Spring 2013

Milan’s anarchic Modernist

Alessandro Colizzi explores the Futurist past of Bruno Munari, the eclectic, prolific designer-illustrator of Mussolini’s Italy.

In the years before the Second World War, the Italian Modernist Bruno Munari (1907-98) worked simultaneously as a painter and an advertising designer trying his hand at a wide array of media: illustration, photomontage, animation, book design, publicity, art direction, exhibition and furniture design. His work, though apparently founded on a fundamental rationality, is enlivened by an anarchic, humorous vein. Yet nowadays Munari is associated mostly with playful ‘illegible books’, work for children and his polemical best-seller Design as Art (Penguin Modern Classics).

This may be because Munari’s early work was made under the Fascist regime, which rose to power in 1922 in the unstable Italian economic situation that followed the First World War. While protectionist policies and state interventions led to a significant growth in production and wider availability of consumer goods and leisure activities, Mussolini’s government, with the support of the church, the monarchy, the armed forces and the industrial establishment, soon metamorphosed into an outright dictatorship, through a series of laws that suppressed political freedom and expression.

Art and design

Munari grew up in the Veneto countryside, where his family ran an inn. At the age of nineteen he returned to Milan, his birthplace, to become a painter, and was soon participating in the Milanese Futurists’ group exhibitions. Advertising design was often the main source of income for artists of his generation. ‘Working as a graphic designer … was my salvation,’ Munari said in the 1980s. ‘While other artists were bound to some dealer … I worked as a graphic designer for magazines. I also did comics, but with a very different sense of humour. I also worked with [the Rationalists] but I was a graphic designer – both to earn a living as well as to have freedom in other areas.’ [1]

Milan was an important cultural centre, a welcoming environment for artists, writers and intellectuals. They were able to nurture the emerging relationship between art and industry in art galleries such as Il Milione; in the editorial offices of Casabella, run by the critic and editor Edoardo Persico and the typographer Guido Modiano, and of Guido Mazzali’s L’Ufficio moderno; in Olivetti’s advertising office on via Clerici; and in Antonio Boggeri’s studio on via Borghetto.

In his early twenties Munari was employed as a sketch artist in the Mauzan–Morzenti studio, an ad agency founded by the French affichiste Achille Mauzan, and began collaborating with the comic-strip artists Carlo and Vittorio Cossio on pioneering animated advertising shorts. [2]

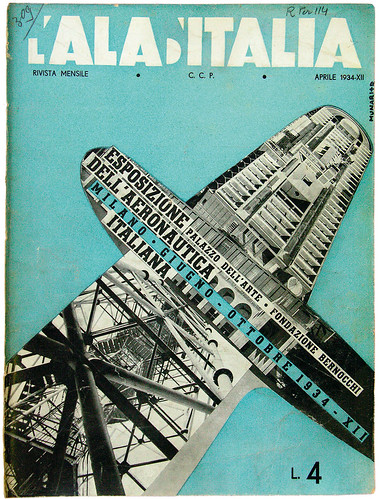

Working as a magazine illustrator, Munari could experiment freely with visual language. His contributions to Futurist publishing ventures such as Almanacco dell’Italia veloce (1930) and Simultanina (1931), and his work for popular magazines (Lidel, Natura and L’Ala d’Italia) successfully transposed the new ‘aeropictorial’ trend into mainstream illustration. The best examples of his mature Futurist style can be seen in the anthology Il Cantastorie di Campari [The Story-teller of Campari](1932) and the tin-litho book L’Anguria lirica [The Lyric Cucumber] (1934).

Cover of L’Ala d’Italia, April 1934.

Top: portrait of Munari by fellow designer Albe Steiner, 1941. Archivi Storici, Archivio Albe e Lica Steiner, Politecnico di Milano. All reproductions © Bruno Munari. Courtesy Corraini Edizioni.

