Winter 2008

Foot Prints

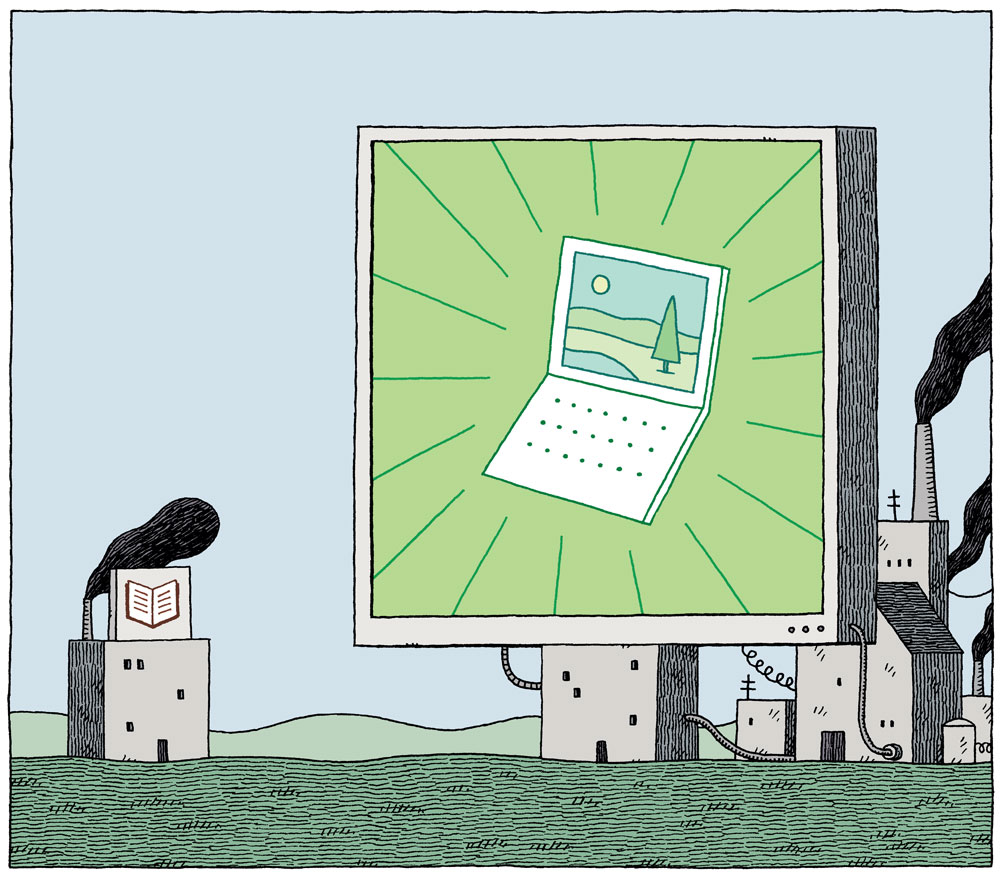

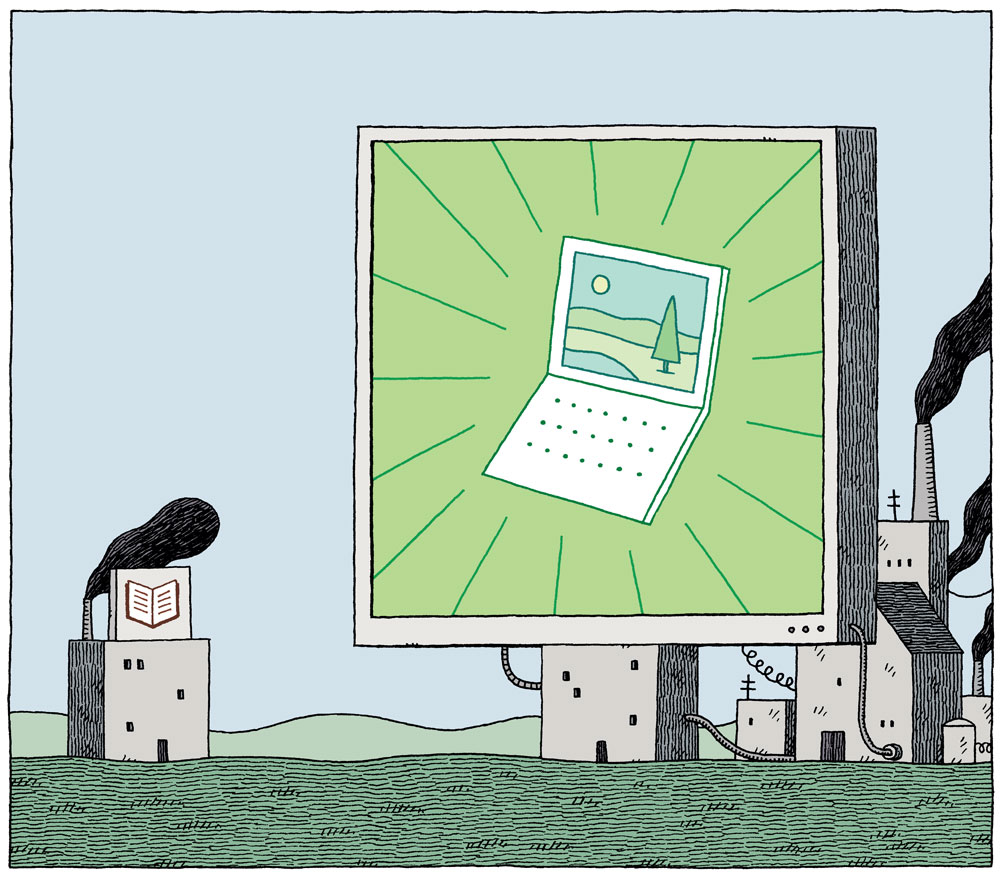

Why do we assume that online publishing is greener than print and paper?

When it comes to the environmental impact of communication media, print is usually singled out as the dirty old man. It is understandable why that should be. In the shiny, weightless online world, everything happens in the twinkling of an eye and it is possible to instantly view a Web page or email created on the other side of the world. With the rise of the iPhone, Wifi and 3G dongles, this viewing can be anywhere, as long as you have battery life and a few bars of signal.

The technology is easy to use – and makes it easy to forget that there is a huge infrastructure humming away behind the scenes. Factories have to produce the laptops, smartphones and flat panel displays that are the windows to this electronic world; and communications networks and data centres need to be powered 24 / 7 to allow us the convenience of access any time, any place, anywhere. Jonathan Koomey of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California has calculated that the data centres that drive the internet already consume one per cent of global electricity capacity, and that their consumption is growing at seventeen per cent per year (New Scientist, 4 October 2008).

By contrast, the physicality of the printed page shows rather than hides the resources that went into providing the paper that supports the design. Every time we turn the page of a magazine or pick up a book, it reminds us of the raw materials and energy that have gone into its production.

Earlier this year, Sainsbury’s, the UK supermarket chain, announced its decision to distribute its report and accounts in electronic form only, claiming environmental reasons. Michael Johnson, president of the British Print Industries Federation (BPIF), decried the move as a ‘phoney’ attempt to cover up a cost-cutting exercise. Johnson said: ‘The paper industry is one of the great success stories of modern recycling. Paper is not the enemy of the environment it is made out to be.’ Sainsbury’s, however, defended its decision as being ‘in keeping with our corporate responsibility principle of “respect for our environment”.’

