Spring 1992

One from the heart

Four years ago, Rick Valicenti said goodbye to his corporate clients and set out to reinvent himself. Now his company, Thirst, makes art with a function.

For a man who plays with myths, working from a studio on a street with no name in a Chicago neighbourhood far from the glamorous postcard image of the windy city can be no accident. In early 1988, Rick Valicenti launched Thirst, or 3st, depending on how playful you like to treat the written word, making a deliberate decision to reinvent himself as a pioneering free spirit.

If imitation is anything to go by, Thirst are most definitely flavour of the month on the US graphic design scene. Recent accolades include supplying ten of the 99 entries published in the 1991 American Center for Design 100 Show catalogue. Valicenti also caused a stir at the 1991 American Institute of Graphic Arts conference, where an audience of 1,500 received individual copies of a self-promotional montage showing typical approaches.

Valicenti uses much of the same vocabulary as the currently modish deconstructivist school to create a journey of discovery for the viewer, through layers of text and imagery, towards the sometimes elusive goal of meaning. Less overtly intellectual and lighter in his touch than the theorists at Cranbrook Academy of Art, he has created a populist version of an ism that some commentators have dismissed as a device adopted by élitist designers simply to browbeat and baffle their audience.

The debate surrounding Valicenti hinges on whether his professional gear change is a clever marketing strategy or comes straight from the heart. Sitting cross-legged in front of a cinema screen showing slides of recent work and Thirst’s first attempt at video, the latest American design star urged to fellow members of the AIGA to question what they do and demand that clients respect their integrity. Baring his soul and even shedding the occasional tear, he split the sympathies of his audience down the middle. ‘My livelihood is based on reputation alone and that comes from the design community buzz,’ he confessed later, ‘So I knew the consequences if I made myself look foolish.’ Valicenti had put himself squarely on the line and was inclined to think that the gamble had paid off.

The Road to Damascus experience that transformed R. Valicenti Design into Thirst came when Valicenti realised that as principal of his own design firm he had become little more than account executive. The reconstruction has been radical. Valicenti now gives away stickers with portraits of old, corporate, besuited version of himself, signed ‘Love Rick xo’. The majority of his clients were large Chicago financial institutions. ‘They knew the formula needed to market their products. But quite often they would develop new products and use old formulas and I would be held accountable. They would praise or blame the design styling and I was tired of just being the stylist – it came to look like cake decoration.’ So Valicenti raised his hand, ‘spoke out of turn and asked to be invited to the meeting’. A mutual sacking between the designer and all but one of his clients ensued.

The personal philosophy defined by this conflict is based on Valicenti’s belief in the power of graphic design, while the key to his working methods lies in his education. As a student of fine art and photography he was taught to express himself. ‘That knowledge means that you can express someone else’s interest,’ insists Valicenti. ‘When you translate honest intent you capture all the idiosyncrasies and emotions of what the client is really about.’ Now Thirst follow three essential commandments: first, acknowledge the process of design; second, accept that the business is about creating versions of reality; and third, make self-expression evident in every job. The result, Valicenti claims, is ‘art with function’.

Valicenti, like other deconstructivists, likes to write his own words to fit, but about half the copy he plays with is supplied by Chicago copywriter Todd Lief. Together they come up with cute and witty word constructions that dare readers to let go and free associate their way through streams of letters, numbers and symbols much as a child readers, unhindered by conventions of grammar and logic. Even Valicenti’s letters are signed off ‘Ciao 4 Niao’. With the aid of the Macintosh, copy can be inverted or over-printed, condensed or stretched until it is almost illegible. A current project, which teams up theorists and designers to co-produce essays for a volume entitled Semiotext(e)/Architecture, contains spreads that ignore the gutter, as well as pages of type so closely leaded that it overlaps, thwarting the efforts of even the most conscientious reader.

Naturally enough, Valicenti can explain every element of a particular spread, pointing out hidden messages and the inevitable jokes. The stumbling block is that most viewers do not have the designer standing next to them clarifying his intentions. For the method to work, viewers must engage with the design as closely as they would with a novel or film. Two recent commissions, large double-sized posters announcing the opening of a lighting showroom, also function as commentaries on the language of graphic communication. By aping and undermining advertising conventions, they demonstrate how well trained we are at responding to the hidden persuaders that say ‘buy’.

What makes each solution unique is Valicenti’s skillful, if sometimes glib, manipulation of language and the wide range of ‘voices’ this gives him. The finished designs, in an impressive range of graphic styles and media, bombard both eye and ear. This is not simply a smoothly practised plagiarist at work. ‘I want to say that it’s okay to go the same cupboard that Paul Rand went to because you can relate to that recipe for success – success being not the pay cheque, but the emotion you experience from something by a master like Rand. You spend your whole life trying to regain that feeling from your own work.’ Valicenti draws a verbal diagram of shock waves fired off by El Lissitzky and reverberating along a chain of activists, including Cassandre and Schwitters in Europe, Neville Brody in England and himself in the US.

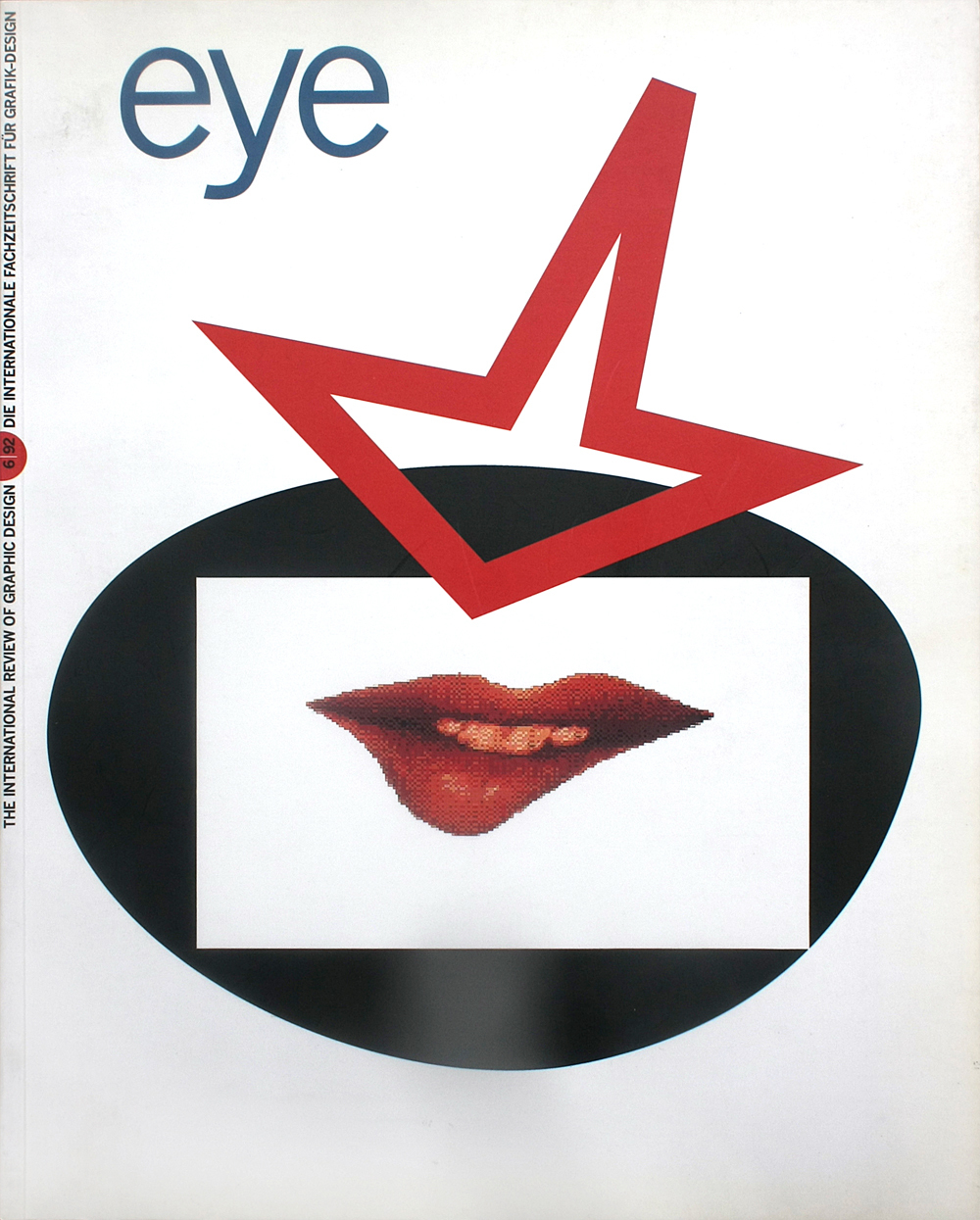

Strangely, it is Thirst’s joke-packed self promotional material which sometimes ends up being taken the most seriously. Four of the pieces selected for the 1991 100 Show catalogue were instigated by Valicenti simply to entertain. The Wrigley chair – ‘soft when warm’ – was made from 18,685 sticks of gum. Another was a Macintosh doodle that ended up as an April Fool’s Day card. ‘An ellipse here, a square there, some type – boom! It’s done,’ notes Valicenti in the catalogue. Why did he submit them? To be ‘totally twisted’ and show up the awards system.

Valicenti’s crusading spirit has been best put to work for his commercial clients. The in-house print designer of Cooper Lighting called in Thirst to jolt the company so radically that buyers were disappointed with the actual products. The product development division responded with a redesign.

Another example of what Valicenti calls ‘total collaboration’ is his relationship with Gilbert Paper. Valicenti suggested that since he was in effect being asked to endorse the products, he should be allowed to approve the entire range. Now he chooses colours, designs watermarks and specifies that all the stock be made from recycled material. The freewheeling collections of imagery that make up two promotional volumes show Thirst at their most experimental. The book The IZE Have It, designed in a style that might be described as pop mysticism, demonstrates how a recycled paper performs under complex printing specifications by stretching a repeated image of a face to the limits of recognition.

New technology fuels Valicenti’s work, so it is no surprise to find that he harbours televisual ambitions. Having contracted the video bug while making his short for the AIGA talk – lots of car windows, camera shake and electronic musak – Valicenti is keep to use the ‘Budweiser language’ of commercials to support causes dear to his heart, such as the AIDS crisis. ‘At this moment TV has no real use for anything that is activist in nature, but I think it’s there that I could be of some service, because my personal involvement is more genuine than that of marketers. There’s no nugget jewellery on my wrist. I think I can either raise consciousness or raise money.’ And here, in a neat duality – commerce with a conscience – lies the challenge of Valicenti’s approach.

First published in Eye no. 6 vol. 2, 1992

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.