Autumn 2009

Not all black and white

Alfred Martin Duggan-Cronin

Ernest Cole

David Goldblatt

Pieter Hugo

Jo Ractliffe

Guy Tillim

Mikhael Subotzky

Zander Blom

Changes in South African photobooks reveal a nation now free to explore its self-image

The African independence struggles of the past century, which culminated in South Africa’s transition to a nonracial democracy in 1994, were waged over more than territorial space: other, intangible things were at stake, too. Independence allowed Africans to claim autonomy over their self-image, something long catalogued, quantified and archived by generations of visiting (mostly white) photographers. The history of the South African photobook is in part a record of how this quest for self-image manifested itself in bound form.

‘What makes it difficult for any South African artist with a genuinely creative ability to express himself in this country is the fact that the significance of the African continent has met with so little understanding,’ remarked the short story writer Herman Charles Bosman – whose Faulknerian sense of place would greatly influence the photographer David Goldblatt – in 1942. For Bosman this was because the wrong people were speaking on behalf of the continent; for him the villains were the economist, archeologist, historian, man of religion and ethnologist. ‘It is for the poet and the artist to tell us about the real Africa,’ he declared.

‘The situation in which the South African writer finds himself is quite simply out of this world,’ countered the Nigerian Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka in his 1967 essay, ‘The Writer in an African State’. For any South African writer – and, by extension, photographer – to linger on ‘magic’ and ‘the blossomings of witchery’, as Bosman had done in his writings on African art, was to wish away what Soyinka concisely described as the ‘bleak immensity’ of the apartheid condition.

Child minder in Joubert Park, Johannesburg, 1975, from David Goldblatt’s Particulars (2003).

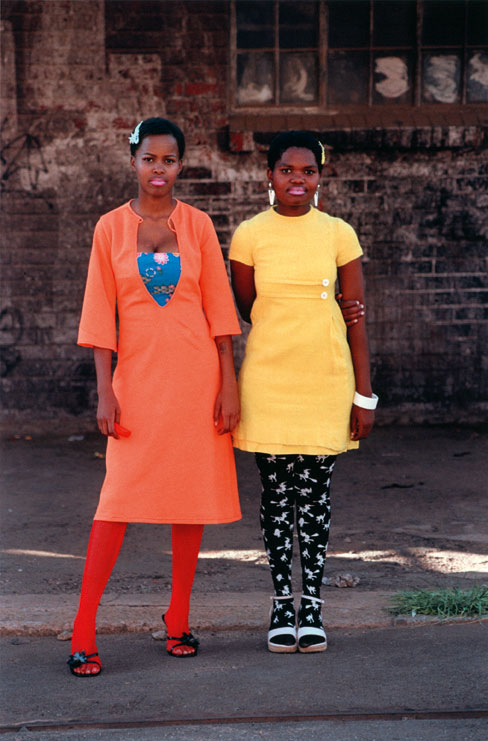

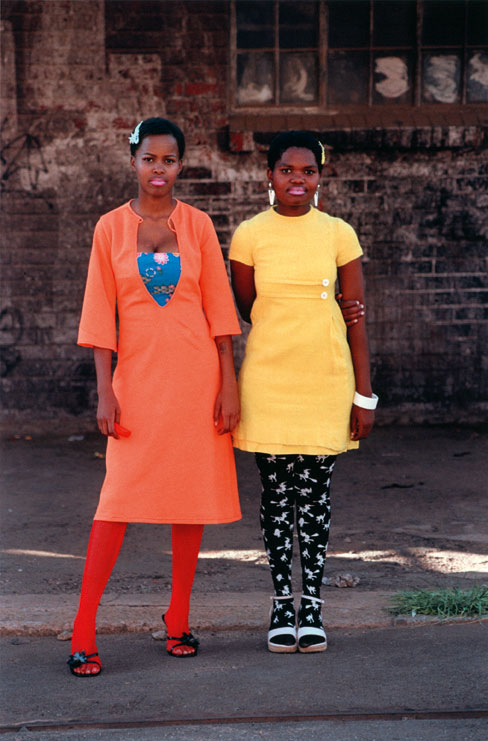

Top: Cindy and Nkuli pose for Notsikelelo Lolo Veleko’s camera, from her ‘Beauty is in the eye of the beholder series. Wonderland presents her street portraiture alongside cryptic documentary snapshots of urban scenes and flora.

This bleakness is absent from one of South Africa’s foundational photobooks, Alfred Martin Duggan-Cronin’s eleven-section, four-volume publication, The Bantu Tribes of South Africa (Deighton, Bell & Co / MacGregor Memorial Museum, 1928-54). Like Roger Ballen many decades later, Duggan-Cronin was an expatriate (an Irishman), his career in photography prefaced by a stint working in the mining industry as a compound guard in Kimberley. Duggan-Cronin acquired his first camera in 1904, at age 30. Fifteen years later, with backing from Kimberley’s McGregor Museum and the Carnegie Institute, he began work on an ambitious project to document the indigenous population of southern Africa. The project kept him busy for 25 years and yielded about 6000 photographs, many of them portraits.

At face value, Duggan-Cronin’s project shares some obvious affinities with August Sander’s mammoth undertaking to index the German population. Duggan-Cronin, however, was not recording his own people. The ethnographic undertow is clear in the design treatment: each photograph is presented at right, the photographic plates separated by semi-transparent captioned interleaves. ‘Zulu Woman’, reads one label, the vague outline of the sitter visible underneath. A brief annotation further illuminates the hazy picture, to which one eventually turns: ‘Note the strings of beads which she uses as ear-rings, also the necklace of charms.’

Although Duggan-Cronin was a skilled portraitist, clearly respectful of his subject, the outcome is a publication that, in the words of art historian John Peffer, is equal parts ‘factual document and paternalistic fantasy’ – a naturalistic study of an unnatural situation. Ernest Cole, South Africa’s first black freelance photojournalist, made it his mission to expose the lie. A visual journey through the multiple degradations of high apartheid, Cole’s House of Bondage (Random House), published in the US in 1967, is an important book, recording in pictures what the author describes in his introduction as the ‘extraordinary experience to live as though life were a punishment for being black’. Drawing on his experiences as a layout artist at Drum, a magazine in the mould of Life or Picture Post, Cole’s book functions as series of thematic photo essays. His photographs are assiduously captioned, some juxtaposed for fuller effect.

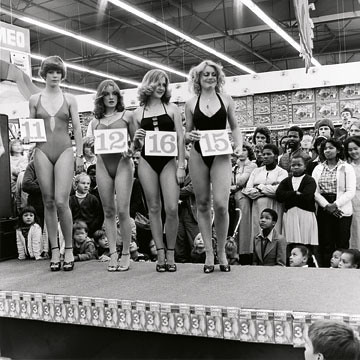

Contestants in the Miss Lovely Legs Competition at the Boksburg Hypermarket, circa 1979-80, from Goldblatt’s 1982 book, In Boksburg.

Perhaps the most striking (and startling) aspect of the book’s configuration is the opening essay, which shows ‘pensive tribesmen’ in threadbare contemporary fashion being assimilated into the country’s mining system. A full-bleed image of these young men stood naked, hands in the air, ready for a medical inspection, is a damning riposte to Duggan-Cronin, and his many lesser copyists.

Although banned from circulation in South Africa, House of Bondage is the obvious precursor to such bleak, unsentimental books as Peter Magubane’s Soweto (Don Nelson, 1978), Omar Badsha’s Letter to Farzanah (Institute for Black Research, 1979), Paul Alberts’ The Borders of Apartheid (The Gallery Press, 1983) and Goldblatt’s Lifetimes: Under Apartheid (Jonathan Cape, 1986), a collaboration with author Nadine Gordimer.

Goldblatt, a photographer whose imprint on contemporary South African photography is as pervasive as it is profound, also collaborated with Gordimer on his first book, On the Mines (Struik, 1973). The book, a somewhat disconnected series of landscape studies, portraits and action photographs, reveals the design influence of Sam Haskins, a photographer from Kroonstad, south of Johannesburg, who had a studio in London in the late 1960s (he is now based in Australia). A graphic innovator, Haskins came to prominence with the publication Cowboy Kate and Other Stories (Bodley Head, 1964), a collection of grainy, juxtaposed glamour portraits that defined the permissive character of 1960s lifestyle photography. ‘The layout, sequencing and overall graphic look is the book,’ offers designer Garth Walker. ‘The photos are a means to get there.’

After a false start working with Haskins on a book of pictures of Afrikaners for possible international publication, Goldblatt settled on a strategy that confined the design entirely to double-page spreads, with the photograph on the right-hand side, and the caption on the left. ‘Keeping the captions close to the pictures was a vital aspect of the design, while sequencing was the principal tool for making what I hoped was a sort of musical score,’ he said.

Experiments in design

On the Mines, despite the lingering influence of Haskins in the grainy impressionist landscape studies rendered full-bleed at front, confidently announced Goldblatt’s austere vision, born of a deep empathy for his subjects. Some Afrikaners Photographed (Struik, 1975), initially intended as his first book, followed two years later. It is however the photographer’s fourth book, In Boksburg, an extended essay on a small mining town on the eastern periphery of Johannesburg that stands as the culmination of youthful doggedness and a fully achieved maturity.

Mikhael Subotzky’s Beaufort West (2008) includes images of life in this remote town’s prison, located on a central traffic island.

Independently published by photographer Paul Alberts, In Boksburg (The Gallery Press, 1982) ennobles the particular without lapsing into formalism or hectoring politics. By comparison, Peter Magubane’s Soweto, an undeniably valuable historical record, merely applies Cole’s template to a defined, highly emblematic space, without much differentiation photographically or graphically. In Boksburg, with its fastidiously quiet design, curtailed focus and acute awareness of the political context framing the pictures, has been hailed ‘a classic example of his subtle method’ by Martin Parr and Gerry Badger in their two-volume history, The Photobook.

If Goldblatt established the benchmark for photography concerned with specificity and place, American-born Roger Ballen has pioneered the converse, his photography a journey to a placeless psychological realm.