The information gap

However neither side produced any data to back up their claims. This spat highlights the lack of accurate information about the environmental impacts of different media. Johnson was correct to say that paper is a sustainable product that can be recycled, but there are complications. Recycling is only one aspect of sustainability. Depending on the type of paper, and the methods used in the paper-making process, a recycled grade may actually have a larger carbon footprint than one produced from virgin fibre. Unlike newspapers and paperback books, which use mechanical papers, annual reports and accounts generally use wood-free fine papers, which can be a net producer of energy. These are free of lignin, which bonds cellulose fibres together in trees, and causes the yellowing in mechanical papers. Once removed, the lignin is burnt to generate steam and electricity, which releases more energy than the paper’s manufacture alone requires, and this surplus electricity can be sold back to the grid! This example shows that environmental questions are complex, and rarely boil down to one simple answer in any given issue.

At the moment it is hard for either side to do a like-for-like comparison. Suppose a study of environmental footprint were to contrast the cradle-to-grave impact of printing and distributing a copy of the report to 120,000 shareholders with the manufacturing and energy outlay needed to make it available for viewing online, to those who choose to view it. Producing such a study would be extremely complicated.

The process of working out carbon footprints, something in which the UK is a world leader, may soon become simpler with the introduction of the British Standards Institute’s (BSI) Publicly Available Specification 2050 (pas 2050) guidance, for calculating the ‘life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of goods and services’. The BPIF has pledged that the print industry will follow this.

There are many other initiatives which will make it easier to evaluate the environmental back stories of our reading habits. Last year, a study for KTH, the Swedish Royal Institute of Technology, compared the environmental impacts of reading the Swedish newspaper Sundsvalls Tidning in printed form, on a PC and on the iLiad e-reader (Screening Environmental Life Cycle Assessment of Printed, Web Based and Tablet E-Paper Newspaper, by Asa Moberg et al, Stockholm: KTH). This considered the entire lifecycle, from editorial production, through distribution and reading, to the end-of-life disposal of the paper or the two electronic devices. In addition to the current hot topic of global warming, it also considered such environmental factors as acidification, eutrophication (nutrient build-up caused by fertiliser run-off), ozone depletion, photo-oxidant formation and resource use, as well as toxicological impacts.

For each method of reading the paper, different potential environmental impacts came to the fore. For the printed version, paper production was the significant activity; for the Web, it was online reading; and for the e-reader, production of the hand-held device. For a 30-minute reading-time, in Sweden it was the printed paper that had the largest carbon dioxide emissions, but in a pan-European scenario, the Web-based version was the worst, a difference attributed to differing ways of generating electricity. Other issues that might affect environmental impact included the number of readers per copy of the printed and e-tablet papers, the lifetime of electronic devices, and the multi-use of electronic devices.

The report made it clear that more data was still needed on the production of the e-tablet, the e-infrastructure for the delivery of Web pages and the recycling of electronic waste.

Though it is difficult to draw conclusions, it is obvious that the relentless evolution in consumer electronics increases the problem of electronic waste. In this case, smartphones such as the iPhone could show the way towards a single device replacing many.

Legibility and the environment

Reading time may not be the most obvious factor when choosing what media to use, but the suggestion is that the longer you spend looking at something, the greater the advantages of paper and print. And if the time taken to view something affects its environmental impact – and viewing time is directly dependent on legibility – then editorial design and typography will have a central role in improving the green credentials of electronic media.

Environmental considerations alone will not kill print or online communication, but a better understanding of each medium’s sustainability strengths and weaknesses can help to make better-balanced decisions about which to use and how. It may be that environmental, ergonomic and physiological factors all move in the same direction, so that the more time you are going to spend reading and the more complex the information, the better it is to read from paper – from the point of view of your planet, your eyesight and your reading pleasure.

For readers who do not want to be harried and distracted by online chatter, perhaps we may yet see a Slow Information movement akin to the Slow Food movement; both are better for the digestion, and better for the world.

Top: Illustration by Tom Gauld / Heart.

Barney Cox, executive editor, Haymarket Print Group, London

First published in Eye no. 70 vol. 18, 2008

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue.