Spring 2013

Puffins on the plate

How the Russian revolution – plus new technology – led to a colourful and radical change in children’s book publishing.

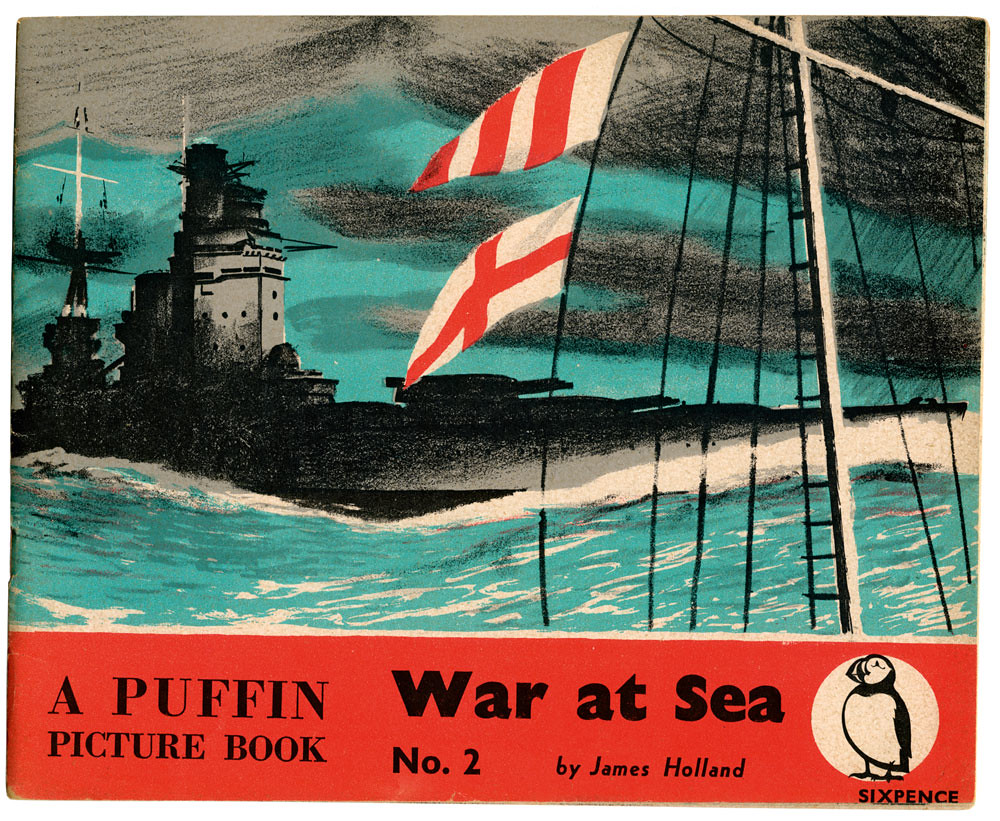

We remember the 1936 launch of Penguin Books, quite rightly, as a historic moment in publishing. But there is another memorable achievement by Allen Lane’s company that is equally deserving of celebration: the first Puffins. Designed for children and first issued in 1940, Puffin Picture Books were filled with colourful illustrations, yet cost only sixpence, no more than an ordinary paperback.

How could a wartime publisher offer children such cheap, beautiful books, without government subsidy – and at a profit? The short answer is that the books were designed and illustrated by artists working directly on lithographic plates and thereby cutting production costs; that they could do this is thanks to a revolution in the design and illustration of children’s books that began in Soviet Russia.

Lenin saw the education of a largely illiterate population as a top priority, and as early as 1918 announced through the state newspaper Pravda: ‘The children’s book as a major weapon for education must require the widest possible distribution.’

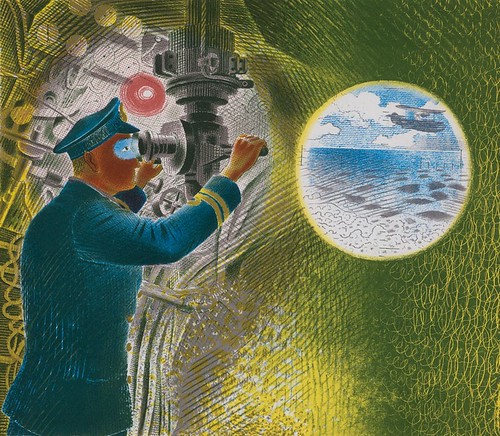

Submarine Commander Looking Through a Periscope by Eric Ravilious, 1941. One of ten wartime lithographs, known collectively as the Submarine Series, which were drawn by Ravilious and printed by Geoffrey Smith at W. S. Cowell, Ipswich.

