Summer 1991

Mondo magazines

Some of the sharpest and most influential graphic design ideas come from the new magazines. Eye thumbs the pages of the international press and takes a close look at three of the most consistently creative titles: i-D, Interview, and Beach Culture

‘Magazines today are timid. They have no self-confidence.’

‘I think that art directors today have too much impact … Editors are relying on design to sell lame ideas.’

‘I feel like an old fuddy-duddy talking this way, but nevertheless, there were once basic aesthetic standards for magazine design that do not exist today.’

These remarks were made by the late Cipe Pineles, Sam Antupit and Will Hopkins at a symposium organised by the American Institute of Graphic Arts in 1985. The ‘golden age’ of mid-century American design was long over – a victim of television, the 1970s recession, editorial caution and the publishing houses’ loss of nerve – and the self-confident generalist magazine appeared to be in terminal decline. It was hardly surprising that the golden-agers should yearn for the days when the editorial well was sacrosanct and the covers provided a monthly canvas for their surrealistic rebus pictures. But if they were looking for evidence of revival at their old companies – at Hearst and Condé Nast – they were certainly looking in the wrong place. For even as they voiced their misgivings it was becoming apparent that magazine design was not in fact dying at all. It was flourishing in a different area – in the small-scale publications which were the primary forum for the youth culture interests of music, fashion, art and sport.

In the 1980s, at least four magazines developed a vision of editorial content and design sufficiently cohesive to justify the description ‘great’: The Face, i-D, Spy and the Italian edition of Vogue (of which only the last came from an established publishing house). At the same time, culture tabloids such as Fetish, Hard Werken and Emigre helped to introduce a much freer typographic mentality. The decade saw the revival of the mens’ general interest / fashion magazine: Arena in the UK, Edge, X-Men and the exquisite Piacere Rakan in Japan, Globe in France, and El Europeo in Spain. There were some bright new pictorial / feature magazines dedicated to reporting the dark, the bizarre and eccentric: Actuel in France, Tempo and Wiener in Germany, and King in Italy. The last of these, designed by Studio Sergio Sartori, was the most selfconsiously decorative. With its ornate headlines and patterned borders, King was an abrasive European example of the ostentatious post-modern styling that dominated American magazines such as Esquire, Metropolitan Home and Egg.

But these were yuppie successes: what of the increasingly austere 1990s? With the publishing industry once again in crisis, this might seem a perverse moment to celebrate magazine design. The UK and US are in recession, and in Europe and Japan growth has come to a stop (in 1990, for the first time in six years, the number of new launches in the US fell to only 536). Meanwhile, advertising revenues are plummeting, editorial budgets have been cut and paper formats have shrunk. Already the designers’ magazine of 1991, Beach Culture has in only its sixth issue been reduced in size.

The result is that at the major publishing houses there is once again a moratorium on creativity. Where they cannot produce new publishing ideas, corporate publishers buy into formerly independent titles such as Details and Arena. Where there is a ‘new’ idea, it manifests itself in second-rate products such as Allure (US) or the British version of Mirabella. Allure, the ‘beauty’ magazine from Condé Nast, has an editorial and design format that appears to have been cobbled together from Looks, Actuel, Best and Prima, creating a typographic pick-and-mix of ornate serifs, gothic and typewriter faces. Mirabella has already folded, an unmourned victim of the recession. But the situation as a whole is far from depressing. A glance above or below the newsstands’ prime-site shelf space reveals a wealth of imaginative magazine design created by individuals rather than committees, editors and designers rather than advertising executives and marketing departments. There are many independent publications in the fields of art, music and sport which continue to exploit the ephemeral qualities of the magazine medium to create adventurous, experimental design.

Few designers, thankfully, are listening to such critics as Joseph Giovannini, who claims in an essay against current magazine design practice that ‘The style and aesthetics of a page are surreptitiously usurping the meaning traditionally posited in words and images.’ According to Giovanni, magazine design ‘is simply a way to structure and clarify content’, but this is a much too simplistic a view of magazines as a medium. At its best, magazine design not only orders and amplifies editorial ideas, but creates them in a considered fusion of image and text.

It is already clear that different ideas about structure and style are emerging, driven by technology and by the intellectual and economic climate. Desktop publishing systems have changed not only the design of magazines, but also their economics, enabling small-circulation titles like Wire and Straight No Chaser (both about jazz) to thrive because production costs have fallen so low. Magazines like Road, Lime Lizard, Beach Culture and i-D (not new but still ahead of its time) typify the new approach to magazine design and publishing which has evolved from increased editorial specialisation.