Futurist collaborations

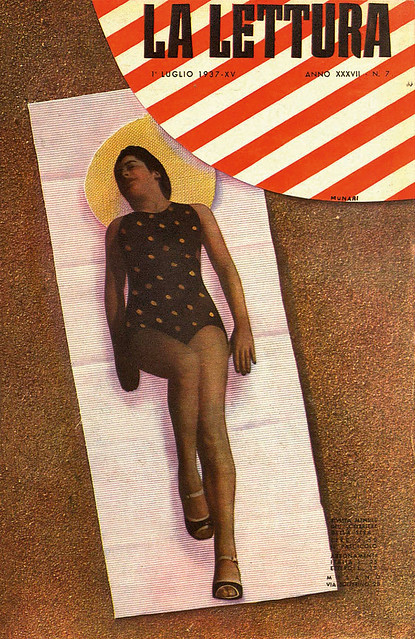

Until 1939, Munari’s work appeared in every edition of L’Almanacco letterario, an annual publication devoted to the literary scene, published by Bompiani. His contributions ranged from comic drawings to collage, photomontage and photograms, all with a distinctive ironic tone. He also explored more conservative visual languages for the covers of La Rivista illustrata del popolo d’Italia – the monthly supplement of Mussolini’s newspaper Il Popolo d’Italia – and La Lettura.

In 1931, together with his fellow designer Riccardo Castagnedi (known by the pseudonym Ricas), Munari set up the graphic design studio R+M, one of the first of its kind in Italy. He had met Ricas a couple of years earlier through Futurist circles. To begin with, R+M’s output had a painterly emphasis, but gradually moved toward a redefinition of the Futurist language through a more concise, abstract approach. The adoption of the photographic collage as their preferred medium set Ricas and Munari’s style closer to Surrealism than to typographic functionalism, and would remain their hallmark until the mid-1930s. Their professional partnership remained flexible, with them signing work both together and individually, until they parted ways in 1937, when Ricas joined the publisher Editoriale Domus.

While Futurism provided his stylistic framework, Munari kept abreast of metaphysical and Surrealist developments through foreign examples reproduced in the trade press. Despite the closed intellectual climate imposed by the regime, artists in Milan could follow advances in international art through foreign publications circulated in selected bookshops and art galleries. Munari’s compositions sometimes show close similarities with Herbert Bayer’s more Surrealist advertising work. [3]

By the early 1930s photomontage was enjoying a degree of popularity in Italy, both as a form of illustration in the press and at exhibitions. Munari used photomontage in his illustration work for periodicals as well as in advertising.

Occasionally, he made celebratory photomontages on propagandist themes, such as ‘Udite! Udite!’ (‘Hear! Hear!’), a long sequence published in L’Almanacco antiletterario (1937). Later in the decade his interest in photography focused on Surrealist collage, inspired by Ernst, and on cinematic sequences.

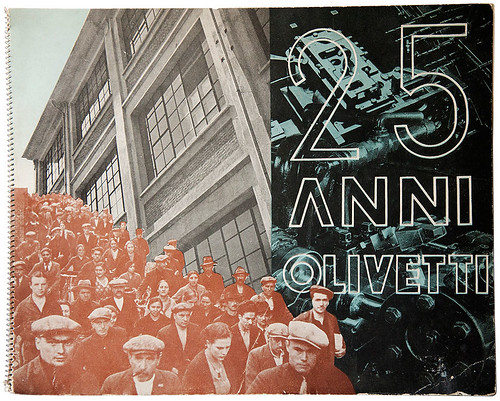

R+M’s clients included firms such as Campari and Olivetti, which were among the first in Italy to create internal publicity offices. Olivetti’s Ufficio Sviluppo e Pubblicità (Development and Advertising Office), founded in 1931 and directed by Renato Zveteremich, functioned as a kind of laboratory. By hiring up-and-coming young designers – Studio Boggeri, Xanti Schawinsky, the architects Luigi Figini and Gino Pollini, and later, Marcello Nizzoli and Giovanni Pintori – it set the stage for the creation in the postwar period of the ‘Olivetti style’.

Munari and Ricas were among Olivetti’s earliest collaborators. The booklet 25 anni Olivetti [25 years of Olivetti], designed by them and art-directed by Zveteremich, featured innovations such as an album format, a double-page grid, photography and photomontages, slab-serif type and black rules, duotone printing, printing on cellophane and a spiral binding. (It was printed by Guido Modiano, a key figure in debates surrounding the renewal of Italian graphic arts.) In a similar vein, if more functionalist, is R+M’s catalogue for the model aeroplane company Movo, around 1937, which features a sensitive arrangement of text, photographs and drawings within a modular grid – an innovation brought to Italy by Modiano and Persico’s pioneering work at Casabella. [4]

Cover from the booklet 25 anni Olivetti, 1933. Spiral binding, printed by Guido Modiano. When Olivetti’s publicity office moved to Milan in 1932, Munari was among the first artists called upon by its art director, Renato Zveteremich. Renato Bazzani Zveteremich, Milano / Associazione Archivio Storico Olivetti, Ivrea.

