Autumn 2008

Hunger for the visual

Moscow Photobiennale curator Olga Sviblova is re-acquainting Russians with their visual history

Moscow’s Café des Artistes was a favourite hangout for Alexander Rodchenko and Vladimir Tatlin at the height of their Constructivist brilliance. Almost a century later, this Art Nouveau delight is a regular haunt of Olga Sviblova, founder / director and curator of the International Moscow Photobiennale. The Café was one of more than 40 locations for this year’s event, from 21 March–30 May 2008.

Inspired by meeting Henri Cartier-Bresson at the original Café des Artistes, in Paris, in 1995, Sviblova launched the Photobiennale the following year. A tirelessly obsessive curator, she edits the collections amassed in the Moscow House of Photography, which she founded – also in 1996 – to chart the story of Russian photography. It houses more than 80,000 images.

Over the past decade, Sviblova has helped re-introduce Russians to their photographic history through newly discovered works that she presents alongside young contemporaries and legends from abroad. ‘Lenin saw photography as a strong visual weapon for a highly illiterate population, a propaganda weapon,’ she says. Stalin, though, saw its subversive powers, and cameras disappeared, except in the hands of state documenters and surveillance departments. In 1928 he installed the committee running his Five-Year Plan inside the elegantly arcaded GUM department store, another of the Photobiennale’s venues. With the committee went his Ogoniok magazine, which carried bright, optimistic colour photographs into every corner of the empire. ‘People only saw mises en scène of happy people,’ says Sviblova with disdain. ‘There are no faces [in the archives] that aren’t smiling.’

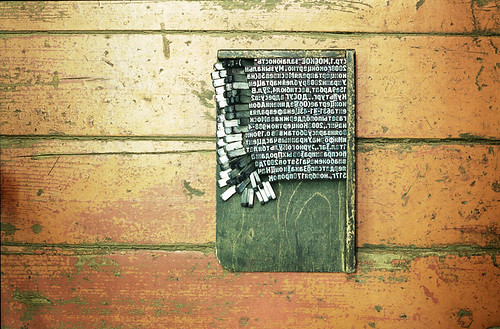

Still life from Natalia Pavlovskaya’s documentary of one of Moscow’s last remaining traditional print works.

Top: Sergei Chilikov’s ‘Two Holidays’, 2007.

Ogoniok has a significant role in Russian photographic history. The magazine’s ‘Best’ series – best rug-maker, engineer, grape-picker, etc. – shows rosy-cheeked farm-workers and young women in overalls tending machinery. ‘Heroes of the Fifth Five-Year Plan’, Sviblova’s selection of Ogoniok images, features large, modern prints in gorgeous, muted but saturated 1950s colour. Robert Diament and Dmitri Baltermants were favoured photographers, the Soviet equivalents of Life magazine staffers. The former’s portraits of workers in factories contrast with his soft-toned records of Khrushchev relaxing. Baltermants’ eye for design and pattern was applied to aerial shots of trams in snow, umbrellas and landscapes, but he was also invited to shoot an official portrait of Stalin in his coffin, immersed in flowers.

One focus of the 2008 Photobiennale is a hugely ambitious, chronological stroll through 150 years of Russian photography, under the title ‘Primavera’ (variously translated as ‘Spring’ or ‘Primrose’). A beautiful and educational experience, it moves through history, from black and white to colour, and, in Sviblova’s words, ‘from the tsarist era through collectivism, militarism and austerity, from daguerreotypes painted with oil to Polaroids and Photoshop’.

This recasting of history through photographs never seen in the lifetimes of most visitors makes a powerful effect, and is threaded with the different approaches of the Pictorialists, Constructivists and Soviets. Rodchenko is represented by Rumba, a still of couples dancing from his 1928 film Albidum, hand-coloured with crayons to simulate a colour negative. Among the classics, it is pleasing to see occasional deviators, and Vasily Schepkin’s Herd is a marvellously composed, quietly minimalist design created just from a line of cows climbing a long slope against a river valley.

Elsewhere, hand-coloured postcard-like landscapes, painted bromoil prints, salted paper chosen to enrich the colours of peasants’ costumes, washed-out panoramics of Moscow, moody collotypes of the Crimean resort of Yalta, and sensuous prints of snowy 1930s farmyards make up a memorable collection. Framing the ‘Primavera’ collection are French legends who had a bearing on the Russian style: Edouard Boubat’s handling of light and shade in his pensive mid-twentieth-century portraits of André Gide; Mario Giacomelli’s prints, treated to resemble drawings.

But for Sviblova, Bogdan Konopka is ‘the hero of the festival’. His small, dramatic De Natura Rerum bucked the trend for ever-greater ‘canvases’ and included brooding, abstract colour portraits requiring long exposures to perfect the magical effect, ‘making light beams tangible’, as she says.

One of her re-discoveries is the experimental chemist / photographer S. Prokudin-Gorski, who worked with the Lumière brothers and made ‘thousands of autochromes’. Here she exhibits his delicate parade of fashion, travel, ethnographic reports, made using a ‘three-coloured’ technique involving colour filters. It is accompanied, logically, by a rare sighting of an informal collection from the Lumière family album.

Valery Nistratov captures the innocence and awkwardness of Girls at the Disco, 2000.

Contrasting with the unreal reality of Ogoniok’s archives, Yevgeni Shcheglov’s marvellous and brave ‘View from the Car’ series provides black and white scenes of Moscow’s sparsely populated streets in the 1950s. Composed and framed like 1920s and 30s film stills, they were shot in secret at the height of KGB surveillance and possess a le Carré-esque tension. Half a century later, the secretive Boris Saveliev continues to haunt those streets, bringing an eye for angularity and illumination reminiscent of Man Ray.

The profusion of documentary work by young Russians in the Photobiennale is a logical direction for a country deprived, for decades, of honest reportage. Two dedicated photographers who focused on leisure-time among the new working class shifted to Western monochrome to gain maximum expression. Andrei Gordasevich’s ‘Tutaev’ is a lyrical yet unromantic photo-essay set in a rural village during a festival: old cars, wooden houses and sparse woods form backdrops for families picnicking among the woodpiles, but there is also a startling portrait of two children by a lake, evoking Vanessa Winship’s Turkish Sisters. Sergei Chilikov’s ‘Two Holidays’ explores similar territory, and is also devoted to details such as piles of plucked chickens and sawn tree trunks. His essay on young, suburban working-class weekenders takes a soft-focus colour approach to the drinkers’ chaos.

The significance of cinema in Russia is a constant presence in the photography. Valery Nistratov’s Girls at the Disco is outstanding: he appears to choreograph the isolated groups of girls dancing together along a horizon of bare grass under a naked street light, creating an image as Modernist and intriguing as any Gregory Crewdson street scene. Equally refreshing is Ludmila Zinchenko’s ‘Unobjective Moscow’, taken with a pin-hole camera. Lyrical and impressionistic, it was produced by quietly spying through windows and doors, then printing onto canvas to exaggerate the images’ magical, grainy moods. The compositions seem cinematographic, but Sviblova declares: ‘She thinks like a painter.’

The paintbrush of the former supermodel Yulia Milner is digital, her startling Universe video installation represents ‘the eroticisation of space’ – richly coloured abstracts of floating galaxies and nebulae that are beautifully composed from digital close-ups of her own genitalia.

Herd, Vasily Schepkin’s 1960s gelatin print.

The influence of the Magnum style on young Russians has grown over the past decade, alongside that of the internet and international exhibitions in Moscow. In the former eighteenth-century wine factory that is the Winzavod Contemporary Art Centre, five Magnum photographers, under the title ‘Light and Shadow’, are a constant draw. Narrative is part of the appeal, and Lise Sarfati’s studies of fashionably ordinary teenagers in ordinary settings are also popular. Magnum’s only Russian member, Gueorgui Pinkhassov, draws eager crowds to his Just Like Light from a 1970s essay set on Moscow’s streets, all shadows and icy lighting, which suited the era. Alex Webb’s ‘Colour: The Suffering of Light’ is intense, unusually abstract, and worked with shadows, unlike Pinkhassov’s explosions of light. In similar vein, beyond the Magnum club, Alexander Smirnov’s ‘Colour and Shade’ project is based on visits to his old St Petersburg neighbourhood. He harnesses ambient light and Rodchenko-like beams into a marvellous geometry that captures the mood of nostalgia and loss. And Vladimir Mishukov’s very contemporary Premonition – a girl sleeping on a bed in a sparse room flooded by light – is a filmic set-up, marking the growing interest in bleak landscapes and perspectives and minimal design.

Honest portraiture has made a comeback after decades of politically controlled image-making. Natalia Nosova’s poignant ‘Imprints’ shows large-format, black and white close-ups of faces, printed in that high-contrast technique associated with post-Avedon Londoners such as Nigel Parry and Steve Pyke. Nosova closes in on the faces and hands of survivors, allowing the imprints of their life stories on gnarled fingers and lined faces to tell their tales.

‘To know your future, you must know your past,’ declares Sviblova during one of her introductions. I found this rich collection of work exhilarating and packed with surprises, but its real significance is for Russian audiences, particularly those young artists emerging from what Sviblova calls ‘a visually hungry generation’.

Sue Steward, writer, curator, St Leonards, Sussex

First published in Eye no. 69 vol. 18

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.