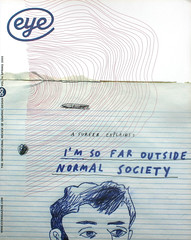

Spring 2005

Lost worlds

Vernacular photography. Innocence regained? Or just another kind of fiction?

At the end of 2004, the ‘Trachtenberg Family Slide Show Players’, a group of Seattle-based musician / collectors gave a show at the Soho Theatre in London based on their extensive collections of slides from the 1950s, 60s and 70s. The Slide Show Players, Jason, Tina and Rachel Trachtenberg, have built narratives, in music and lyrics, that take collections of vintage transparencies away from the niche to which they have been consigned – an interesting, quaint but essentially indecipherable oddity – and made them into fast-moving, often highly comic parables of postwar America. The Trachtenbergs have peered with fascination into other people’s unwanted effects – those velvet-lined mock leather slide collection boxes, their contents carefully inscribed with place, time and cast of characters – and presented a picture of small-town, Brady Bunch America, contrasting them with corporate slide material (for instance 1970s slide presentations from the McDonald’s corporation) and collections made during the Vietnam war.

Like the growing number of artists, curators and designers who are increasingly making use of found photography, the Slide Show Players are both subverting the notion of authorship and acknowledging the power of images dislocated from their context, brought from the private sphere to the public gaze. When the Slide Show Players show us portraits of ‘ordinary’ Americans, in the kitchen, at the workplace, cutting a birthday cake, on holiday, cleaning the car or posing in front of scenic attractions, they are fully aware of the cultural coding which will take place when we see the photographs and listen to the songs. To us, they know, these people will look absurd, parochial, touchingly innocent. They wear polyester, drive station wagons and go to the drive-in. Like real-life citizens of Pleasantville (from the 1998 film directed by Gary Ross) they live in a magical world of kindliness and plenty, encroached upon only stealthily by corporate barons and distant wars.

In Lenny Gottleib’s Lost and Found in American: The Homefront, Fall, 1968: Family Photos During the Vietnam War, published in 2004, a selection of images from Gottleib’s collection of 30,000 amateur snapshots (all of which were rejected prints from a Boston photo lab) forms another absurd narrative which is presented through vernacular photography. Why are the three women on the patterned sofa all wearing the same holly berry dress? What is the donkey doing in the sitting room? Why is the girl with the dark hair wearing an outsize tin of Campbell’s soup? The photographs are untrammelled, unashamed, mawkish, hilarious and endlessly melancholic. They show America at home, America in its innocence, small-town USA untroubled (for now) by the foreign ambitions of its government. When looking at vernacular photography, we construct our own narratives without the constraint of reputation or knowingness of the photographer.

The use of found photography is not new in contemporary art and culture. In 1977, the London artist Dick Jewell self-published Found Photos, a collection of photographs that Jewell had found abandoned around passport photo booths in English cities. Found Photos, in its small, almost hand-made edition, became an important part of the vocabulary of curators and photographers who were already impatient with the US-centric system of master photographers, lavish monographs and curatorial elitism that had inhibited the growth of ideas around vernacular photography.

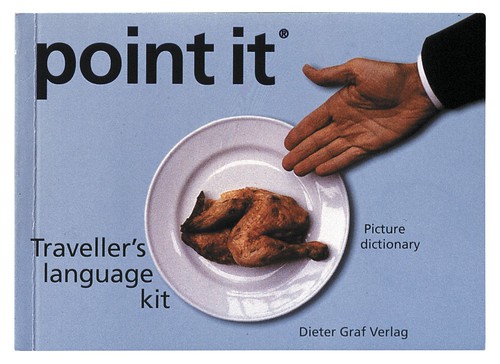

Below: cover from Point It: A Picture Dictionary. Dieter Graf, 1992.

Top: Found Photos by Dick Jewell, 1977.  In recent years, we have begun to refer to the kinds of photography which fall outside the traditionally ‘authored’ as ‘vernacular’. Though this is something of a catch-all, often taken to include photographs as far apart as collections of Victorian carte de visite, family snapshots, photographs found in the street and discarded corporate archives, it has given these kinds of photography a particular identity, and, more importantly, has given vast collections of previously undervalued material a new currency across a wide field of creative work. Vernacular photography is important because it is open to any kind of interpretation. It can be refashioned, re-imagined, resequenced, made into a multitude of different stories. Photographs and assemblages of images made for a particular market can be reinterpreted in the light of cultural knowledge and their meaning can be radically changed.

In recent years, we have begun to refer to the kinds of photography which fall outside the traditionally ‘authored’ as ‘vernacular’. Though this is something of a catch-all, often taken to include photographs as far apart as collections of Victorian carte de visite, family snapshots, photographs found in the street and discarded corporate archives, it has given these kinds of photography a particular identity, and, more importantly, has given vast collections of previously undervalued material a new currency across a wide field of creative work. Vernacular photography is important because it is open to any kind of interpretation. It can be refashioned, re-imagined, resequenced, made into a multitude of different stories. Photographs and assemblages of images made for a particular market can be reinterpreted in the light of cultural knowledge and their meaning can be radically changed.

One example of this is Point It, a picture dictionary for travellers, originally published by Dieter Graf Verlag in Germany in 1992. Graf, an architect and ‘a fanatic traveller’, photographed over a thousand objects, many of which belonged to him, including complete breakfasts, dinners, photographic equipment, toiletries, underwear, sewing kits, bedding, cleaning materials and electrical parts to make a ‘Travellers’ Language Kit’. Point It can be found in the small counter-books section of many major museums and art galleries, and has become a vernacular photography cult book, with its echoes of training manuals, travel books, wildlife journals and children’s picture books. It became popular with a sophisticated audience not only because of its knowing naivety, but also because of our attachment to the kind of publications (home improvement magazines, Ladybird How to Read books, The Home Doctor) which expressed not only innocence but also parochialism, insularity and a nationalist ethic. Our delight in these books (which Point It reinforces) is partly because we have escaped the narrow confines of postwar society which they epitomise. In Michael Landy’s installation Semi-detached at Tate Britain (2004) a full-sized replica of the artist’s family home was accompanied by a slide show of photographs from Do-It-Yourself manuals owned by his father, expressing both longing for the past and exultation at having escaped it so completely.

Photographers, artists and curators have been working with vernacular and found photography since the photographic renaissance of the 1970s. The 1970s and 80s also saw a revived interest in snapshot photography, spearheaded by curators such as Brian Coe at the Kodak Museum, Colin Ford at the newly opened National Museum of Photography, Film and Television in Bradford and the artist Jo Spence, who interrogated the meaning of the family album.

In the US, the Visual Studies Workshop, headed by Nathan Lyons, was renowned for its eclecticism in the collection and discussion of photography. The discovery by Peter Miller and Julia Scully of many thousands of photographs by Arkansas studio photographer Mike Disfarmer in the mid-1970s resulted in the publication of Disfarmer: The Heber Springs portraits, 1939-1946, a book that alerted curators and photographers to the importance of post-1930s studio photography. Though Disfarmer was only one of many small-town photographers photographing citizens and soldiers during World War ii, and though his methodology was as far removed from snapshot photography as it is possible to be, Disfarmer immediately became the principal representative of ‘naive’ vernacular photography among a sophisticated US photographic elite. So much so that in 1996, Twin Palms in the US published a luxurious case-bound edition of Disfarmer’s photographs which soon became a collector’s object and placed the photographer once more at the centre of photographic interest. The embrace of Disfarmer by the luxury photography market brought him to the attention of a new generation of curators, editors and creatives and counterbalanced the fashion / street documentary chic that by the mid-1990s had become the focus of attention for many across the visual arts sector. Disfarmer’s work, and the vernacular photography which it represented, was seen to have an honesty and a purity which the systematic recycling of images and genres in both fashion and documentary photography seemed to lack.

