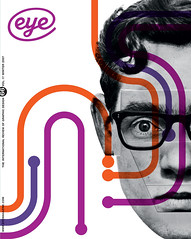

Winter 2007

Predictive text

A short history of the future can only start with a look at yesterday’s latest thing

Where do you start with the future? I guess the recent past is as good as anywhere: nothing is quite so dated as yesterday’s latest thing.

‘We’ve all smiled at predictions from the past that look silly today,’ Bill Gates reminded us twelve years ago in The Road Ahead, ‘such as the family helicopter and nuclear power “too cheap to meter”. History is full of now ironic examples – the Oxford professor who in 1878 dismissed the electric light as a gimmick; the commissioner of US patents who in 1899 asked that his office be abolished because “everything that can be invented has been invented”.’

When I started (long before the age of Gates) I typed out scripts on a manual typewriter, and made carbon copies for my files. If I had a question about the text I’d phone the client or write. The script would be posted and a week or so later would return with amendments. I’d retype the whole thing with changes. After a while I acquired a green-screen Amstrad word processor (with no hard drive) and a fax machine, and the whole editing and writing process speeded up.

Designers with equally long memories have parallel tales of Letraset, tracing paper and overlays. Today’s technology doesn’t necessarily help us write or design any better, but it certainly makes things faster, and affords clients easy access into many of the processes involved (and, by extension, the occasional urge to tinker). You cannot expect to democratise technology and not have ‘ordinary’ people getting involved – and (occasionally) becoming expert at it.

These days I’m no longer impressed by the fact that I could easily email the entire hard drive of my last-but-two computer; that my telephone is probably the best camera I’ve ever owned; that a record collection I needed a car to shift now resides in a thing the size of ten Woodbines. More worrying is the invisible trail you leave online throughout the working day – and the entirely visible piles of recently outmoded technology we scatter in our wake. John Maeda, associate director of research at MIT’s Media Lab, summed it up perfectly for me: ‘Change is inevitable in the context of progress. The garbage we leave for our future generations is a reminder that we were right to progress forward, and wrong as well.’

Carsten Beck, of the Copenhagen Institute for Futures Studies, believes this will change, but not necessarily because we finally address our enormous waste of finite resources: ‘Individualisation will be the strongest driver in relation to it. In the past we had “tech wizards” presenting us with the latest gadget or feature. In the future it will be the other way round: I will present some individual needs that technology might help me solve. And if the standard solutions are not good enough, I will search my networks to find people with similar problems / interests. People will want to be co-creators of solutions.’

Power to the people

Technology going democratic is a stirring thought: a mirror image of the people power generated by the internet itself. It’s probably no bad thing for Penguin to sell books with blank covers for the reader to design their own version: if nothing else, we gain some insight into just how challenging that process can be. The next question, inevitably, is whether we need physical books at all: HarperCollins is offering excerpts from its list for reading on your iPhone; e-paper offers a high-contrast, flexible medium that is legible even in bright sunlight; and Google is quietly scanning the edited highlights of culture, history, science – stuff – and rendering it virtual . . . and Google’s.

But as Daljit Singh, joint creative director of Digit London, reminds us, ‘Books are still the ultimate portable information device. It’s difficult to improve on a paperback you can pick up, read and throw away and not worry about: that’s still preferable to a £300 piece of technology just to read a book. Books, anyway, are my ornaments, a reflection of me and what I’m interested in.’ Design remains a hugely important part of the whole ‘book’ experience; though precisely the same was said about music of the vinyl era.

Mike Bennett, co-creative director at Digit, says that ‘people will hate Google in ten years, just because of that technology that follows you from site to site, and, based on that, the advertising that’s delivered to you.’ But he’s not about to give up: ‘It’s down to us as designers to work out how to design this stuff so it’s better for humanity rather than just for technology’s sake.’

Technology works best when it interacts with people and the way they act and behave, rather than simply bypassing them: that’s the great advantage of Nintendo Wii: it replicates basic human actions and thus brings the notion of what a ‘game’ is back to what a game once was: a physical interaction in the real world.

Nokia’s design focus is evolving from an essentially pioneering outlook to a dynamic one. Only in fine art these days is there the luxury of total independence from the consumer. ‘With the volumes we work at,’ says Matt Bickley, senior creative at Nokia Design Communications, ‘in a rapidly saturating market, you simply cannot afford to be gung-ho. Nevertheless, now is easily the most exciting time to be involved; we’re entering into a realm no longer just about products and capabilities, but more about changing definitions. We’ve moved from “mobile phones”, text and cameras, to multiple experiences on the go. We’re helping empower a more democratic world, with everyone from a City banker to a fisherman in India essentially having a voice and access.’

Material girls and boys

Physically moving around stuff is still really important to people: doing this exclusively with a mouse and a finger is not the same. You buy a sofa by sitting on it in a place; the best you can do online is narrow down your search. Physical interaction is never going out of style. And that’s where the future should be; in the meshing of the virtual and real.

So, it might be argued, technology is best when it is invisible, like some special effects in movies. ‘Microsoft is now working on Minority Report technology – where Tom Cruise literally grabbed information out of the air,’ says Bennett. ‘It looked fabulous, and very natural, and

that’s now being replicated.’ (See Eye no. 60 vol. 15.)

‘Technology will be less important physically,’ Beck adds. ‘Some nicely designed gadgets might still be present but otherwise the interfaces between people and machines will disappear. What will the average Joe brag about ten years from now? Today it is material: in the future it could be immaterial: peace and quiet; just being Off.’ Maeda takes that argument a stage further: ‘We don’t need anything except people in the end. Nothing more.’

It has always been – and always will be – about great ideas. But Hani Rashid, architect at the New York-based Asymptote, offers cautionary advice: ‘Great ideas are just that, unless fully and passionately engaged by those that have the real control, and educating these power brokers is a full time job and more. Particularly today, with intense and increasingly complex mixed agendas swirling about, such as new-found (and necessary) environmental concerns, ever fluctuating economies and gyrating markets, dramatic swings in goods, prices, materials and above all the highly dubious and precarious terrain of public taste and its easily malleable state. I find history, intelligence, logic and even common sense take a back seat to hard-core figures, striking images and marketing ploys. And these are precisely the weapons that we need to hone, to manifest truly inspired and pertinent ideas and works.’

Signs of the times

Such a brief and general survey can do no more than scratch the surface of a subject that is – quite literally – infinite. There are no boundaries to the future, and the only way to appreciate this is retrospectively. Once upon a time you watched a movie and dated it by, well, the fashions, the cast, the cars. As change has accelerated, that mental process has become so much more precise. You can date a film almost to the month by the size of mobile phone its protagonists use.

‘We will date films in the future by the quantity of real things in them: objects, images, actors,’ suggests Maeda. Futurologist Sean Pillot de Chenecey, of Captain Crikey, was probably closer to the mark: ‘One of the more worrying angles here simply relates to population dynamics. There’ll

be a lot more old people as a percentage of the population in the future, which is going to have profound implications.’

Movies of the future will be full of old guys, talking about carbon copies and Letraset.

Steve Hare, freelance journalist, author, Wiltshire, UK

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.