Milanese design culture

Italy’s general backwardness largely excluded it from the Modernist aesthetic that was spreading across Europe in the 1920s. Only in the early 1930s did the New Typography cross the Alps southwards, along with Rationalist architecture and painterly abstraction. In Milan, these different strains of Modernity formed an original ‘design culture’ from which modern Italian graphic design was to emerge after 1945. Milan was at the centre of the ‘Modernist controversy’ that arose in the broader context of Gruppo 7’s attempt to validate Italian architecture as a Modern style suited to the regime’s ambitions. The campaign for Rational architecture preoccupied the specialist press, especially Casabella, but despite a few significant achievements, it was forced to compromise with the monumentalism spreading through Italy’s urban centres. 5 In Milan, the Triennale and the annual trade fairs did allow for close collaboration between architects and graphic artists, leading to important, if ephemeral, integrated projects such as the 1934 aeronautical exhibition at the Palazzo dell’Arte.

Throughout the 1930s a heated debate in the specialist press would pit the traditionalism of book typography – embodied by Raffaello Bertieri and his magazine Il Risorgimento grafico – against a rational, expressive renewal of the graphic arts, as seen in Campo grafico, the magazine founded in 1933 by a group of young printing technicians.

The year 1933 was an annus mirabilis for Italian design: in parallel with the debut of Campo grafico, Casabella radically changed format and layout; an exhibition of graphic works from the German Werkbund, curated by Paul Renner at the fifth Milan Triennale, met with great acclaim; and Antonio Boggeri opened his eponymous studio, a full service agency whose work tended from the outset towards the most advanced graphic production, favouring an eclectic typo / photographic language.

Relying on input from experienced designers such as Imre Reiner, Käthe Bernhardt, Xanti Schawinsky (who lived in Milan from the end of 1933 until 1936) and later Max Huber, Studio Boggeri soon attracted young Milanese recruits, including Ricas and Munari. It was through their intense collaboration with Boggeri that Ricas and Munari developed a more resolutely Modern approach. Logos, catalogues, brochures, adverts – heterogenous as they can be – demonstrated a minimalist formula, mostly image-based, but with playful subversion and graphic invention.

Magazines

The R+M partnership came to an end around 1937. Munari, now signing his work ‘pubblicità m’, began to focus on advertising for companies in advanced industrial sectors such as chemicals (Duco, Acna), textiles (SNIA Viscosa, Rhodiatoce), engineering (Lavorazione Leghe Leggere / Alluminio) and plastics (Montecatini). This move, probably encouraged by Zveteremich, now freelance, meant neglecting the more general commercial area – with the exception of periodicals. [6]

Illustrated magazines had become a dynamic sector in the hands of Milanese publishers such as Rizzoli and Mondadori. By January 1939 Munari had joined Mondadori, overseeing art direction of its new weeklies. While Modernist influences had by then been partly assimilated into mainstream graphic production, Munari’s position in the early 1940s seems to be based on a personal synthesis of Modernist vocabulary tempered by a more poetic, even anarchic, attitude.

Munari’s influence is visible in the covers and the design of the women’s weekly Grazia: he worked according to an intuitive layout, without preset typographic grids, giving himself a great deal of freedom in the combination of backgrounds and borders and the crop of photographs, often going back to plain illustrations.

Cover of Tempo 67, 1940, documenting the first year of the Second World War. Apart from minor differences, the magazine’s adherence to Life’s model is clear, though Tempo granted more space to political issues. Photography played a role in the striking covers, which week after week presented Italian readers with an ‘official’ account of the war’s progress. Biblioteca Comunale Centrale Palazzo Sormani, Milan.

Propaganda and information

The news weekly Tempo was launched in June 1939, on the eve of the war. It was Italy’s first full colour illustrated magazine: large-format, full bleed photographic cover, 60-odd pages divided into columns on politics, news, literature and art. Tempo was an immediate success, with several foreign editions selling up to one million copies a week. Photography was a key element in its formula, and its graphic layout, overseen by Munari, had a decidedly popular American bent, modelled as it was on Life.