A fondness for the oblique over the direct, for the artful reference rather than the obvious graphic pun is typical of the new magazines. Few designers are as wilful and extreme as David Carson, art director of Beach Culture, but intuition is generally preferred to the rationalism of the golden age. Typography is given rounded, biomorphic shapes, partly inspired by the revival of interest in the 1960s, partly a measure of the influence of popular culture on self-conscious, educated graphic design. Type is used semantically and figuratively as an expression of content: this is particularly evident in Tibor Kalman’s designs for Interview and in Stephen Male’s work for i-D.

Page structures, too, are built with great fluidity, with radical departures from the sequential three-column grid and the pyramidal hierarchy of type. The parallel page structures used by Rudy VanderLans at Emigre are finding their way into commercial publications. Lime Lizard, a British music magazine designed by Kevin Grady, takes the reader along a complex mesh of columns. At Wire in the late 1980s, Paul Elliman’s refined typographic constructions contracted headline and standfirst into a single block of type, or two interlocking panels reading in parallel. These are journalistic approaches and sophisticated methods of leading the reader into an article. In a newspaper, the function is traditionally handled by the banner headline and magazines have tended to follow suit. The new magazine designers are showing that it is possible to create more subtle transitions and linkages between image, headline and story.

These aspects of the new magazines are, in general, in keeping with trends apparent in other printed media. Where magazine work differs is in the time allowed relative to the amount of design required. Magazine art directors, as a result, are less concerned with finish than with shouting out the message, and this is the great strength of the medium. The magazine business continues to exist on the edge of mainstream design – much is self-taught, there are fewer academic restraints, less concern with the superficial (sometimes, at least) and a greater openness to popular culture. This is a very good recipe for progress and invention.

Interview

Tibor Kalman’s art direction of Interview is a measure of the degree to which the designer with wit can become an active participant in the editorial process, creating a visual journalism which not only projects, but also determines the content of the magazine. This process includes both the ‘packaging’ of otherwise routine editorial material and the production of thematic issues in which text and image are united in formal and conceptual execution. In Interview, the personality of the interviewee is expressed – critically – in the construction of pull quotes and opening spread, while visual unity is achieved by constantly repeating the shape of images in concrete typographic form. The carefully considered commentary provided by the design is achieved with a minimum of typographic variation, the maxim being that it’s not the typeface you use – it’s the way that you use it. Nevertheless, there are similarities between Kalman’s literary approach to editorial design and that of his predecessor, Fabien Baron. Both adopted a certain theatricality played out within a sparing design system. But where Kalman attacks the reader primarily with language, Baron treated headline letterforms as an opportunity for abstract type constructions. Every article was developed as a succession of glamorous visual dramas, and was divided with extreme formalism into headline, stand-first and text spreads. The beautiful simplicity which Baron had developed in the Italian edition of Vogue was well suited to Interview’s commissioned art features, and also provided the magazine with a powerful thematic glue.

i-D

i-D has always prided itself on staying one step ahead of its readers and this attitude extends to its design. ‘To know what’s right now you need to know what was right last week,’ says Stephen Male, art editor / director since 1987. While The Face, after Brody, experienced a long spiral of decline in editorial conception and graphic impact, i-D has recreated itself with utmost unprecedented regularity, to become one of the most accomplished magazines of the last ten years. Page sizes and formats have varied and the magazine’s treatment of typography, photography and page layout – based on the try-anything ‘instant design’ aesthetic of its founder, first designer and editor in chief Terry Jones – has mutated in accordance with its apprehension of the prevailing mood. Throughout the acid house party / Ecstasy era, i-D’s identity was dominated by colour-saturated trash graphics and a set of typefaces, such as Eurostyle, that had not seen reputable service for years, if ever. Its current shattered-typewriter look is monochromatic and austere, restoring a sense of flatness to the page and reality to the reader. i-D’s design strength stems from its conceptual clarity. Editorially, the magazine has never abandoned its initial desire to document the mores and styles of youth culture, whatever form they might take. Far from acting as constraints, simple ideas like the use of the winking cover-girl and the insistence on an issue theme (‘The life and soul of an issue’, ‘The dangerous issue’) have created a framework for creativity, while ensuring a consistent identity, whatever innovations the magazine’s designers attempt.

