Spring 2010

Machine head

Fritz Kahn commissioned illustrators to realise his surreal pedagogical vision – mechanical metaphors for the human body.

Images of the body interpreted as a machine have always exerted a powerful fascination....[But] images that once looked futuristic, expressing the technological dreams and aspirations of their time, seem dated and even comical, measured against our own command of technology and the biosciences. But this in no way diminishes their appeal.

The factory man who forms part of Paolozzi’s collage city is the work of a Jewish German gynaecologist by the name of Fritz Kahn (1888-1968), who was once renowned as a science writer. A few images from his books circulate on the internet, where they have caught the attention of web-trawlers interested in extracting bizarre anatomical pictures from the archives. Der Mensch als Industriepalast (‘Man as Industrial Palace’) was issued as a poster enclosed with the third volume, published in 1926, of Kahn’s five-part Das Leben des Menschen (‘The Life of Man’). The complete publication ran to more than 1600 pages, with around 1000 illustrations and 150 colour plates.

Kahn’s aim was to express the complexities of the body through visual narratives that anyone could relate to and understand. He and his publisher, Franckh’sche Verlagshandlung of Stuttgart, developed a form of anatomical visualisation based on metaphors and analogies drawn from mid 20th-century life and the latest developments in technology.

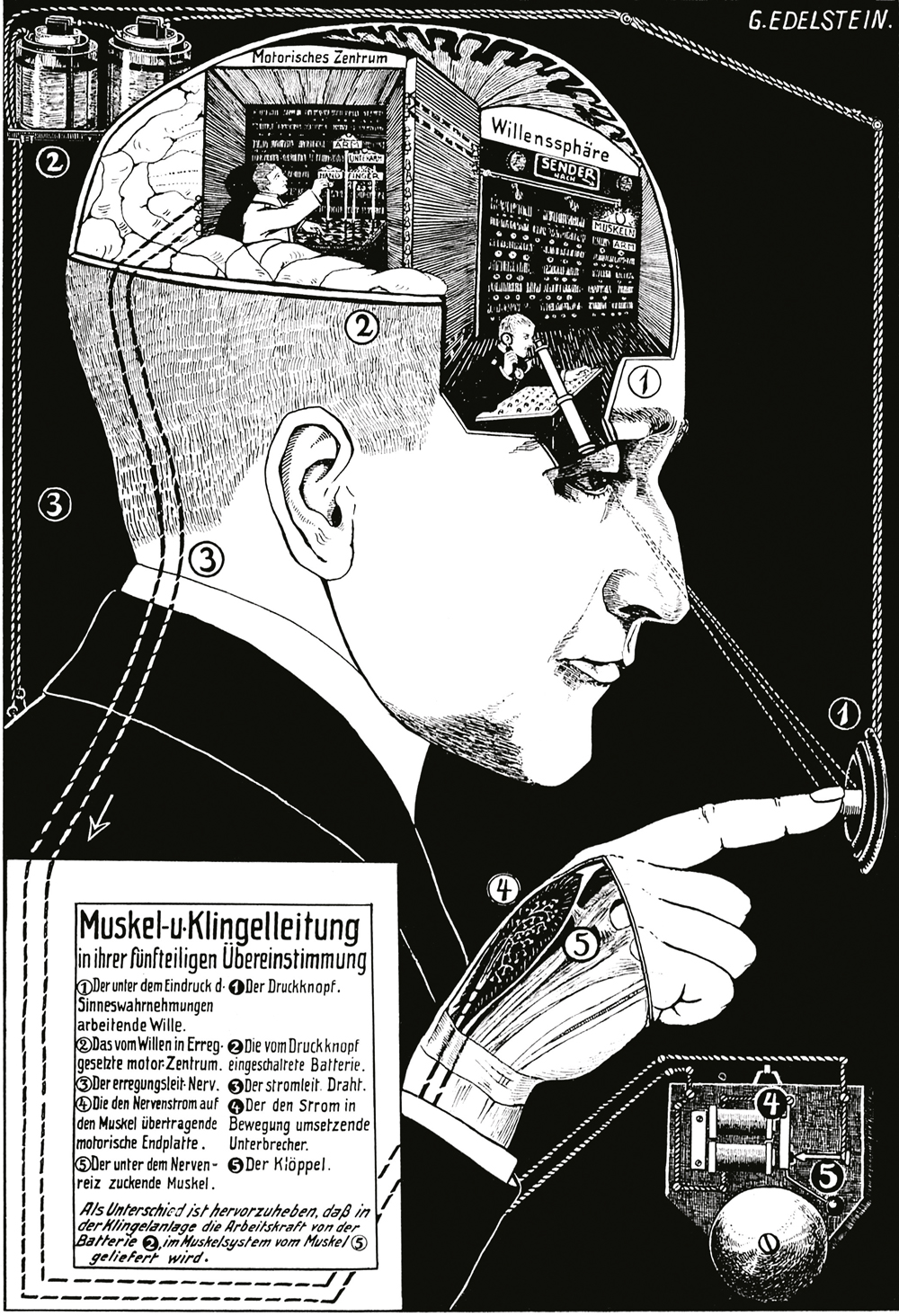

In style, the illustrations reflect the artistic movements and visual trends of their era, notably Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), Art Deco and Surrealism. The man with a cutaway head pressing a doorbell in Das Leben des Menschen ii (1924) is a conceptual relative of the man with a collage of machine parts for a brain in Raoul Hausmann’s Tatlin at Home (1920). The ‘fairy-tale journey along the bloodstream’ images in the same volume recall both the naturalist Ernst Haeckel’s sea creature studies and the biomorphic imagery of Surrealist painting.

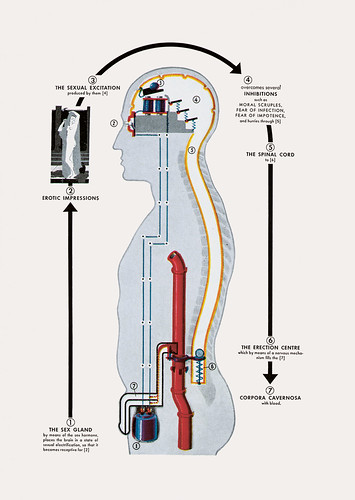

‘Technical-schematic presentation of the male erection system’ from Kahn’s Our Sex Life, 1939.

Top: Illustration from Fritz Kahn’s Das Leben des Menschen II, 1924.

Kahn executed none of these illustrations: the doorbell man has a visible credit to G. Edelstein, the fairy-tale journey pictures to Arthur Schmitson. Uta and Thilo von Debschitz, authors of a new study of Kahn, list 21 other illustrators who produced images for the books; there were certainly more. Since Kahn was unable to draw, he would submit his ideas in the form of instructions and sketches, which were then worked up and finished by illustrators and graphic artists. From the late 1930s, Kahn asserted his ownership of the visual concepts that won him international acclaim with an ‘fk’ copyright signature placed on the image. As the historian Cornelius Borck suggests, these cases of graphic teamwork are best understood as an example of the ‘collective and institutional production of authorship […] “Kahn” is the product of his times’. His trademark was an early form of branding and some of the images were later re-used.