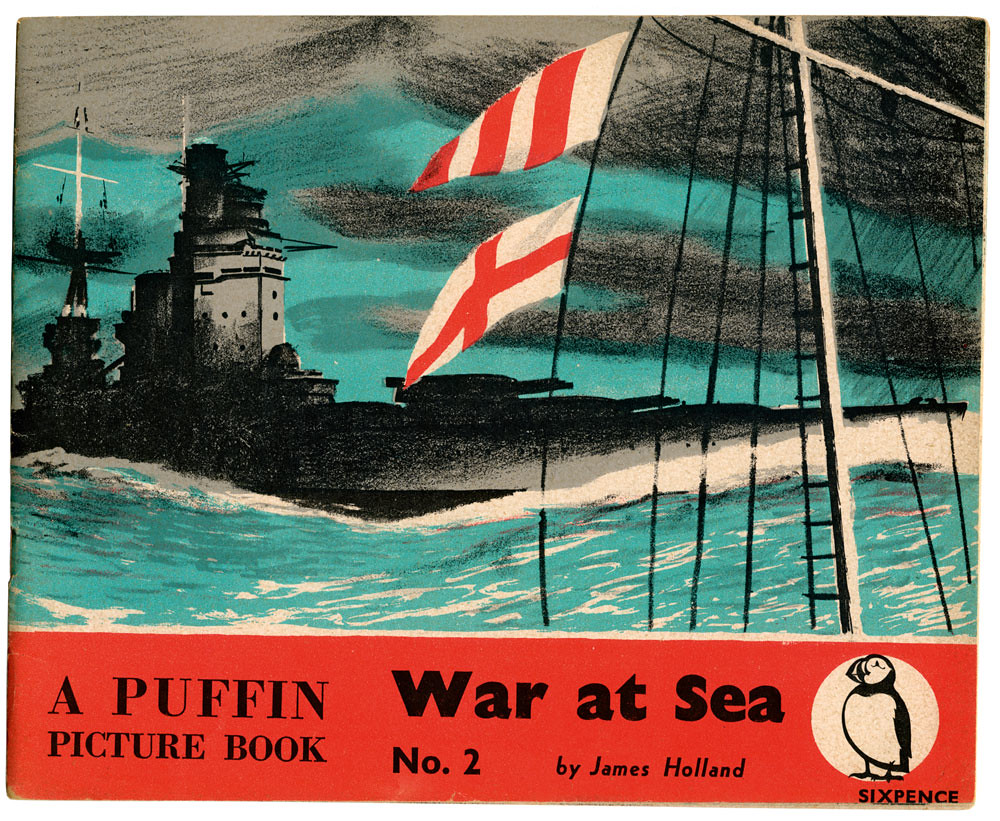

Top: cover of the second Penguin Picture Book, War at Sea, by James Holland.

His aim was to teach children about the world they lived in and about the technologies that would transform Russia into a Modernist utopia, and the approach adopted by the state publishing houses Raduga (Rainbow) and then Detgiz, or ‘Giz’, was highly innovative. The books were printed in huge numbers and widely distributed; cheaply produced on flimsy paper, yet blazing with colour and energy, they were designed for children to enjoy rather than treasure. Artists deprived of a conventional market for their work by war and social upheaval channelled their creative energies into the project, using offset lithography to produce an immense variety of work.

At the forefront of this revolution was Vladimir Lebedev, artistic director at the Petrograd branch of Giz and creator of a breathtaking range of illustrations depicting farm and countryside, trains and boats, dams and factories. ‘Art must be the same nut for a child as it is for an adult,’ he once commented, ‘only the nut intended for the child ought not to have too hard a shell.’

Between 1918 and 1931 almost 10,000 children’s titles were released in the USSR, while the same period saw this publishing revolution carried beyond Russia by those artists, writers and intellectuals who rejected the Communist regime. Initially, the exiles gathered in Germany. But by the mid-1920s, Paris had replaced troubled Berlin as the centre for Russian émigré life.

As the European cultural capital, Paris was also a cauldron of new ideas, among them the concept of child-centred education, one of whose Parisian champions was the bookseller Paul Faucher. He saw that the aims of the movement, rooted as they were in respect for the rights and autonomy of the child, required a new approach to children’s books similar to that pioneered in Russia.

Faucher found in Russian émigré Nathalie Parain (née Tchelpanova) the ideal artist for his new Père Castor series of picture books, and in 1931 the first title was issued by publisher Flammarion. Je Fais Mes Masques featured eight life-sized masks from different cultures, each lithographed in bold colour and designed to be cut out; this book mattered less as a material object than it did as a source of inspiration for the child. The approach proved popular and, as more titles followed, Russian émigré artists were in demand.

Cover of Pochta (Post), illustrated by Mikhail Tsekhanovsky, with verses by Samuil Marshak and published by the Soviet state publishing house Detgiz, USSR, 1928.

