Winter 2008

Magic box: craft and the computer

Marian Bantjes

Matt Pyke

Karsten Schmidt

Build

William Morris

Walter Crane

Casey Reas

Ben Fry

Long undervalued as a poor relation of art and design, craft is central once more. Essay by David Crow

During my student days in Manchester, there was a deep rivalry between students of design and fine art, and we were specific about our differences. But we were united in refusing to describe ourselves as craftsmen. Craft practice, associated with folk art, tradition and the past, was regarded with some disdain.

Many years later I am head of design in the same art school. I am aware now of the history and character of the Manchester School of Art, founded on the values of the Arts and Crafts movement, led at one point by Walter Crane. The intervening twenty years have drawn me to ‘crafted’ solutions. By this I mean work bearing the mark of its maker, sitting alongside earlier work as part of the maker’s journey of discovery. Yet in some areas of visual culture, the term ‘craft’ is still used pejoratively. In a world where ideas are the prime currency and craft skills can be hired, craft and ‘concept’ are seen as mutually exclusive, and craft practitioners will only be funded to continue their work if they call themselves ‘artists’ or ‘designer makers’. A valuable area of creative process risks being overlooked. Unless we challenge this, by developing a new discourse around it, we may consign everything that craft stands for to the archive, forever.

Dictionary definitions of craft generally refer to ‘weaving, carving or pottery’, folk-art activities that involve doing or making things with your hands, in a ‘beautiful’ way. Key to the way we talk about craft practice is this presence of the hand. The hand is an important metaphorical signal for the presence of the individual in craft, and is central in the symbolism surrounding the historic tension between man and machine, and more recently between global and local culture.

Mechanical prejudice

Craft has an image problem. This was acknowledged as far back as the eighteenth century; Diderot’s Encyclopaedia (1751-80) both confirms the low respect paid to artisans and the author’s puzzlement at this: ‘craft. This name is given to any profession that requires the use of the hands, and is limited to a certain number of mechanical operations to produce the same piece of work, made over and over again. I do not know why people have a low opinion of what this word implies; for we depend on craft for all the necessary things of life … I leave to those who have some principle of equity to judge if it is reason or prejudice that makes us look with such a disdainful eye on such indispensable men.’ In these terms, craft is no longer a practical trade; and despite the Arts and Crafts call for objects to be both functional and beautiful, craft is seldom accepted as serious art.

Nepenthe, textile hanging, 2 x 2.5m, by Alice Kettle, 2008, made using a variety of mechanical and computerised embroidery equipment. Kettle employs her ‘ignore the default’ motto by deliberately interfering with the standard machine settings to create unusual results.

Top: Robert Hodgin’s Solar, with lyrics (2008) uses processing to generate an animated visualisation of the Goldfrapp song ‘Lovely Head’. The lyrics were overlaid on the animated visuals as a synchronised moving text.

Before organised industry, everything was craft. The medieval guilds brought status to artisans, and towns and cities were built on the commerce that they generated. Then the Renaissance introduced the intellectual separation of fine art and practical craft; and artisans came to be seen as skilled manual workers, whereas artists became ‘cultural’ workers. But in the age of the machine, as industrialisation came to dominate in the nineteenth century, there was less and less place for the hand.

Inventions such as the Schiffli embroidery machine transformed the work of the hand into mechanised labour, making simultaneous multiple-stitched copies of a design an artist had produced. The motto of the Hewetson family (original owners of the Schiffli machine now housed in Manchester School of Art) was ‘I Fear not the Light’ – but for all their optimism, the new technologies also brought pollution, poverty and disease.

In the nineteenth century, mechanisation was much criticised, probably most vigorously by the Arts and Crafts movement (1860-1915). Factory production and the machine were denounced as a tyranny, in favour of individual workshops, skillful craft and wholesome human endeavour – essentially a crusade against commerce, as much about taste as egalitarianism. The movement’s romantic revival of medieval craft was grounded in what was seen as the truth of natural materials and most importantly in the ‘beauty and truth’ of the individual. If William Morris was the figurehead of the movement, then John Ruskin was its inspiration: ‘For it is not the material, but the absence of human endeavour, which makes the thing worthless’ (Seven Lamps of Architecture, 1849).

One lasting principle of the movement is the claim that art has a place outside the gallery; that art can be found in things that are useful. Industry was a ‘beast without hands’ that made dull and monotonous objects (and, as Marx later suggested, would do untold damage to the human experience). Hands were celebrated as capable of probing the world, bringing a unity of working and learning. No machine could replace the sensitivity of hands. Craft practice became synonymous with individualism and integrity.

From the early twentieth century, this stance began to be reversed. The industrial world was increasingly associated with radical political change, the factory with the future. Craft was more and more seen as dependent on tradition, and craft workers as resistant to change. Modernism positioned craft as the ‘other’ form of art, as Sue Rowley notes (Reinventing Textiles, 2004). By the second half of the twentieth century, the appreciation of art was becoming purely an intellectual exercise, as opposed to a sensual one. In the information age, what you see is what you get. In the art ‘factories’ of such artists as Warhol, Koons and Hirst, hands – essential to the process yet lowly in the hierarchy, hired-in – seemed almost irrelevant. Where signification is primary, the tools and processes associated with craft signify little more than nostalgia.

Still from ‘New Shoots’ (2007), an animated sequence for the Channel 4 television series, uses literally growing typography, made up of millions of particles. Concept, algorithms, software development and 3D rendering by Karsten Schmidt of PostSpectacular.

Craft has been rooted in particular tools and associated techniques, each defining its respective practice, as have the design disciplines, historically, and much of art: painting, printmaking, photography, typography and so on. But today anyone calling themselves a graphic designer or an artist will likely employ a wide range of tools and media, and quite possibly engage with the ideas surrounding each practice and its inherent ‘craft’. Yet despite the cross-influence of areas of cultural production on one another – or because of it – the habit of defining practice in terms of the use of tools is not helpful in the information age. This is mired in a discourse that has been static since the sidelining of the Arts and Crafts movement a hundred years ago. Nor does it recognise the cross-disciplinary nature of contemporary practice.

Unpredictable play

Craft practitioners such as Alice Kettle talk of the ‘performance’ of craft, and of ‘curating’ input from assistants or apprentices – not as a mechanical input but to set parameters and allow the unexpected to surface. Artists and designers have always approached technology with this eye for the accidental: witness Vaughan Oliver’s creative play with photomechanical transfer camera and old chemicals. This approach has its contemporary equivalent in Robert Hodgin’s use of Processing. Hodgin allows programmed elements to interact in unpredictable ways, yet maintains control over the chaos that results from multi-dimensional work with multiple parameters. His Solar, with lyrics (2008), a self-initiated work accompanying the Goldfrapp song ‘Lovely Head’, expertly weaves together data from audio files, text files and beat analysis into a work of elegance and moving sensitivity, rich in texture and atmosphere.

When digital technology arrived in the 1980s, type designers made the accidental a starting point for new ideas. Some, as they became more adept with the new technology, began to intervene in the underlying computer code. For their Python Fonts, LettError (Erik van Blokland and Just van Rossum) crafted a bespoke software engine that generates fonts with a random element integrated into the design. The virtual ‘apprentice’ offers suggestions; the designers choose what to keep and what to discard. As they wrote in the promotional literature for Python: ‘Creative Power comes from writing the code of the filter, deciding how it works, not from using it.’ LettError enthusiastically pioneered the adoption of coding as a design tool. With their typeface Beowolf (1991), they were the first designers to use code to randomise typography. Their aesthetic clearly celebrating the handmade and the physical, LettError harnessed digital technology to create letterforms by art-directing the multiple possibilities programmed into their bespoke software engines. Their latest creation is a new version of their classic typewriter face Trixie (see Eye no. 20 vol. 5).

