identity was to reinforce the relation of Post and Telecom to each other and to the PTT holding company, to find a system where the different departments in PTT would be one family, but would be different,’ explains Ada Lopes Cardozo, assistant to Ootje Oxenaar, head of PTT’s in-house art and design department. ‘It had to be based on elements of the old house style: the colours, the Univers type, and the square as a building block.’ These elements were to prove versatile indeed.

The key breakthrough came with what Studio Dumbar staff call the ‘deconstruction sketch’, by Ton van Bragt – the last in a long series of drawings separating, rescaling and layering the elements. Gert Dumbar comments that the design was ‘totally anti-clarity because clarity can be very boring. This brings the new clarity of uniqueness, with dogmatic forms that you can play with in a non-dogmatic way. It’s remarkable what variations other design groups come up with.’

Because the deconstruction occurs from a starting point of grid squares, it is hard for observers not to see something of de Stijl in the patterns that result. Studio Dembar designer Henri Ritxen explains: ‘The logo is built on a grid and the grid has basic forms - the circle and the square. The circle and square elements that you can use in the logo and also away from the logo, for example to position a headline or a photograph or on the side of a building.’

The most closely controlled set of variations occurs in the three logotypes for PTT Post, PTT Telecom and the holding company, PTT Nederland. Each has the letters ‘p t t’ in a modified Univers 65 typeface set in white with a coloured square box. Adjoining the box and separated from it by white rule is another box three units long. Into this rectangle go the division titles and a row of five dots spaced according to the square grid. These are used for registration when affixing subtitles. The dots also hint at the morse of telephony and perforations of stamps.

The boxes are red for the Post, green for Telecom, or blue for the five other divisions. The square box is implicitly divided into a grid of sixteen smaller boxes, three of which are made explicit in the bottom right corner of the Nederland identity, in which small red and green ‘signal boxes’ serve as a reminder that the Post and Telecom are important constituents of the PTT. A third white box is also bitten out of the PTT square - a hint of the deconstructions possible in other circumstances.

In the case of the Post logo, the green box disappears and the red one is replaced by a blue box to indicate that Post is still a part of PTT Nederland. The equivalent happens with the PTT Telecom logo. Where the logos can only be reproduced in a single colour, the box colours are distinguished from the ground colour by vertical and horizontal hatching. ‘What’s typically PTT is that you have a lot of colour and little type,’ says van Bragt. As with post offices the world over, colour is a distinguishing feature, a legacy of the days when letter boxes were recognised by the colour they were painted.

This much of the Dumbar identity is non-negotiable. But from here on freedom is granted in increasing doses by means of a four-tiered system devised by Dawn Barratt, an American working at Studio Dumbar. And it is the play between the rigidity of the logo itself and the flexibility possible in other PTT design work that ensures the very being of the PTT pervades Dutch life. Its buildings, many of them conveniently constructed with a ready-made grid of glass curtain-walling, support variations on the design. PTT trains have logos of different sizes stamped across them at wild angles. PTT uniforms are less institutional; company sportswear is even sold to all-comers. And then, of course, there are the coffee-cups that are tempting a new breed of designer kleptomaniac.

PTT is proof that a large and ambitious company with eyes on European expansion need to shun its local heritage. And it is a reminder that apart from its money, the image of the country’s post and telephone company is the most powerful expression of its design.

First published in Eye no. 1 vol. 1, 1990

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.