In 1933, anti-Semitic legislation forced Kahn to close his practice and flee Germany for Palestine. In 1938, the Nazis put his books on a list of harmful writings and the police destroyed copies of Unser Geschlechtsleben (1937). An English edition, Our Sex Life, was published in London the following year, by which time he was living in Paris. In 1941, helped by Albert Einstein, Kahn moved to the us and set up home in Manhattan, then later in Long Island. More books, publicity and translations followed.

The reductionist thinking practised by Kahn was already being questioned even while he was at work. One elementary problem, as Borck points out, is that the illustrations contain the evidence of their own failure as explanations of how the body operates: they rely on little technicians, miniature versions of that same body, to perform biological functions. ‘It is precisely in their ambivalence that Kahn’s images show the limits of technological enlightenment and the promise of humanity that was once attributed to technological progress,’ writes Borck.

The illustrations also bear witness to some familiar, though historically inevitable, gender stereotyping. While the male body, generally preferred by Kahn as the medium for anatomical demonstration, is rendered as a functional machine, his visualisations of the female body can be sinister or monstrous.

If the outdated image of the clanking, power-plant man-machine persists in the age of the cyborg manifesto and the prosthetic implant, it is the omnisexual erotic possibilities that appear to engage many viewers now. In a series of ads by Young & Rubicam for River North Chicago Dance Company, lithe athletic bodies are peeled open to reveal squads of dedicated, diminutive workers toiling in cavities of bone and tissue. Meanwhile, more than a few bloggers drew approving comparisons between Kahn’s still beguiling inventions and a set of images by Spanish illustrator Fernando Vicente, who paints pictures of women on top of old car diagrams, cheerfully fusing cold steel and warm flesh.

Uta von Debschitz and Thilo von Debschitz, Fritz Kahn: Man Machine (Springer, 2009; fritz-kahn.com).

See also: Cornelius Borck, ‘Communicating the Modern Body: Fritz Kahn’s Popular Images of Human Physiology as an Industrialized World’ in Canadian Journal of Communication, vol. 32 no. 3, 2007.

Cover of Der Mensch, 1939

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, London

First published in Eye no. 75 vol. 19 2010

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.