Trixie HD is a highly detailed typeface capturing the roughness and irregularities of an old typewriter. It takes full advantage of OpenType technology, the latest development in typographic software. Van Blokland used code to generate small dots that function as halftones and smudges when they interact with anti-aliasing on screen or with ink in a laser printer. The huge number of points needed for such detail of resolution could never have been made manually. Trixie HD Pro Heavy, for example, has more than 6.7 million points. Each character has seven alternates, each with its own weight and rough detailing. OpenType switches these around to simulate typewriter type in a way never seen before in digital typography. The type varies in weight, dancing on the baseline, a visible ‘ink and ribbon’ effect.

Digital sweet spots

Curiously, the craft of programming is helping to further traditional craft aesthetics and production in present-day culture. Mimetic Butterflies (2007), an installation for the McLeod Residence in Seattle made by Hodgin and his partners in The Barbarian Group, combines programming with paper-cut craft. PostSpectacular’s Karsten Schmidt, a self-taught ‘artisan programmer’, created an ingenious model (of the words ‘Type & form’) for the August 2008 cover of Print magazine. For this he worked with a biochemical reaction model using vector-based typography, ran the results through MRI scan visualisation and created the final ‘monster’ on a 3D printer.

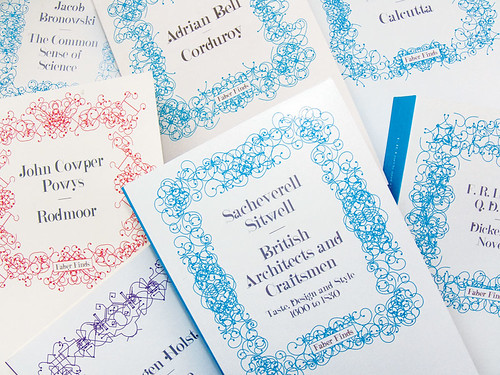

Book jackets for Faber Finds (2008), the UK publisher’s print-on-demand archive service. The ‘design machine’ created by Karsten Schmidt of PostSpectacular is flexible enough to generate an endless number of unique designs, one for every single book in the series. Design templates by Marian Bantjes. Custom font by Michael C. Place / Build. Art direction by Faber & Faber.

Matt Pyke from Universal Everything created mass-produced printed one-offs for the Lovebytes Festival in 2007 (see Eye no. 65 vol. 17). He collaborated with Schmidt to design a ‘creature generator’ that produces thousands of one-off prints on paper. Pyke and Schmidt have recently worked together again on a large-scale digital installation for the Victoria and Albert Museum in London from 21 November 2008 to 1 February 2009. This collaborative philosophy is also a theme of digital craft. Entitled Forever, this videowall installation uses bespoke coding to generate endless animations – based on the physical simulation of a piece of string – which respond to a similarly endless, regenerating audio soundtrack based on sound samples composed by Simon Pyke.

Schmidt and Matt Pyke are key practitioners in a new wave of digital craftspeople whose programming creates design machines that generate large numbers of possibilities around preset parameters. What gives these digital artisans their individuality is the unique combination of these parameters, the combinations they craft and the choices they make representing the artisan’s metaphorical thumbprint. Schmidt sees this exploration of a potentially limitless range of possibilities as a search for the ‘sweet spots’.

Experiment and play are vital in craft practice. Play lets you learn, which is why it still lies at the heart of art and design education. And the computer can very effectively introduce play; digital media, with their instant reversibility and ability to simulate, can withstand sustained experimentation where other formats would disintegrate. Moreover, the digital context can be its own world, beyond the need to mimic physical reality or structure. It supports generative structures based on natural processes but can also evolve its own. Freely experimenting with process, this new generation of designers is fashioning a future for graphic design where craft practice – and the ‘what if?’ question central to it – is integrated into the coding itself. And they are reassuringly ready to share their ideas over the Web, so that others can use these small elements of coding to collage them together in their own way, to create new ways of manipulating digital material.

