Summer 2004

Mystery and clarity

These children’s book illustrations captured moments of social history

A touring exhibition of the work of John Berry and Martin Aitchison, who produced illustrations for the Ladybird series of learn-to-read books in the 1960s and early 1970s, has excited a nostalgic reappraisal of these two octogenarian artists. A generation of British children was weaned on their work and Ladybird books from this era enjoy an unrivalled cachet among many designers and illustrators.

It’s not hard to see why. These books are beautiful objects: typographically sophisticated and bristling with a laudable social and pedagogical intent. They were conceived by writer and teacher William Murray as a tool for the promotion of literacy. A note to teachers and parents spelt out their purpose: ‘The full-colour illustrations have been designed to create a desirable attitude towards learning – by making every child eager to read each title. Thus, this attractive reading scheme embraces not only the latest findings in word frequency, but also the natural interests and activities of happy children.’

For anyone who grew up in Britain in the 1960s or early 70s, the appeal of Berry and Aitchison’s work may be principally nostalgic. But even for those born later, the duo’s work captures a widely recognisable moment in recent history: the transformation of Britain from a dowdy, war-ravaged country into an affluent, technologically enabled modern state. In 1964, the then Prime Minister Harold Wilson famously spoke about a new Britain forged in ‘the white heat of technology’: Berry and Aitchison recorded this transformation in their Ladybird illustrations. The studied realism of their paintings, especially Berry’s frequent depictions of the nascent technological revolution, was a departure from the earlier patriarchal and often saccharine tone of children’s book illustration. Berry and Aitchison depicted a nation on the cusp of profound cultural change: a nation about to get modern. They were the Norman Rockwells of 1960s Britain: for sizzling turkeys and home-made apple pies, substitute automated car factories and police cars next to high-rise blocks; for mawkish over-romanticising, substitute emotional detachment. The writer Michael Bracewell sees comparisons with more modern figures, such as photographer Martin Parr.

John Berry studied at the Royal Academy School of Arts in the 1930s and has a distinguished career as a society portrait painter. He painted Lady Astor; the young Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip; Diana, Princess of Wales; and George W. Bush. But he also worked in advertising, and this manifests itself in his Ladybird illustrations. It is said that Berry ‘could do anything, provided he had a photograph to work from.’ You can see this in his sparsely elegant portrait of a railway worker: the man dominates the frame in a way that is clearly influenced by commercial photography. He has the demeanour of an airline pilot, and in his Cardin-style uniform, he cuts a strikingly modern figure. Behind him we catch a flash-frame of contemporary railway architecture; it is new and sharp, and has doubtlessly replaced a piece of crumbling Victoriana.

Berry’s paintings look like an advertising campaign for Harold Wilson’s new Britain. There’s nothing messy or distracting in his world; everything is hygeinic and clean. To present-day eyes, accustomed to the advertiser‘s view of a sanitised and wart-free world, it is a surprisingly modern vision.

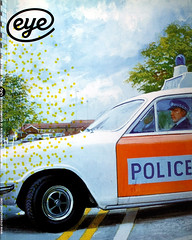

But Berry stops short of ad-land spin: he always retains an element of Anglo Saxon restraint; his skies are an optimistic blue, but they are not cloudless, they have a familiar grey-tinged turbulence that renders them authentic. His painting of two policemen in a car is like a still from a new-realism British TV cop show of the time. These are modern policemen, not the friendly ‘bobbies’ traditionally encountered in children’s literature. They are anonymous bureaucrats keeping order in a modern metropolis. A tall building, an office block, looms over them. It is white and clean and surrounded by strategically planted trees. Berry’s best work records the rise of a new Britain created by town planners and urban developers. Another painting is an eerie depiction of a car descending into an underground car park: no human beings are present and the car appears driverless. It is an almost Ballardian view of modernity, reminding one of Paul Valéry’s remark that nothing is as mysterious as clarity.

By contrast, Martin Aitchison’s work is less technologically focused. It is cosier, more humanistic, but no less revealing in the way it captures the rhetoric of life in 1960s Britain. Aitchison studied in Birmingham and at the Slade in London. He planned to become a painter, but as he noted in a recent interview, ‘After the war, my attitude changed and I began illustration and advertising as a freelancer.’ He was employed by the publishers Hulton as a contributor to the children’s comic The Eagle, where he illustrated ’Luck of the Legion’.

Aitchison shares Berry’s visual immediacy, but their styles are different. You can see it in their handling of policemen. In Berry’s hands they are shadowy robocops, while under Aitchison’s gentler scrutiny, they become benign public servants anxious to please. In one of Aitchison’s scenes a youngish ‘copper’ instructs an attentive girl in road safety. Behind him another policemen bundles a drunk into the local police station, while others go calmly about their civic business. In another painting, a friendly motorcycle cop, with leather gloves and an implausibly neat uniform, talks to two children. They are by the seaside, and the impression is of a scene from a children’s adventure story. Compared to Berry’s techno Britain, Aitchison’s Britain is still cloaked in the prewar hegemony of traditional patriarchal values.

Aitchison worked from real models rather than photographs. It shows in his two portraits of children investigating family heirlooms. The first of the two paintings was done in the mid-1960s, the second in the early 1970s. Some changes have taken place in that short period. In the earlier scene, the children are dressed in the clothes of an earlier time. They look like children from the 1945 film Brief Encounter: the girl is dressed in a frock; the boy in the middle-class uniform of shorts, white ankle socks and T-bar sandals. But by 1972, when the second picture was painted, both children are dressed in casual attire of dungarees and trainers.

Looking at John Berry and Martin Aitchison’s work 30 or 40 years after it was first published, we see the beginnings of political correctness, mild attempts at social engineering, and a new honesty and realism in the images presented to children. But we also see history. As increasingly we become a society of the visual, and because we have come to mistrust the authoritarian lessons of history, we turn to the footprints of popular culture and mass imagery for our understanding of an earlier world. Berry and Aitchison’s Ladybird work seems as effective as photography, television programmes, films and historical texts in its depiction and illumination of a period in our recent past. In some ways, it is more illuminating because it deals with life, work, play and childhood in a realistic and largely unpatronising manner. Their work allows a generation to interpret its collective past.

Adrian Shaughnessy, writer, creative director, London

First published in Eye no. 52 vol. 13 2004

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue.