Winter 1990

Maps and dreams

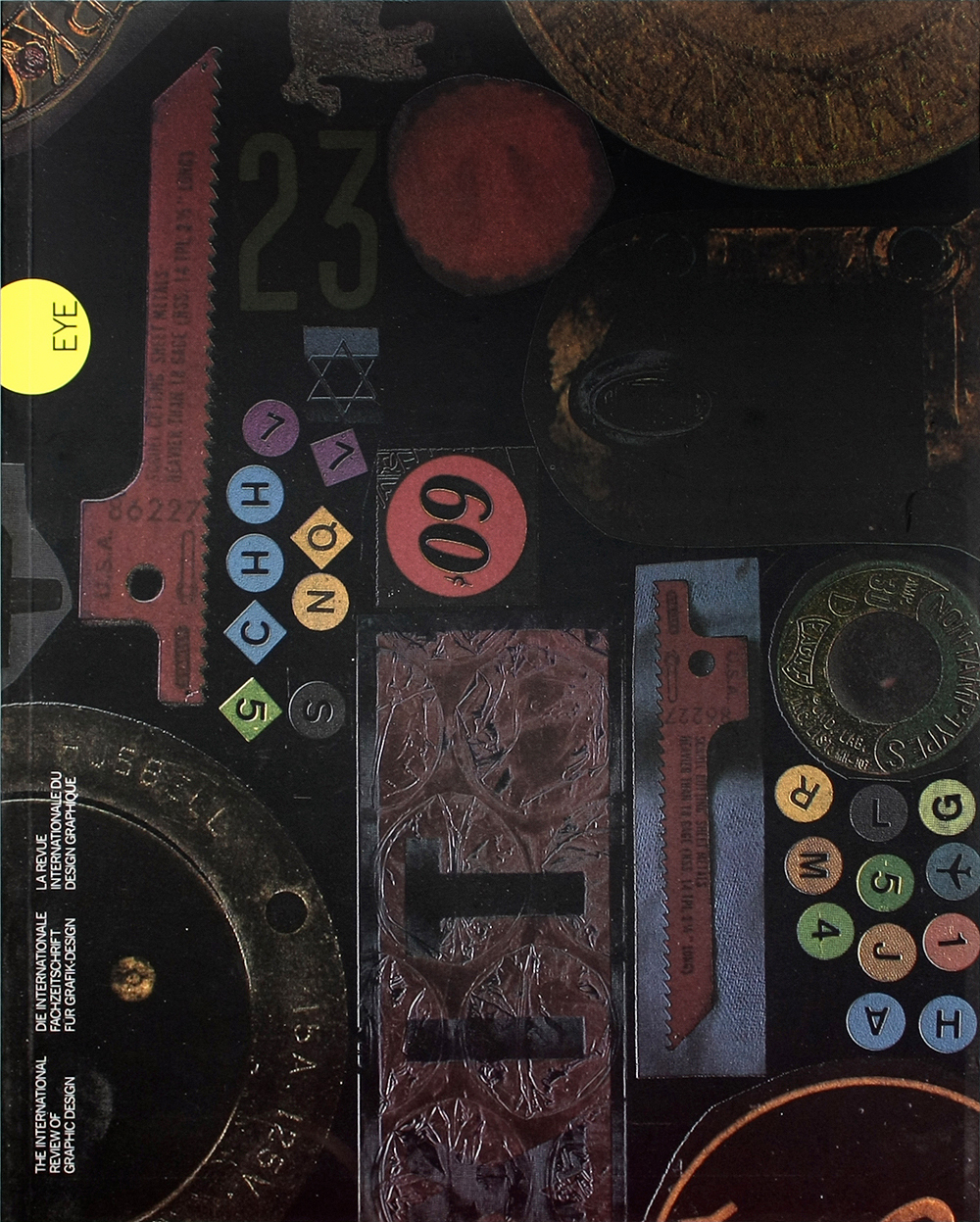

No printing method is too basic for Jake Tilson. Created with photocopiers, his books, magazines and objects are crammed with offbeat invention.

If design at its most insensitive tends to homogenise the visual landscape, then Jake Tilson is waging a campaign to preserve the native and vernacular. In paintings, dioramas, magazine and books fizzing with urgency Tilson struggles to recapture the atmosphere of places, the tactile essence of lost and fading things. It is not nostalgia that motivates him, he says, or some misplaced desire to glorify the seedy, humdrum, decrepit and banal. Tilson simply wants us to see the urban landscape – its buildings, streets and graphics – as they really are.

Tilson trained as a painter at Chelsea School of Art and the Royal College of Art and this inevitably determines his approach to design. What his typography and methods of layout lack in finesse, at least from a purist’s point of view, they make up for in vitality, wit and an eye for the revealing detail. Tilson once observed that ‘a John Bull printing set can have more effect than full-colour litho if used well’. He has gone on to make the rapid, low-cost, readily available print methods that designers usually shun – photocopying, instantprint, even rubber stamping – the basis of his work.

Tilson claims he did not set out to break the conventions of publishing; he just never knew what they were. Inspired, like so many other British children in the 1960s, by the colour and excitement of American comic book, Tilson produced his first ‘magazine’, in hand-drawn multiple editions, at the age of nine. ‘Supermut’ the flying dog was followed a decade later, at the height of punk, by the enigmatically named Laza7, co-edited with other students at Chelsea. But it was Cipher, financed with £150 Tilson found in the street and launched in December 1979, that established Tilson as an independent small press publisher to be reckoned with. By issue four, an edition of 400 copies produced by letterpress, colour Xerox and linocut, Cipher was selling in Germany, Japan and the US, as well as Britain.

Cipher had a sophistication of form and content that set it apart from the explosion of amateur Xerox ‘fanzines’ produced in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Prolifically inventive, Tilson followed it with a stream of hand-made books in photocopy editions varying from ten to 500 copies, in which his habitual themes – time, travel, geography – emerge from compressed science fiction narratives inspired by the writings of William Burroughs and J. G. Ballard. Eight Views of Paris is an eight-collage travalogue using a Metro ticket as a leitmotif. The V Agents is a collage tale of global paranoia and possible apocalypse cast in the form of a spiral-bound sketchpad; The V Agents part 2 continues the story through a series of alphabetical file cards and interleaved images supplied in a polythene bag which recalls the packaging of cheap plastic toys from the 1960s.

In 1985, Tilson’s Woolley Dale Press published the first edition of Atlas, an occasional magazine whose title neatly encapsulates his obsession with mapping, or re-mapping, the world. Atlas has become progressively more assured with each issue. Lacking formal training in graphic design and reprographic method, Tilson has taught himself by trial and error as he goes along. He keeps marked-up samples of typesetting and annotates proof copies with tint specifications so he knows which effects to avoid or repeat. The process of research, commissioning (contributors range from the painter Antoni Tàpies to cartoonist Steven Appleby), writing, design and production is a one-man labour of love. Atlas 3 evolved ‘organically’ from Tilson’s first sketchbook ideas to eventual publication, two years later in 1988, in a trilingual, offset litho-printed edition of 2,500 with assorted hand-applied extras. After all this effort the reader might be inclined to treat the pages of Atlas 3 with some respect. Tilson, however, wants you to take scissors to the magazine and reassemble it: the issue includes a booklet, a paper clockface and a model, all to cut out and construct, and a bag of material for do-it-yourself collages with the ironic title ‘Montage made easy’.

It is this attention to the thematic framework which holds Tilson’s publications together and gives his graphic devices meaning. ‘Unless there’s a content, unless there is a reason for something to be stuck in, it will fail,’ he says. Tilson’s most recent and ambitious multi-volume series, Breakfast Special, presents five views of ‘Mr Emerson’ (a character who reappears in different guises throughout Tilson’s oeuvre) leaving his apartment and entering a café for breakfast in five different cities: Arezzo, Paris, New York, Barcelona and London. These international scene changes provide Tilson with an opportunity to mount a virtuoso exploration of local atmosphere and vernacular detail in which typography (Garamond, Century Old Style, Trump) is as vital to the descriptive effect as the imagery with which it merges. Following Tilson’s usual practice, the photocopied pages of the books are sprinkled with tiny hand-glued Xeroxes, individually applied rubber stamp marks and hand-drawn lines, letters and numbers, fusing in compositions of real delicacy.

Breakfast Special’s carefully controlled pace, its sense of drama and interval, represent a significant step forward for Tilson. Artists’ books frequently misfire as graphic objects because they are conceived in terms of the individual image, with no regard to the image’s place in the sequence. By embracing the idea of an organising narrative – for so long unfashionable in artistic circles – Tilson is able to avoid this problem. Early layouts suggest that Tilson’s next narrative, The Terminator Line, his first hardback book, will weave lines of free-flowing, hand-positioned type into photocopy arabesques of even greater complexity. The book format, says Tilson, continues to offer the greatest challenges to the artist-designer.

First published in Eye no. 2 vol. 1, 1991

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.