It wasn’t always that way. Ballen’s second book, Dorps: The Small Towns of Africa (Clifton Publications, 1986), is a diffuse, nostalgic record of rural South Africa – its people, its architecture, its decline. As with all Ballen’s books, Dorps is marked by an unobtrusive, classical approach to photobook design. Everything is calculated to guide you to the pictures, to ‘Roger’s world’, as Ballen nowadays describes the photographic spaces he evokes. His latest book, Boarding House (Phaidon, 2009), is a compendium of claustrophobic tableaux that fictionalise elements of his past photography, shifting the emphasis from fact to artefact. Johannesburg photography dealer Gavin Rooke describes it as ‘a vehicle to host the images and tell a more encompassing story’.

Of the younger generation, Guy Tillim, heir apparent to Goldblatt, is one of the few contemporary photographers to experiment with photobook design, often with mixed outcomes. His debut book, Departure (Bell-Roberts, 2003), is a conventional package; Jo’burg (Filigranes Editions / STE, 2005), winner of the 2005 Leica Oskar Barnack Award, marks the real departure. Taking as its subject the cramped, substandard living conditions of Johannesburg’s inner-city poor – vertical township dwellers – Tillim presents his gritty yet allusive photographs across a single concertina-folded length of paper. Though not entirely successful as a graphic solution, it prompts unexpected juxtapositions.

Petros Village (Punctum, 2006), an unconventional essay on a rural Malawi village, follows the same treatment, while Congo Democratic (Galleria Extraspazio, 2006), an essay on electioneering in the Democratic Republic of Congo, is better described as a large-format portfolio than a photobook.

In the wake of South Africa’s reintegration into Africa, many photographers have opted to venture north, in search of images and connection. Tillim’s most recent book, Avenue Patrice Lumumba (Prestel, 2008), is an expansive, open-ended project documenting the post-colonial architecture of Mozambique, DR Congo, Madagascar, Angola and Benin; it also marks his return to the more stable architecture of a conventionally bound book of single images.

For her book Terreno Ocupado (Warren Siebrits, 2008), Jo Ractliffe travelled to the Angolan capital of Luanda, ostensibly in search of lost dogs. Intrigued by Ryszard Kapuscinski’s account of animals ‘abandoned by owners fleeing in panic’ in Another Day of Life (1988), a recollection of Luanda’s fraught transition to postcolonial rule in 1975, Ractliffe decided to go find the dogs.

Fantasy and role-playing

Where Ractliffe’s photography eschews documentary literalism, her photographs an attempt to record things ‘beyond the appearances and documentary state of things’, Pieter Hugo’s photographs of travelling mendicants with their hyenas, honey collectors, taxi washers, people with albinism, actors and the recently dead enact a not entirely unfamiliar fantasy. Like Duggan-Cronin, Hugo, whose style was influenced by his time as an editorial photographer with the magazine Colors, has built up an impressive archive of ethically ambiguous portraits. Like Ballen, who was heavily criticised for his portraits of poor whites in the book Platteland (St Martins Press, 1994), Hugo has shifted his practice into realms of fantasy and role-playing, this after a less than successful detour into the documentary essay, Messina / Musina (Punctum, 2007), a graphically impressive but photographically disappointing study of life in South Africa’s northernmost town.

Matthews Ngwenya and a friend sleep in the winter sun on the roof of Sherwood Heights, from Guy Tillim’s book Jo’burg (2005). Sherwood, like many other buildings in the centre left abandoned by a large-scale exodus of whites from the city centre in the 1980s and 90s, has been earmarked for low-cost housing.

Directly influenced by and sometimes even quoting Goldblatt’s In Boksburg, Mikhael Subotzky’s Beaufort West (Chris Boot, 2008) – awarded the 2009 Leica Oskar Barnack award – is a more thoroughgoing statement on South Africa’s difficult transition, also offering a rural outpost as national emblem.

Born in 1977 and four years older than Subotzky, former graphic design student Nontsikelelo ‘Lolo’ Veleko offers a counterpoint to the young Magnum nominee’s stern vision. Although hailed as a successor to the great West African studio tradition of Seydou Keita and Malick Sidibe for her eye-tingling, fashion-infused street photography, Veleko, who comes from a mixed-race family, actually came to the format via Japanese photographer Shoichi Aoki, founder of the cult street fashion magazine Fruits. Her debut book, Wonderland (Self, 2008), is an entirely partial and optimistic record of youth. The formal grid and playfully restrained type treatment recall early i-D, a magazine conceived at a time of multicultural encounter.

Another young notable is Zander Blom, whose eccentrically brilliant Drain in Progress (Rooke Gallery, 2007) offers an anxiously playful engagement with the legacy of European Modernism. Blom, with his predilection for photographing the unusual stage sets he constructs in his home, captures something of the Zeitgeist of a younger generation of photographers free to define themselves as they please in a post-apartheid context.

‘For a long time I aspired to make the kind of immaculately crafted work in media that would last forever,’ Blom writes in Drain of Progress. ‘When I killed that ambition a big weight was lifted off my shoulders.’ Of course, his lavish photobook was designed to last a very long time.

First published in Eye no. 73 vol. 19 2009

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue.