Summer 2014

Open up the future

As São Paulo prepares for the 2014 AGI Open, Cláudio Ferlauto argues that design education in Brazil is endangered by new priorities

Brazil has nearly 800 design schools, and most of them offer courses in graphic design. The more traditional ones evolved from the architecture or fine arts schools, which included courses in product and graphic design (then known as ‘visual programming’) in their curriculums. The irony is that, despite this rich diversity, more than twenty design courses are now in the process of being discontinued.

Over the past few decades, Brazilian design education has become increasingly segmented. New courses, including fashion, digital design, branding, game design and typography have emerged, influenced both by the market and by the demands of new technologies. But here a paradox arises – the Ministry for Education and Culture has been introducing change to these schools by suggesting they offer only a basic design curriculum for undergraduates, leaving the more specific niches to be explored by postgraduate and specialised courses.

Brazil produced top-quality graphic design long before the introduction of computers. The first school of design was established in 1964 by an impressive generation of professionals from diverse backgrounds. The work of these early designers, all done by hand, became well known throughout the world through a special edition of Print magazine in 1987, guest edited by Felipe Taborda. In 1994, Brazil was the guest of honour at the Frankfurt Book Fair.

The high quality achieved by the postwar generation of designers, who were active both in teaching and professional practice over the period 1950-80, was the consequence of a serious commitment to design education in Brazil. The first initiative took place in São Paulo – Brazil’s largest industrial centre – with the introduction in 1962 of several design disciplines at the University of São Paulo. Not long after, in 1964, the School of Industrial Design – the first institution devoted exclusively to graphic and industrial design – was created in Rio de Janeiro, the country’s cultural centre.

The European connection

Both initiatives were related to earlier events. In 1950, the Bauhaus-trained Swiss designer and artist Max Bill – at this point engaged in founding the Ulm School of Design in Germany – had a retrospective at the São Paulo Museum of Modern Art; the following year he was awarded the grand prize for sculpture at the São Paulo Bienal. His, and Ulm’s, influence on Brazilian designers was seminal. Later in the 1950s other Brazilians, including Alexandre Wollner, studied at Ulm, and in 1959 Otl Aicher (with Bill, one of Ulm’s co-founders) and Tomás Maldonado (Bill’s successor as director) lectured at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro.

That period was marked by the activities of design pioneers such as Wollner and Aloísio Magalhães who, besides working in educational institutions, sought to educate the sector about the needs of designers. They created the first organisation for designers, the Brazilian Association of Industrial Design and they developed courses, workshops and other events in which many distinguished designers took part, including Fernando Lemos, Ruben Martins, Goebel Weyne and Karl Heinz Bergmiller, as well as Wollner and Magalhães. Design students also often had a good education in traditional disciplines, such as architecture.

But it wasn’t only the universities that contributed to educating students. Across the world many designers, such as Paul Rand in the United States, brought experience from related areas, such as advertising or art. And the same was true in Brazil, where notable examples included artists like Poty and Nelson Boeira Faedrich; more recently, they have been followed by Miran – Oswaldo Miranda – and Tide Hellmeister.

Nowadays, in addition to traditional foundations such as typography, colour, layout and grid, the borders of the design profession have been expanded by new elements, such as layers, transparencies, animation and randomisation. These have resulted from changing perceptions and transformations in both the social and technological worlds. In the late 1980s, the phenomenon of ‘re-foundation’ or ‘restart’ of graphic design had a wide influence on the profession, the market and design education. This tsunami of change is ongoing and new elements keep being incorporated – for example the combination of light, movement and sound resources presented by Kenya Hara at the AGI Congress launch conference in São Paulo in February 2014.

Since the 1980s, we have seen big changes in the career paths of Brazilian design professionals. Some designers, such as Rico Lins and Felipe Taborda, opted to study in the United States or Europe. They wanted a more challenging education that incorporated the spirit of globalisation promised by new media. At the same time, Brazilian universities have begun to educate researchers and historians through their masters and doctorate courses, despite the reduced education programme in undergraduate courses.

This model now has a decisive role to play in design education in Brazil, forcing the public universities to adapt to compete. In 2006 the University of São Paulo separated its design course from its courses in architecture and urbanism. Other public and private universities have followed the same path. One case is the Catholic University in southern Brazil, whose design course made it into Business Week’s list of the global top 30 design education institutions in March 2014.

The combination of a government policy of mass education for schoolchildren – demanded by the huge economic conglomerates that are investing in Brazil – and our own Ministry for Education and Culture’s programme of cutting down the number of courses at universities (and thereby cutting costs), has resulted in a new generation of designers with a weaker cultural background. Since the 1990s, with the big changes caused by the widespread use of the Web, young students are confronted daily with a huge flow of information, but lack the know-how to transform it into substantial knowledge.

This year’s AGI Open, which takes place in São Paulo on 18-19 August, is a great opportunity to demonstrate two highly contrasting realities facing this new generation of designers. First, they need to take the initiative themselves to prepare for their future by taking advantage of the possibilities offered by existing networks. Second, although cultural exchanges are valuable, studying abroad isn’t a simple decision, since Brazil’s challenges exist in other countries as well, often on a bigger and more complex scale. So improvements in Brazil’s design education system are essential for cultural and economic development.

The presence of an international group of designers at the AGI Open in São Paulo, as well as direct interactions through lectures, workshops and meetings, will be extremely important for both students and professionals. Through this event, Brazilian designers will be able to re-evaluate where they stand, intellectually, personally and professionally, and compare themselves to their peers from other parts of the graphic design world.

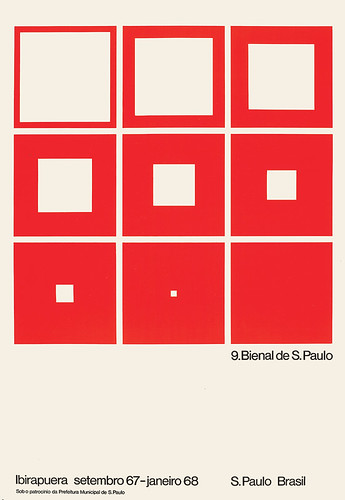

Goebel Weyne, poster for the ninth biennial, 1967.

Top: Miriam Zlochevsky Tunchel, Shadow Piece Y. O. Posters inspired by texts and poems by Yoko Ono, designed by students studying for the masters degree in graphic design at FAAP, Fundação Armando Alvares Penteado, São Paulo Brazil.

Cláudio Ferlauto, designer, writer, editor, São Paulo

First published in Eye no. 88 vol. 22 2014

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. You can see what Eye 88 looks like at Eye before you buy on Vimeo.