Spring 2005

Looking for clues

Notebook in hand, Paul Davis works like a journalist, trying to figure out what makes us tick

I have to admit I got it wrong with Paul Davis. My aim was to write an essay about British designers’ favourite artist / illustrator, rather than a profile, but I decided to go and see him anyway to pick up information about his way of working. I planned to maintain a polite, professional distance, but Davis is friendly and sociable, with a way of pulling you into his world. He enjoys food, drinking, telling stories, hanging out. And he wanted to go for lunch, so we did. Davis spoke freely, with great warmth, and I concluded this first meeting with the sense that he would probably make an exceptionally communicative interviewee. Perhaps an interview-based profile was the best way of tackling this, after all. Still, I wanted to write something more discursive.

We made another date to meet. This time he was edgy. The prospect of a more formal, tape-recorded interview seemed to rattle him. My main concern was finding somewhere quiet enough to make a good recording, and we wound up in a dark brown, dimly lit ante-room, like something out of a David Lynch film, in a bar near to his studio in Curtain Road, East London. With the tape running, Davis was an odd mixture of volubility and slightly awkward reticence. It was hard to glean much detail about his intentions as an artist – he would say two or three short sentences and then clam up. But in other more private and emotional matters, which I hadn’t asked about, he was almost too forthcoming, though I couldn’t help admiring his openness and generosity of spirit.

I emerged not much the wiser about his methods, but with my impressions of his work, as I had first perceived it, deflected, if not compromised, by my growing awareness of the man. I had lost my detachment. After such generosity, how could I be anything other than generous in return? I had even heard his view of critics – ‘a really horrible way of living’. This didn’t appear to be personal, but being treated as an exception only made it worse.

‘I DON’T GIVE A DAMN ABOUT FAME AND ALL THAT SHIT.’

Davis was born in Paulton, Somerset in 1962. He graduated from Exeter College of Art and Design in 1985, but it was more than a decade before he made much headway. In the late 1980s, he worked mainly in collage, then the dominant approach in illustration. The high point came in 1988 when he exhibited a series of personal pieces created with David O’Higgins in a show titled ‘Spanking Britain’. The 25 collages, Davis explained at the time, reflected disillusionment with design, the media, popular culture, fashion, the financial sector, postmodern housing in Docklands, and the invention of the yuppie. He subsequently abandoned collage, realising that he would much sooner draw, but found himself churning out undemanding magazine illustrations to order. The sense of disenchantment remained.

In 1996, it occurred to Davis that constant seasonal change meant that there might be a future in fashion illustration and he showed a collection of images to Jo Dale at The Independent on Sunday’s Sunday Review. Dale commissioned a series of full-page watercolours illustrating clothes and accessories by Gucci, Chanel, Calvin Klein and Paul Smith. Some of Davis’s later traits were already evident: random scribbles, figures floating against nebulous backgrounds, and a kind of studied clumsiness, as though the artist were drawing less well than he could. Within days, Harvey Nichols had approached Davis to create an eleven-window display to promote the menswear department at its Knightsbridge store, while Sir Terence Conran, also thinking big, commissioned an 80 ft mural for his new Bluebird restaurant in Kensington. By the end of the 1990s, Davis was collaborating with British advertising art director Tony Arefin in New York on IBM’s Magic Box campaign, his biggest, most lucrative project to date.

He continues to work for some high-profile commercial clients – ads for Virgin Atlantic, an annual review for Channel Four – but these illustration projects display a softer, more pliable, more decorative side. Davis understands design, appears to get on well with designers and is sympathetic to their aims, but like many who straddle the art / design divide, it is clear that the work that matters to him most allows him to record his experiences and reactions without compromise. These more personal pieces have won him attention. The commercial projects trade off the Davis charisma with some charm, but if they were the sum total of his output we would not be talking about him.

‘I’M JUST A NOSY BASTARD.’