As well as overseeing the art department (where contributors included Fulvio Bianconi and Carlo Dradi), in his four years in Mondadori’s editorial office Munari produced twenty or so original photo features, encompassing curiosities, jokes and topics of war propaganda. In 1944 these were collected in a volume as Fotocronache by Editoriale Domus – Munari had joined the publishing house as art director of its architecture magazine, also called Domus, after the closure of Tempo. [7]

Apart from its often striking covers, Tempo’s design was not innovative: the typeface Landi was its sole concession to Rational typography, and its graphic design lay somewhere between the eclectic and the popular. It nevertheless became a long-term success in Italian publishing (Mondadori used the same approach in 1950 for a new illustrated magazine, Epoca – once again overseen by Munari). One notable aspect of Tempo was its information graphics, such as maps, diagrams and plans that accompanied articles about the war fronts. This visual development – which may have been inspired by Signal, a propagandistic German fortnightly distributed in occupied countries – soon became one of the magazine’s more distinctive features. Munari would perfect these skills further at Domus in 1943-44.

Postwar polemicist

During the war years, in addition to art direction for Mondadori and Editoriale Domus, Munari designed book jackets for Bompiani. This early entry into the cultural industry anticipated later consolidations in the Italian graphic arts. Whereas in the 1940s Olivetti was practically the only instance, the 1950s saw important synergies between intellectuals and technologically advanced industrial firms such as Pirelli, Italsider, Rinascente, Montecatini, Rai and Roche. After the war Munari would re-emerge not only as an artist and graphic designer but also as industrial designer and pedagogue. Despite his previous acceptance of the Fascist climate, Munari’s work and activities throughout the postwar period were informed by a progressive outlook. First with the Movimento Arte Concreta (Concrete Art Movement), and later through his writings and his teaching, he became a spokesman for the designer’s social role.

‘Today, the artist must step off his pedestal and deign to design [even] the butcher-shop sign (if he knows how) [… and] become an active person amongst others, aware of current techniques, materials, and working methods, and – without abandoning his innate aesthetic sense – humbly and competently answer the questions one might pose. The designer is now the point of contact … between art and the public … It’s no longer the painting for one’s living room but rather the kitchen appliance. Art mustn’t be separated from life: [with] beautiful things to be looked at and ugly things to be used.’ [8]

Notwithstanding a number of highly original visual investigations (the award-winning ‘illegible [wordless] books’, which eschew textual communication for aesthetics; light projections; experimental films; fountains; toys; and teaching workshops) and his book design, which helped define the identity of publishers such as Einaudi, Bompiani, Rizzoli and Editori Riuniti – establishing his own place in the Italian design scene would be increasingly problematic for Munari.

By the late 1950s Munari seemed constricted by an outdated Modernist formula that was pictorial in character rather than typographically structured.

Though this approach was well suited to the children’s books and toys he created, it may have hampered his wider success as a graphic designer. Yet his commitment to the world of childhood and education, culminating in the creative workshops for children he established in the late 1970s, allowed him widespread, popular recognition that few other Milanese designers have attained.

Footnotes

1. Munari quoted in Andrea Branzi, ‘Il gioco del fare. Intervista con Bruno Munari’ in Modo 8: 71–72 (August–September 1984): 42.

2. No surviving copies or photographic extracts are yet known.

3. Munari may have seen Bayer’s work in die neue linie, a women’s magazine, art-directed by Moholy-Nagy and Bayer.

4. Designer, printer and critic Guido Modiano (1899–1943) specialised in prestigious editions and cultural periodicals such as Quadrante, Edilizia Moderna and Le vie d’Italia. Alongside Edoardo Persico, he played a major role in the redesign of Casabella’s graphic look.

5. After Florence’s Santa Maria Novella station, other notable examples of Modernist Italian architecture include Terragni’s Casa del Fascio (Como), Pagano’s Università Bocconi (Milan), and the Città universitaria and Termini station (Rome).

6. Renato Zveteremich left Olivetti in 1938 to work as a freelance consultant for industrial conglomerates such as Montecatini, Schering and Farmitalia.

7. Tempo closed following the German occupation of northern Italy in September 1943.

8. Bruno Munari, Arte come mestiere [Design as Art] (Bari / Rome: Laterza, 1966).

Cover of La Lettura XXXVII 7, 1937. The illustration was created with a ‘tactile’ technique, using a three-dimensional assemblage of cut-out photographs, cardstock, fabric, and sandpaper. Biblioteca Nazionale Braidense, Milan.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue. You can see what Eye 85 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.