Winter 2010

Icons for the people

A new V&A display and a book trace the method of visualising data pioneered by Otto Neurath in the 1920s

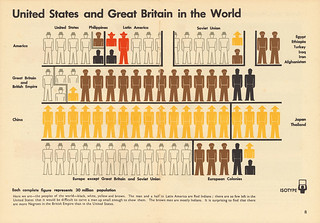

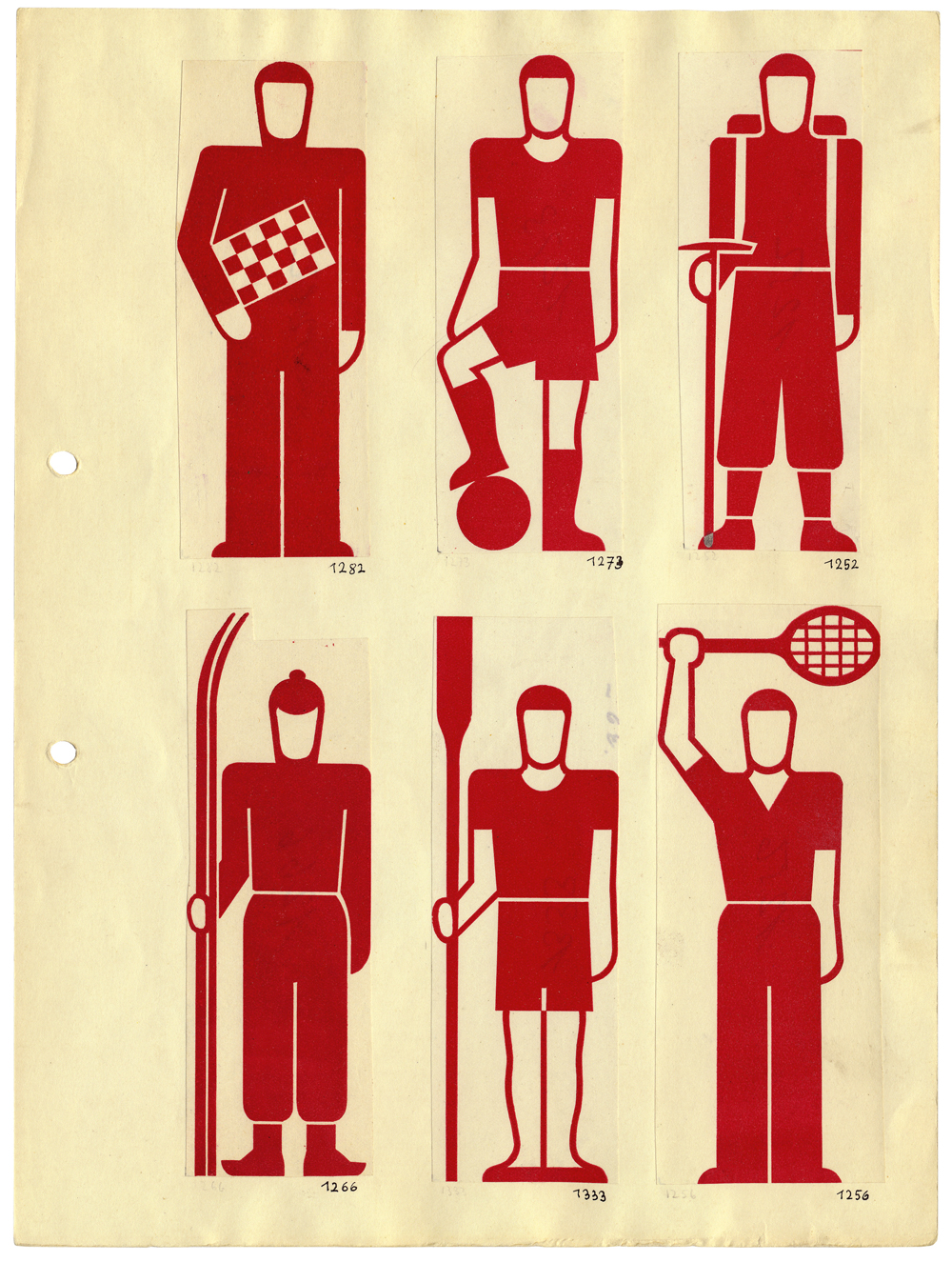

The pictograms we see around us, for public signs, at sports venues, on our computers, phones and tablets, all bear some trace of those first designed in the 1920s for Isotype (International System of Typographic Picture Education), a pioneering method of visual communication.

Pictograms were crucial to Isotype, picturing things that could then be quantified and compared. They also gave Isotype a language-like consistency that served the organisation’s broader, educational aims.

Those involved in Isotype – its founding figure, Otto Neurath; Marie Reidemeister (later Neurath); and Gerd Arntz – applied themselves to a wide variety of projects. Their varied visual solutions testify to Isotype’s versatility in showing social and economic relations and facts about health, history, technology and science.

Isotype’s graphic language, now so recognisable, was also powerful and refined. But achieving all this was neither quick nor easy, and needed working out through trial and error. For Otto Neurath, Isotype could not be wholly theorised, only increasingly better articulated through work and experience.