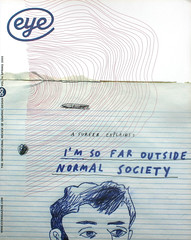

Davis seems most himself when, on the page, he is doing very little. A drawing of a surfer, from a series of ten, is as spare and mysterious as a haiku. Davis captures the essential features of the man’s face with just a few shaky outlines and scribbles. His eyes seem unfocused: he is lost in world of his own. The stubble on his chin suggests his casual lifestyle and the sideburn proclaims ‘dude’. ‘I’m so far outside normal society’, says the hand-lettered copyline over his head. Above that, Davis has written ‘A surfer explains:’ and this small addition is vital. We would have no idea without it who the man is, but it also establishes a context for his disaffection. He evidently sees himself as part of a special group, living by an alternative code. His remark implies that ‘normal society’ could never understand him, yet he looks spaced out, wasted, not entirely there. There is an unmistakable note of irony in Davis’s scene-setting. The man is clearly kidding himself. He isn’t the bold, socially radical surf hero he imagines himself to be.

One final element of the image is also typical of Davis’s work. The drawing has been made on a narrow-ruled notepad, with a torn top edge and crossed-out elements left as they stand. The picture may or may not have been created in situ (on a beach? in a bar?) but the notepaper adds a feeling of immediacy, informality and verisimilitude. Davis might, of course, have made up this surfer character, but the sketch has the air of something seen and heard and faithfully transcribed, like a visual report.

This is how he operates. The people in his pictures seem real because usually they are real. He interrogates friends and acquaintances. He listens in on conversations in bars and restaurants – ‘Yes, my husband’s penis is rather small’ – and overhears moments of unfortunate candour and self-revelation in the street: ‘Fuck off. Of course I love you.’ He approaches strangers in hotel lobbies, asks them impertinent questions and makes a careful note of what they say. His likeable manner sets his subjects at ease and they allow him to get in close. In some ways, Davis works like a journalist with notebook in hand, looking for clues to what people are thinking about now and what makes them tick. His drawings may be reduced to a few simple elements, offering the viewer a deceptively quick hit, but he has an unerring ability to delineate – and flay – a personality with just a few incisive strokes. He can do this with graphite, coloured pencil, ink or paint. These faces are both characters and types. We feel we know people like this.

‘I’M MISANTHROPIC. I CAN’T HELP IT.’

The bleakness of Davis’s view is alleviated by humour, but its prevailing colour is black. His characters are empty vessels: foolish, ignorant, self-centred, deluded and boring. Davis returns repeatedly to sex and relationships (with the emphasis on sex), to the self-aggrandising folly of the business world, and to the general emptiness of it all – in one drawing even bullshit comes in a Liquitex tube. ‘I think new media is fascinating’, observes a talking potato head, a minimal figure even by Davis’s usual standards. God Knows, his latest publication from Browns, introduces us to a grinning Director of Global Sloganeering and an equally shifty Product Revamp Director – their ponderous job titles are comment enough. In Blame Everyone Else (2003), also for Browns, Davis scratches out the golden tresses of yet another jargon-spouting new media lackey: ‘D’you realise that cross-platform sharing has been a reality for some time now, as has multi-tasking, living brands, resonant messaging and many more’? she inquires, her empty words occupying far more space than her own image. Another small, bowed figure appears to be afflicted by almost every malaise that modern life can throw at a person: ‘Bankrupt, overdrawn, credit blacklisted, lonely and terminally ill.’

Davis has been described as a satirist, but he dislikes the term. Nor does he regard himself as a moralist, though he admires William Hogarth, who certainly was. He takes issue with the suggestion that his work criticises the world, even though this is what it does. Davis prefers to describe his output as a ‘reflection’ of what he sees, and himself as a ‘misanthropist’. When I pointed out that the definition of misanthropy – a little-used word these days – was hatred of the human race, he denied that it meant this. As a self-declared ‘beauty-ist’ and life-loving romantic, he seems to interpret misanthropy as the stance of someone struggling with deep dismay at the way people so often fall short of their potential to live good lives, behave decently and tell the truth.