In Europe, interest in found and vernacular photography grew during the late 1980s and 90s. Operating away from the art mainstream was German artist Joachim Schmid whose work was first shown in England in the 1994 Barbican Art Gallery exhibition ‘Who’s Looking at the Family’, together with work from Lancashire Constabulary’s ‘scene of crime’ files and photographs bought at Brick Lane Market in London. Schmid’s major series of found photography, ‘Pictures from the Street’, has been ongoing for the past twenty years. In Bilder von der Strasse, (Edition Fricke &Schmid, 1994), a selection of photographs from his archive appeared in a limited-edition book, bound in recycled card that was itself made up of the fragments of images and texts. He founded the ‘Institute for the Reprocessing of Used Photographs’ and received many thousands of donations. After selecting the pictures he wanted to use (often reassembling them into series – photographs of tv sets, chickens, dogs, sunsets, etc.) the unwanted ones were discarded, recycled into Berlin’s rubbish. He has recently begun to assemble a series of photographs made from discarded negatives by portrait photographers working in the city of Belo Horizante in Brazil. Though Schmid himself is still something of an underground figure, his influence within powerful creative groupings has been enormous. His work is backed up by a vigorously intellectual approach to the meanings of photography, to the art world and to notions of reputation.

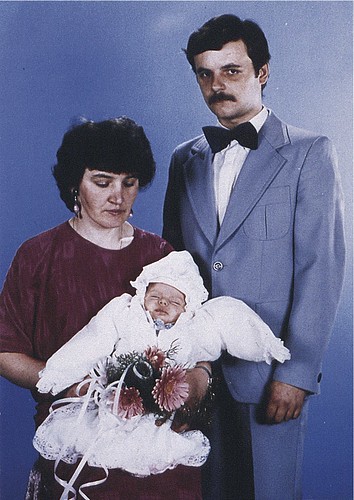

Like Schmid, Alexander Honory also uses the mock institution to define his work with found photography. His ‘Institute of Modern Family Photography’, based at his studio in Cologne, was founded in 1979. Honory has collected photographs of christenings and holy communions, made by studio portraitists, that he found in flea markets. In the photographs which he finds (most likely to be the studios’ out -takes), none of his subjects is smiling and the family groups are grim-faced. In his book work, Raum mit Photos, (1993), Honory dispenses altogether with the photographic image, using words to describe each photo – for instance ‘Thirteen Women, table, white tablecloth, glasses’ – in a long catalogue list.

Below: from the series The Found Image by Alexander Honory, 1989. Honory’s found photos, enlarged to many times their original size, were also included in the 1994 exhibition ‘Who’s Looking at the Family?’.

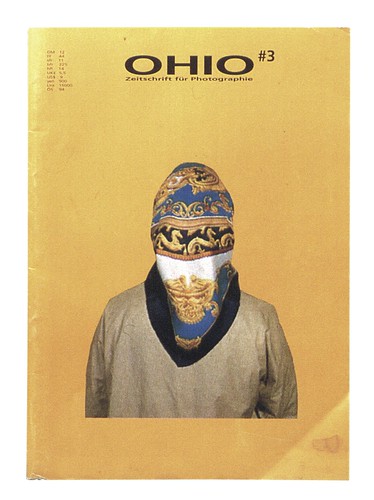

Interest in the vernacular from groups and individuals working within visual culture has been articulated by the publication of a group of magazines which include FOUND in the US, Ohio in Germany (edited by Stefan Schneider, Jorg Paul Janka, Hans-Peter Feldmann and Uschi Huber from 1994), and Useful Photography, edited from the Netherlands by Hans Aarsman, Claudie de Cleen, Julian Germain, Erik Kessels and Hans van der Meer.

FOUND magazine, based in Ann Arbor, Michigan and now in its third issue, is dedicated to the collection and submission by its readers of found material which has included ‘love letters, birthday cards, kid’s homework, to-do lists, ticket stubs, poetry on napkins, doodles – anything that gives a glimpse into someone else’s life. Anything goes’. Photography is central to FOUND magazine, and contributors title the photographs they submit and describe where they were found: ‘Recovered from a dump in New Zealand (picture of a roadside picnic)’. ‘I found this on the street in Milwaukee in the late seventies. There are shoeprints on the back. My guess is they’re sisters (picture of two young girls).’ The magazine is highly interactive with its audience, organising FOUND roadshows in different us cities and setting up street teams.

FOUND’S low-tech, community-based all-inclusive collecting initially appears to work in direct contrast to traditional magazine practice, involving careful selection of material, tightly themed and controlled. But in fact, FOUND’S agenda, like that of the ‘Trachtenberg Family Slide Show Players’, collector Lenny Gottleib and Useful Photography (to name only a few of the increasingly sophisticated players in the ‘found’ arena) is, in fact, as controlled as any magazine in the mainstream. Its constant theme is chaos and dislocation, fragments from a disordered and melancholic society. FOUND is as depressing and disconcerting a read as you could find anywhere. It presents a dismal narrative of a country preoccupied with debt, personal anxiety, addiction, fear and dislocation. In the recent anthology: FOUND: The Best Lost, Tossed, and Forgotten Items from Around the World (Davy Rothbart, Fireside Books, 2004) interviews are included with ‘finders’: ‘I identify with trash. Understand trash. Emphasize with trash.’ (Lynda). FOUND magazine may say that it’s interested in anything, but its interests are fairly narrow – it is eager for ‘found’ confessions (especially sexual ones), obsessed by anxiety – notes from desperate (and often deranged) people are one of its favourite ‘finds’ – and it specialises in confidences from lonely students, obsessionals, deserted children and, above all, the isolated and the desperate.

Below: Useful photography magazine, no. 1. The first issue. Edited by Hans Aarsman, Claudie de Cleen, Julian Germain, Erik Kessels and Hans van de Meer.

On the cover of issue no. 1 of Useful Photography (first published in the late 1990s), are photographs of three men wearing check work shirts. They are posing, possibly for a catalogue. Inside the magazine is a vast miscellany of photographs from corporate and entertainment archives, DIY manuals, safety guides and jewellery catalogues. There is a double-page spread of a photograph of a model railway, a selection of Perspex stands, an electric drill in a case, a collection of birds’ eggs, racehorses, filing cabinets, office furniture carpets, shelves, snake trainers, safety masks and a selection of soft porn. In a recent lecture at the annual photo festival in Arles, Hans Aarsman described how he renounced photography because there were already so many photographs in the world. Without a doubt, the images assembled in Useful Photography no. 1 represent every genre of photography, from fashion through to natural history. Useful Photography aims to subvert the dominance of art market / editorially driven photography, and also to acknowledge the power of the kinds of photography that surround us in everyday life – from the store manager’s portrait in the local supermarket to the illustrations in a holiday brochure. The editors of Useful Photography know that these images will make us smile at the absurdity of both their content and their inclusion in a magazine made by art photographers and ‘creatives’. That we will grasp the meaning of the compilation is understood, that we will bring our own knowingness of the vernacular – of the catalogue and the training manual – is implicit.

Ohio magazine attempts something rather different. Though appearing at first sight to be a collection of found and vernacular images, the photographs are in fact a combination of work by fashion and art photographers (including Craig McDean and Andreas Gursky) and vernacular material. One section purports to be the work of three generations of professional photographers belonging to the Gursky family (including Andreas) while another consists of portraits by the Surrealist Claude Cahun. Unlike Useful Photography, Ohio does not let us draw easy conclusions about the status of the vernacular – if we do not consult the picture credits, we would be in danger of dismissing a Gursky photograph as yet another corporate scene-setter, and Cahun’s work could simply be the zany antics of a fetishistic dresser-up.

If there is a genesis of these magazine compilations, it perhaps lies in the work of art director Tibor Kalman on Colors magazine from 1991 to 1995. Benetton’s lavish free magazine was aimed at a young, international audience to whom reading, to quote Kalman, ‘was an endangered pastime.’ Kalman ‘thought that the magazine should be purely visual … I believed it was necessary to figure out a way to tell a story with pictures – to invert the usual relationship between words and images. And since it was a magazine aimed at young people all over the world, it had to be as relevant to a teenager in Manila as it was to one in Berlin or Cape Town … we only did articles about things which could be relevant everywhere – like snacks, garbage or haircuts. It’s what I like to call “contemporary anthropology”, that quality of life on the planet.’