Beach Culture

Beach Culture, designed by David Carson, documents the lifestyle and outlook of a precise demographic group located culturally across America, rather than geographically along a strip of coastline. To judge by its letters page, its biggest readership would appear to be in the Midwest, 1500 miles from the nearest wave. Knowing that it isn’t so much the subject matter that counts as the editorial attitude, the magazine’s content skitters erratically between avant-garde art and surfing. What matters above all is the intimacy of the relationship between the title and its readers; the confidence that this closeness engenders allows Beach Culture’s editor and designer to take risks and leader their audience into new and uncharted territory. Carson has largely dispensed with page numbers, the contents page is indecipherable and headlines are dismembered with deconstructive abandon. Such an approach would be commercial suicide outside the narrow subculture enclave inhibited by Beach Culture and similarly intentioned magazines, but to Carson’s readers impenetrability would seem to be a source of satisfaction: presumably because it helps to keep outsiders out. Sceptics say the magazine has been rendered unreadable because it wasn’t worth reading in the first place, but is this a matter for the designer to decide? Beach Culture demands a critical response because it applies typographic ideas more familiar from Cranbrook Academy of Art student projects with a limited circulation to an internationally distributed magazine. Carson achieves a kind of scrambled coherence, but Beach Culture’s legacy is unlikely to be positive, as its mannerisms are copied and applied in situations where they clearly do not belong.

William Owen, design writer, London

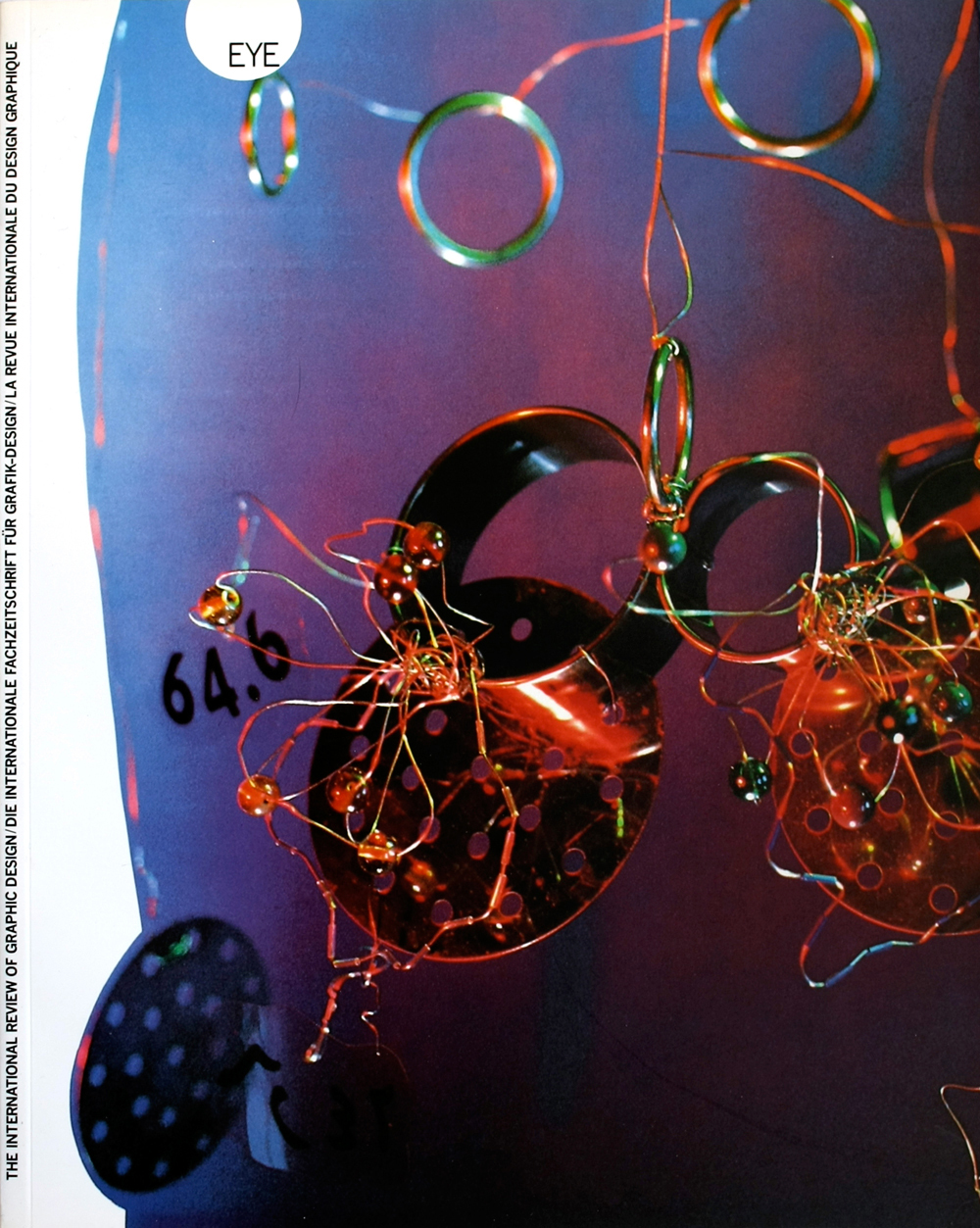

First published in Eye no. 4 vol. 1 in 1991.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.