Here I run into problems because, while I can accept this statement of intention after becoming acquainted with the man, it certainly wasn’t quite how I read the work before I met him. Davis’s drawings are unsentimental and unsparing, often to the point of cruelty. His most sustained feat of reporting and concentrated jet of bile is the book Us & Them (Laurence King, 2004), documenting what the British think of the Americans and the Americans think of the Brits. Davis’s caustic ear for self-serving nonsense and fatuous opinions delivered in tones of great authority is pitch perfect and the acid flows from his pen. ‘There’s a certain “old school” arrogance. AH HATE IT!’ shrieks a woman he encounters in a Chicago hotel. From the way Davis draws her, with desiccated body, face screwed tight in fury and ropes of hair hanging down to the floor, it is hard to believe that the loathing isn’t mutual. In many ways, the ostensible theme of the book, transatlantic misperceptions, seems like no more than a pretext. Us & Them’s real subject – and it is Davis’s abiding concern – is the fallibility and delusion that is part of our human nature, wherever we happen to live.

‘I CAN’T HELP MAKING PICTURES. IT’S ALMOST NOT MY FAULT.’

A number of striking image-makers have come to the fore in recent few years, but Davis is top of the heap. He was voted ‘best illustrator working today’ by readers of Creative Review in 2002. Why do people like his work so much? It has an attitude, a spark of ruthlessness, that most colleagues lack and, in some crucial respects, it is totally in tune with the times. The maladjusted weirdness of ordinary people has become a staple of alternative British television comedy. Programmes such as The League of Gentlemen, Chris Morris’s Jam, Little Britain and Green Wing parade a gallery of dysfunctional characters: self-fixated but lacking in self-awareness, emotionally incontinent but unable to make a real connection, sociopathic to the point of depravity. Oddball tv reporter Louis Theroux and outrageous chat show host Graham Norton encourage members of the public to expose themselves for our entertainment. No foible, obsession, bodily function, act of unpleasantness or sexual mishap is so private, embarrassing or shameful that it can’t be mined for a laugh.

But what, we might ask, is the underlying purpose of the joke? Is it the satisfaction of seeing social taboos broken? A therapeutic moment of recognition that something true but previously unstated has been revealed, allowing us to go forward as better adjusted human beings? Or a darker, less wholesome kind of pleasure in prurience and humiliation for their own sakes? Whatever his intentions, many of Davis’s drawings exhibit much the same fascination with areas of experience that were once off-limits to popular culture.

He is at his most ambivalent when he deals with sex. The primeval, clay-like men and women displaying their genitals in Lovely (Colette, 2003) look deeply uneasy, with their eyes popping out of their heads. The volume numbers written on the pictures and the printed grids used as backgrounds add to the perception that they are specimens for study. Davis might be showing us how these people have chosen to objectify and demean themselves by assuming porn poses, or he might just be saying: look, this is how we humans are, isn’t it ridiculous and, let’s be honest, rather funny? Then again, it is possible that Davis really doesn’t know quite what he means by some of these sexual images. When I asked him about it in the gloom of the David Lynch bar, the only answer he came up with, delivered as though nothing more needed saying, was ‘I love sex.’

‘I HAVE NEVER FOUND MY VOICE. THAT’S THE BEAUTY OF IT. YOU NEVER DO.’

Meeting Davis certainly complicated my sense of his work. I had him pegged as exactly the kind of person that he says he is: a misanthropist. Now he strikes me as more like a disappointed idealist. It is socially unwise to make moral rulings about other people’s behaviour today – what gives us the right? Often, though, as in the surfer portrait, there can be little doubt about what Davis thinks of his subjects. He dares to make a judgement. David Carson, famous as a surfer, commissioned the surfer pictures for Big magazine in 2001, but rejected them all as too negative, according to Davis. Clearly the drawings had made their point a little too effectively.

At other times, a Davis image could be saying almost anything. What does his ‘modernist vagina building’ inscribed on MetaDesign’s letterhead mean? Or the two soft toys hanging by their ears from a washing line? He would probably relish this ambiguity, since he likes the idea of a critical response that circles endlessly around the subject, opening up further lines of inquiry, without reaching a firm conclusion. But this is the dominant approach in most criticism today (as distinct from evaluative reviewing) and it could be seen as a failure of nerve, a sign of moral exhaustion that cannot be reconciled with a worldview as passionately committed as Davis’s. ‘Being a romantic,’ he says, ‘you are bound to be let down.’ His drawings propose one thing with indelible conviction. It’s not just everyone else who is to blame. It’s all of us.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, London

First published in Eye no. 55 vol. 14 2005

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.