Kalman’s issues of Colors took simple themes and universalised them, discussing, through compilation, ideas about globalisation, race, youth culture and the environment. Though Kalman was no longer editing Colors when the ‘Animals’ issue was published in Spring 1997, his influence was still evident. The photo spreads included inbred animals (such as the hairless Chinese Crested dog and the Barb pigeon, bred with a beak so large that it has difficulty seeing its food, to animals (including sheep) that feed on urban garbage tips. The issue contained two double-page spreads of photographs of fly swatters from across the globe, a double-page spread of roadkill and ‘Shit!’ showing four pages of photographs of animal dung, from the dinosaur to the dung beetle. Colors presented serious issues – animal exploitation, animal nutrition, pest control – as absurd concepts, as popular culture, and had it not been for the advertising campaigns from Sisley, Renault, Benetton and other high-value clients running through the issue, it would have been impossible to identify Colors as the product of a fashion company. It was Kalman, in his work on Colors, who promulgated the concept of globalisation through the presentation of the ordinary, through an examination of the kitsch nature of international commerce. Colors was an eccentric assemblage of ‘found’ materials, made special by the context in which they were presented, much as the photographs in Useful Photography emerge iconic when separated from their vernacular context.

Below: Ohio magazine no. 3 using found and vernacular photography alongside the work of Andreas Gursky, Craig McDean and Claude Cahum.

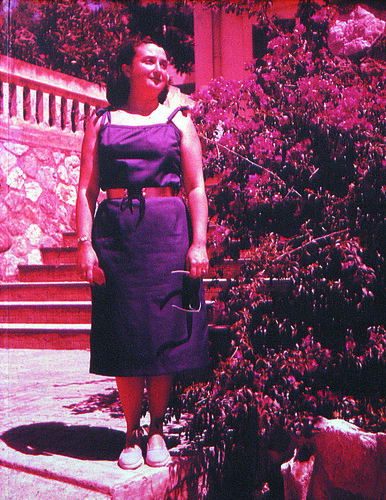

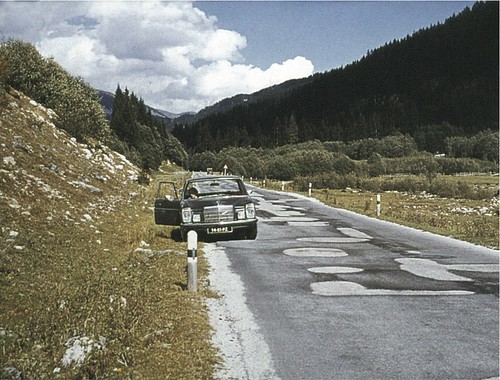

In 2001, Erik Kessels, co-director of the KesselsKramer advertising agency in Amsterdam, published In almost every picture, comprising pictures from an album found in a Barcelona flea market. They were taken by a husband of his wife from 1956-68. Many of the photographs were taken on holidays or on journeys along the Spanish coast. We see her in a leafy garden in Cap-Roig in 1958; at a snowy border crossing in Andorra in 1965; on the beach in Tamarin in the 1960s; in front of a sailing boat in Estartit in 1957. Some of the pictures have faded with time and become infused with the rosy glow of magenta, others have assumed the green crispness of ageing prints. In the end piece of his book, Kessels writes: ‘And now we see the pictures in a way that was never intended. We have the chance to look inside a private collection of private memories. And, in so doing, our memories, or ideas for Their memories, overlap, overwhelm and extend the existing memories in these images, these moments recorded on film …

‘What we photograph today can have continued meaning in a time and place somewhere else, to someone else. What we then find is that we are all involved in every moment. We are all somehow included in what happens to all of us. We are collectively having lives, memories and futures.’

Though found and vernacular photography has existed at the margins of collection and curation for many years, there is evidence (partly perhaps because of the mainstream interventions of figures such as Erik Kessels) that it is rapidly becoming more central in contemporary visual culture. That the KesselsKramer agency has been responsible for the publication of a new volume of work by Joachim Schmid as a free-of-charge book to be circulated within the industry and within the cultural community is an important indication of the encompassing, by vanguard corporate enterprises, of an essentially underground outsider.

In the 2004 anthology Anonymous: enigmatic images from unknown photographers (Thames and Hudson), Robert Flynn Johnson writes: ‘The protective feelings that people traditionally have towards their family photographs makes the discovery of such photographs in a flea market disturbing. Often dumped haphazardly by the hundreds into cardboard boxes, their presence there is both heartbreaking and mesmerising. Like slowing down to see a car wreck, there is a feeling that one should not be looking.’

