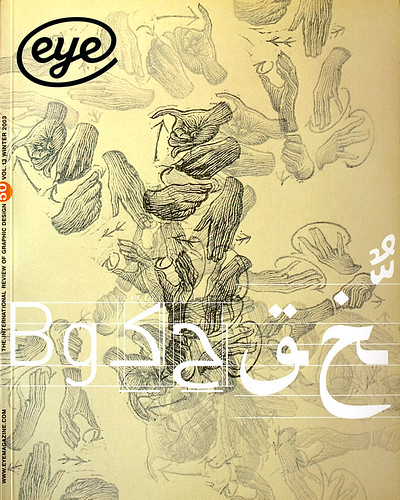

Winter 2003

Pre-postmodernity

Saul Bass

Max Bill

Derek Birdsall

Chermayeff and Geismar

Anthony Froshaug

Robert Massin

Josef Müller-Brockmann

Jan Tschichold

Henry Wolf

Bob Cobbing

Does a small book from nearly 30 years ago encapsulate a ‘golden age’?

I have a theory: the period from the late-1960s to the mid-1970s is the most important, artistically speaking, of the post-war era. My theory is based on the aesthetic prejudice that the years between the end of 1960s utopianism and the beginning of the electronic ‘age-of-information’, look increasingly like a golden age for art, design, film, literature, pop and jazz. This was the era that produced Richard Hamilton’s cover for The Beatles, the ‘white album’ (1968), Bitches Brew by Miles Davis (1969) and Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976). It was a time when the experimental entered the mainstream.

My prejudice in this matter is strengthened by the belated discovery of a small, modestly designed and written book called Art without Boundaries: 1950-70. I say ‘belated discovery’, because I first made a note to track it down after Rick Poynor adapted the title for his 1998 collection of essays Design without Boundaries. The original book appeared in 1972. Though it features work from the 1950s and early 1960s, its tone and message is quintessentially of its time. The book is edited by Gerald Woods, Philip Thompson (who also designed it) and John Williams. As Woods explains in his preface, he started out on his own but quickly saw the benefits of collaboration. No biographical information is given for the editors, although Woods mentions that he was ‘teaching at two London art colleges’ when he conceived the book in 1968; there is also a tiny picture of him looking like a member of the Dave Clark 5.

The jacket-blurb announces the book’s central theme: ‘The most exciting, and possibly the most fruitful, trend in the visual arts since the early 1950s has been the steady erosion of traditional boundaries: between painting and sculpture, painting and film, film and typography, photography and print-making, “fine” and “commercial” art.’ In the book’s short introduction the theme is expanded upon: ‘At one time it was easy to distinguish between the “fine” artist and the “commercial” artist,’ the editors note. ‘It is now less easy. The qualities which differentiated the one from the other are now often common to both. The painter, who once saw the commercial designer as a toady to the financial pressures of industry, may now find that the dealer can impose a tyranny worse than that of any client. During the last twenty years or so, barriers have been broken down: and they are still being broken down.’ The editors’ well argued enthusiasm for the erosion and dissolving of traditional lines of artistic demarcation makes this book a resonant record of ‘the golden age’.

To make their case, the editors provide examples of work from 70 artists. Short biographical sketches accompany each entry, often using the artist’s own words. It is a roll-call of the great, the legendary and the stellar:

Saul Bass, Max Bill, Derek Birdsall, Mark Boyle, Bill Brandt, Chermayeff & Geismar, Christo, Bob Cobbing, Federico Fellini, Anthony Froshaug, Jean-Luc Godard, William Klein, Sol LeWitt, Robert Massin, Josef Müller-Brockmann, Claes Oldenburg, Alain Robbe-Grillet, Jan Tschichold, Stan VanDerBeek and Henry Wolf. The temptation to list all 70 is strong … but let’s just say that there are no duffers, and when mixed together they make an alchemical brew of intoxicating delight.

The work catalogued in Art without Boundaries has an unmistakeable sense of underlying cohesiveness; there is no jolt or rupture as you move between say, Godard and Froshaug, Cobbing and Robbe-Grillet. But this aesthetic commonality should not be mistaken for mere period uniformity; what you get are examples of work executed within a shared and rapidly democratising cultural landscape; a flat landscape that allowed artists, designers and film-makers to move freely between disciplines. This cultural levelling was the consequence of 1960s anti-authoritarianism and the liberalisation of institutions and media; artists were quick to take advantage of this new freedom.

The book shows the flowering of a new inter-disciplinary fluidity; what the editors describe as a new ‘interaction of media’. As they note: ‘Warhol and Rauschenburg began to silkscreen photographic half-tones directly on to canvas … Godard interspliced verbal messages with film sequences. Antonioni “painted” with film. Genoves produced paintings in series that emulated the sequences of images which one sees in newsreel films.’ The book’s authors believed that art had entered a new era of creativity. The ‘white heat’ of the 1960s techno-logical revolution had opened up new vistas of possibility. The old labelling systems beloved of authoritarian hierarchies were about to become redundant: the barriers were down.

But their optimism has not been vindicated by the passage of time. The situation today has reverted to pre-1960s rigidity; the barriers are back and they are stronger than ever. Regardless of the lip-service paid to postmodern intertextuality, artists today cross boundaries at their peril: art is art; design is design; film is film. To use a phrase much loved by marketing people, we live in a niche world: a world where competition is so intense, commercial necessities so ferocious, that for artists to survive, they must offer the world no blurry indeterminacy. It is commercial suicide for the artist, the designer, the musician, the film-maker, to offer their audiences anything that cannot be labelled as clearly as a road sign.

Today’s barriers are not cultural or societal, as they were in the 1960s; we are hemmed in by barriers erected for commercial reasons. Galleries and curators want to maintain the elitism of fine art and stress its separateness from the commercial field; graphics is about branding and business problem-solving; film is either ‘video art’ or it is Hollywood; musicians must slot into a rigid labelling system or risk not finding outlets for their music. Of course, artists can – and many do – ignore this new cultural territoriality, but those that do are frequently condemned to penury and outsiderdom.

Could a version of Art without Boundaries be produced today? Yes, but not without cocking a snook at snobbery and the suffocating power of commercial interests in cultural production. Perhaps if a contemporary version was to appear, it would herald a new golden age?

Adrian Shaughnessy, writer, creative director, author of Sampler nos. 1 - 3, London

First published in Eye no. 50 vol. 13 2003

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue.