Summer 2016

I am a poster

anonymous designers

A. M. Cassandre

Dread Scott

Werner Kranwetvogel

John Thomson

Ernest C. Withers

Valentina Calà

Mickael Menard

David Crowley, curator of ‘The Poster Remediated’ at the Warsaw International Poster Biennale, examines some of the relationships that exist between posters and the human body

Posters have been a largely static medium for most of their history. Pasted up on walls or installed in advertising units, they attempt to arrest the attention of passers-by. Famously, A. M. Cassandre, the great Art Deco designer, is reported to have designed his three-frame ‘Dubo Dubon Dubonnet’ poster – featuring a partly coloured-in outline of a bowler-hatted man being filled by the aperitif – to be viewed from a fast-moving automobile.

Sometimes, however, the poster comes to the viewer. In fact, mobile posters can be traced back to the earliest years of the medium. ‘Boardmen’ in London in the nineteenth century eked out a meagre existence by walking through the streets of the city carrying commercial messages on their chests and backs.

Suffragettes before the First World War became boardwomen by donning large letterpress posters demanding the vote. Protesting against their exclusion from public life, they took their messages to settings that were the domain of men.

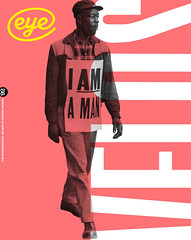

Mobile posters acquire heightened meaning from the settings in which they appear, even if only temporarily. In 1968 African-American sanitation workers on strike in Memphis, Tennessee, carried posters with the slogan ‘I am a Man’ to the site of power, City Hall. Printed in the basement of the protestors’ headquarters, the Clayborn Temple, ‘I am a Man’ became the best known civil rights poster of the era by being recorded by press photographers. Dozens of screen-printed posters became millions of forceful images when they appeared on newspapers’ front pages – another kind of portable poster.

‘A London Boardman’ photographed by John Thomson from Street Life in London (1876-77).

Top: Werner Kranwetvogel, Backdrop #10, photographic print, 2009. Photographing the Arirang festival in North Korea, German film-maker Kranwetvogel recorded the faces of participants who are usually entirely obscured behind propaganda images. Kranwetvogel’s photographs provide a rare glimpse behind the official mask.

Mobile posters often attempt to tap pathos for political effects. Carried on the body, they turn gestures – a clenched fist or a sombre face – into an articulate statement. The feminist activists Femen go further, creating what they call ‘body posters’ through which ‘truth [is] delivered by the body by means of nudity and meanings inscribed on it’. Objecting to domestic violence, prostitution, pornography and many forms of misogyny, Femen activists write slogans across their breasts and engage in semi-naked acts of civil disobedience, often targeting politicians and religious leaders. The ‘correct’ gesture or body stance is vital: Femen train novices how to stand when protesting – feet apart and firmly rooted; unsmiling; and with an aggressive demeanour.

Femen’s ‘body posters’ – like the ubiquitous ‘Je suis Charlie’ posters seen in the aftermath of the attack on Charlie Hebdo on 7 January 2015 – are essentially individual gestures, even if their effects are amplified by collective action; they operate at a human scale, literally.

Other human posters aspire to be monuments. In North Korea the Arirang Games, a mass gymnastic spectacle, has featured enormous ‘living’ posters: thousands of performers – mostly children and young people – sitting in the stands of the festival stadium hold books of coloured pages above their heads, turning the pages according to a strict, carefully programmed choreography. Viewed from a distance, propaganda images of the ‘good life’ in the last surviving Stalinist state in the world ripple into life.

Rally in Brussels expressing solidarity with the victims of the attack on the offices of Charlie Hebdo in Paris on 7 January 2015. Photograph: Valentina Calà.

David Crowley, head of Critical Writing in Art & Design programme at the Royal College of Art, London

First published in Eye no. 92 vol. 23, 2016

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. You can see what Eye 92 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.