A 2005 paper by US educator Michael Mateas, Procedural Literacy: Educating the New Media Practitioner, suggests that children should be introduced to computer programming at an early age. He cautions against introducing a new language at graduate level – writing sophisticated stories while learning a new grammar and a new vocabulary is too steep a challenge. ‘Anyone involved in cultural production on, in or around a computer,’ claims Mateas, ‘should know how to read, write and think about programs.’ Armed with this ‘procedural literacy’, designers will no longer treat the computer as a mysterious ‘black box’; we will have authorship, and a richer relationship between coding, design and the audience will develop.

In terms of ‘abstract craft’, some educators worry that students will do what predetermined tools make easy. Mateas’s ‘prison-house of art friendly tools’ gives us what Van Blokland calls the ‘illusion of completeness’ – the idea that anything can be achieved using dropdown menu and toolbox sidebar. There is also concern that literacy in scripted notations comes at the expense of visual literacy. In the institutions, pressure to add further content to the curriculum usually results in focusing more attention on the visual. This is based on the assumption that visual literacy requires education, while procedural literacy can be self-taught, or left to simple training. But such a view neglects the sophistication required to grasp the interplay between technical control and the making of meaning.

Team-based production may be a solution, with designers and programmers working together. In contrast to the older master-and-apprentice set-up, the computer encourages a more democratic structure. Mateas suggests designers and programmers be placed in teams only when each has an understanding of the other’s area of expertise – what Malcolm Garrett described (at Eye’s Forum no.3) as being a ‘jack of all trades and a master of one’. Notable examples include John Maeda’s Computational Aesthetics group at the MIT Media Lab, who generated Design by Numbers (Maeda) and Processing (Ben Fry and Casey Reas – see Eye no 65. vol 17).

At a recent London higher education conference about the (uncertain) future of craft practice in the UK, delegates voiced their concern at craft being defined as a series of disciplines ‘other than’ digital media. Clearly, the use of digital media is essential to the survival of craft practice. The key to achieving a viable curriculum in computing is in recognising that programming – despite its abstract nature – has the properties of a concrete craft practice. I suspect that when the curriculum is designed by educators who have grown up with coding, the computer will become more transparent in our art and design schools. What makes for good virtual craft is not the quality of the technology but the application of our perceptive ability to generate surprises – combining motivation, visual thinking, knowledge of tools and our experience of media.

Cracking open the box

Craft is so often described as a practice surrounding a specific set of materials. But in truth it is less the material that defines the practice as the process of play, experiment, adjustment, individual judgement and the love of a material – any material. Exploring craft through coding, these new digital artisans and designers share the love of material with their counterparts in ceramics or glass or textiles. Their wonderment at the possibilities is infectious and inspirational. Education must look to these individuals to help redefine our relationship with the computer, and to draw attention to the important fundamental values in the ‘traditional’ crafts, too. With the help of the programming community we can ground our graduates in the language of both physical and abstract material, and move from treating the computer as the mystery ‘black box’ to the box of magic it surely is.

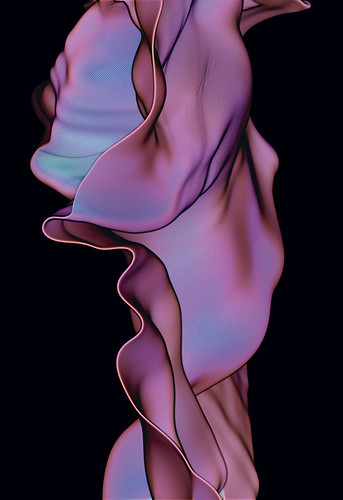

Forever, a generative audio-visual installation displayed on a large videowall in the V&A Museum’s John Madejski Garden, 2008. Created by Matt Pyke and Karsten Schmidt for Universal Everything using sound by Simon Pyke. A custom-developed audio-visual generative system creates and composes music and visuals in parallel. The images – all based on the physical simulation of a piece of string – are combined with about 100 sound samples to weave a sound blanket of patterns that never repeat.

David Crow, head of design, Manchester Metropolitan University

First published in Eye no. 70 vol. 18 2008

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.