Below: In almost every picture no. 2. Edited by Erik Kessels.

Such musing is perhaps indicative of the sea-change that has overtaken our viewing of visual culture. What had seemed so certain just a decade or two ago – the democratic qualities of photography, the permanent reproducibility of the photographic print, photography’s status as objective observer, now seems strangely old-fashioned, as the art market absorbs photography into a commercial system which insists on limited numbers of prints, proved provenance and a collectors’ market. The emergence of found and vernacular photography as subjects worthy of both study and collecting has brought photography back into a common ground of culture, available once more to everyone.

The evidence of this can be seen on the Internet, and in the proliferation of found and vernacular photography websites. While book publishing is an expensive and time-consuming process, the posting of large numbers of images on a website is virtually cost-free. The Internet has provided a conduit for the exchange of images and ideas around found and vernacular photography which is instant and flexible. Sites such as Time Tales, set up by photographer Astrid van Loo and designer Dirk Dijman in the Netherlands, is described as ‘a small museum of sorts; lost lives captured on film from all over the world.’

The website Look at Me contains 447 pictures ‘either lost, forgotten or thrown away.’ On Object not Found, rescued albums and loaned collections are illustrated, including the ‘Cooks Hill Book Collection’ (of photographs found in secondhand books), and the ‘Woozy Collection’ of found photo fanzines.

Though increasingly used by commercial organisations as a way of expressing ‘difference’, found and vernacular photography still occupies a flexible and bohemian space in the cultural community. As ‘authored’ photography has become part of the art market and photographers are increasingly bound by the rigid rules of the gallery and the collector, ‘found’ photography seems to defy commercialisation. It also defies notions of privacy and ownership. With the new generation of camera phones and digital cameras, everything can now be photographed and rapidly disseminated via the Internet and personal privacy could soon become an old-fashioned concept. Compilations of the more ‘edgy’ or titillating images can only be just around the publishing corner.

Discussions of photography have always been loaded with questions of ethics, and photography itself is always discussed in relation to its meanings and implications. It is a powerful, even dangerous medium which exposes both truths and lies. When we look at photographs from the past – for instance in Gottleib’s Lost and Found in America, in the Slide Show Players’ AV presentations and in Erik Kessels’s In almost every picture, we are looking not so much at history, but at history reflected through our own cultural prisms. The message of the album which Erik Kessels found in a Spanish flea market seems to be clear enough, and the symbiosis of adoring husband, smart wife and the poetry of photography are stressed by Kessels – but who knows what lies beyond the images? A second, equally compelling volume of In almost every picture shows the photos of a disabled woman who took holidays by taxi. The confidence of Kessels’s bravura approach to publications leads us away from the questions we might well ask about the journey of such albums from private document to public spectacle.

Below: In almost every picture no. 2. Collected and edited by Erik Kessels and Andrea Stultiens.

When the publication of found and vernacular photography moved (relatively recently) outside the spheres of photo historical scholarship or artists’ production and was taken up by major figures inside the photography and advertising world, the implications of its wider dissemination became clear. Most ‘commercial’ users of found photography issue disclaimers which offer to pay reproduction fees to photographs used, should their owners come forward. However, beyond this, there are other issues, of permission and of privacy, which the new users of the found and vernacular image, and those who comment on them, will have to begin to address.

In the past decade, many people involved with photography have turned to the found and the vernacular to present a different view of social history. The growing suspicion of photojournalism – how many pictures were posed? how many subjects were paid? – has led us to take up a counter-position. If photojournalism is directed and structured (and thus artificial), then found and vernacular photography must somehow be the opposite, truthful in its innocence and naivety.

When two children of consumerist, contemporary America find themselves mysteriously transported to the uneventful streets of the small town of Pleasantville, they discover that the price to be paid for being part of an American idyll is a high one. They find themselves living in a society where books have no words or pictures, where streets lead nowhere, a black-and-white world in which there is no risk, no adventure. In our rush to find a Pleasantville in visual culture, to discover innocent images without motives, we must perhaps be wary of becoming a part of yet another cultural fiction.

First published in Eye 55, Spring 2005.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. Eye 83 is out now, and you can browse a visual sampler at Eye before You Buy.