A selection of this work can be seen in ‘Isotype: International Picture Language’ at London’s Victoria & Albert Museum this winter. Beginning in 1920s Vienna, the display spans more than four decades of Isotype activity in Austria, Britain, the Netherlands, the Soviet Union, the United States and points further afield. It samples Isotype’s many uses: for visual education in inter-war Vienna, pictorial statistics in Moscow, health campaigns in North America and ‘soft’ propaganda in wartime Britain.

Isotype explanations of postwar planning, reconstruction and welfare are shown, as are educational books for children, and public information campaigns in 1950s West Africa. Artists’ prints and historical graphic matter indicate the wider influences shaping Isotype from the start.

The exhibition is also an opportunity to encounter the particularity of Isotype. Original large charts from the 1930s are surprisingly three-dimensional in construction, and re-animate the disembodied flatness typical of Isotype reproductions.

Books, posters, portfolios and pamphlets offer evidence of how, and in what form, work was first made, distributed and used. Working materials for print and moving image show the rougher edges of design and production.

Apart from its continued relevance to the design of information, Isotype offers a fascinating case history of the Modern movement, one whose trajectory through time and under different national and cultural influences gave rise to work that was pragmatic, utopian and, above all, international. The current V&A exhibition revisits Isotype’s impressive range of interests, concerns and applications to consider afresh its scope and importance.

Neurath’s visual autobiography

Isotype founder Otto Neurath wrote his visual biography in the two years before his sudden death in 1945 but the manuscript has remained unpublished until this year. From Hieroglyphics to Isotype: A Visual Autobiography (just published by Hyphen Press) assembles the book from several edited drafts and provides many engaging insights into the origins of Isotype. Neurath’s intention was to show ‘the different sources from which Isotype has evolved’, and the five chapters are peppered with childhood recollections that are warm but rarely sentimental or self-indulgent.

The newly published edition, edited by Matthew Eve and Christopher Burke, is illustrated by historical examples that span several centuries and styles: cave paintings; Mayan reliefs; Descartes’s Opera philosophica (1685); Berghaus’s Physikalischer Atlas (1845); the Illustrated London News; and diagrams and maps of military campaigns and battles.

Returning to the books he recalls from his father’s extensive library, Neurath invites us to look through the eyes of a child, recollecting the ‘shinies’ (Victorian stickers) of the scrapbook he kept as a four-year-old, and the unfettered access he had to his parents’ books: ‘while still a small child, I came into direct contact with books that later on became important to me […] It would surely be possible to give other children the advantage that I had by providing books for nursery schools and other libraries for the young that are not merely children’s books but are of a kind that will accompany them as they grow up.’

When it comes to instructional illustrations and diagrams, Neurath has no time for ‘pretentious draughtsmen’ who dress up their images with what he dismisses as ‘Rembrandtesque tricks’: ‘Thus I started regarding draughtsmen of educational pictures more and more as servants of the public and not as its masters. ‘Tell me your story and spare me your stammering and stuttering,’ I would have said. ‘Be simply a friend to me and do not drape yourself up like a bad actor in some travelling company.’

In his fifth and final chapter, which recounts his experiences with Isotype, Neurath discusses the ways in which different modes of information are experienced: books, for which a ‘reader has more time at his disposal and can look at a visual argument again, without much difficulty’; exhibitions, in which visitors ‘can stand around an exhibit and discuss it freely’; and films, in which the pacing of information is controlled by the producer.

‘This acknowledgement of the peculiarities of different fields of visualisation is of great importance,’ he writes. ‘One should avoid ranking them all together and giving relatively high or low marks to each. They all have different qualities that cannot be combined into a whole and given a single index number.’

Neurath continues: ‘Isotype leads to the presentation of events stripped of superfluous details by means of an international language-like technique. Training people to deal with the mass of material in a documentary photograph also leads them to the international visual environment of modern man.’

At the end of this chapter, Neurath returns to his earliest impressions, citing Samuel Smiles’s book Self-help as an important influence, quoting his observation that people ‘learn through the eye, rather than the ear; and whatever is seen in fact, makes a far deeper impression than anything that is read or heard […] especially […] in early youth’.

‘What I owe to my eyes,’ he concludes, ‘perhaps other people also owe to theirs, and they will tell their story. I think there must be many people […] who want to be as all-round as possible and to have an opportunity of getting information on all kinds of different subjects, so that they may at least grasp the main points without being overwhelmed either by unarranged details or by the intellectual flood of explanations and applications that so often smothers us ‘men in the street’. Even people who are skilled in one field may feel rather helpless in others – and that is you and me, we ordinary folk who do not aspire to be members of an ‘elite’ to which so many people claim to belong. Where all-round humanity is involved (not specialised knowledge) there are no experts. […]

‘There is no field where some humanisation of knowledge through the eye would not be possible. This is the goal of Isotype – to communicate knowledge as far as possible, reducing the gulfs between nations and language groups.’

First published in Eye no. 78 vol. 20.