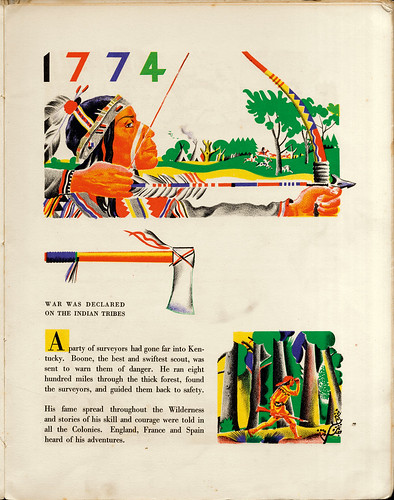

Chief among them was the flamboyant Feodor Rojankovsky (1891-1970), who had risked his life opposing the revolution as a soldier in the White Army. Having escaped to Poland and then to Paris, he was commissioned to illustrate Daniel Boone, a suitably adventurous children’s book about the eponymous American frontiersman. Released in 1931, the book was a sensation, with Rojankovsky working directly on the stone at the Atelier Mourlot (where Picasso and Matisse later worked) to create lithographs of a vibrancy not seen before in French picture books.

It took longer for the influence of Russian illustration to be felt in Britain. In 1933 the artist Pearl Binder (1904-90) returned from a visit to the Soviet Union with a pile of mass-produced children’s books, which she took to the publisher Noel Carrington. As the father of a child who suffered polio and had therefore to be taught at home, Carrington was stunned by these books; his reaction was immediate and deeply felt: ‘Why couldn’t we produce these here?’

The first challenge was to find artists who could design and print their own illustrations using autolithography. This was, Carrington felt, the key ingredient, both because artists working directly on the stone could achieve an unparalleled boldness and directness, and because of the cost saving. Unusually, the most creative approach was also the cheapest, but where were these artists to come from?

Barnett Freedman had been learning autolithography with master printer Thomas E. Griffits for some time and was already producing colourful advertising materials and book jackets, but Harold Curwen, owner of the Curwen Press (see Eye 70), was nevertheless lamenting ‘the lack of direct work by the artist’ in commercial lithography.

However a small but expanding group, centred around London’s Central School of Art and Crafts, was challenging this status quo, driven by a belief that autolithography could serve a progressive political agenda.

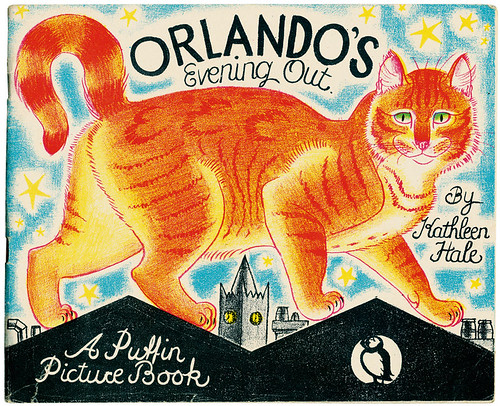

Cover of Orlando’s Evening Out by Kathleen Hale, 1942. Two titles in the popular Orlando series were published as Puffins, the other being Orlando’s Home Life.

On her return from Moscow, Binder co-founded the Artists’ International (later the Artists’ International Association AIA), which sought to spread the pleasures and benefits of art more widely among the British public; she and a number of her co-founders, committed young artists such as James Holland (1905-60), were students or practitioners of autolithography.

Eric Ravilious (1903-42) was another AIA member who adopted the medium, creating in 1936 a radiant picture of a steamship heading into port, which was known officially as Newhaven Harbour and by the artist as his ‘homage to Seurat’. A talented watercolourist and wood engraver, Ravilious became fascinated by autolithography, which he used to illustrate High Street (1938), a book of shops published by Carrington for Country Life Books as a children’s title. Ravilious’s love of the idiosyncratic found perfect expression in the 24 shop fronts and interiors, and reviewers praised illustrations that had ‘wit and elegance, as well as gaiety, in every line.’

Carrington, meanwhile, had found a valuable ally in Geoffrey Smith, of the printers W. S. Cowell (see ‘Pictures on a page’, Eye 84). Like Curwen, Cowells had enjoyed success printing music in the nineteenth century but in 1934 Smith took the business in a radical new direction by printing an English translation of Jean de Brunhoff’s children’s classic The Story of Babar the Little Elephant.

His appetite for colour lithography whetted, Smith went on to work with Edward Ardizzone (see ‘Told in pictures’) and then Kathleen Hale (1898-2000), whose book Orlando the Marmalade Cat was published by Carrington.

‘Geoffrey Smith kindly arranged for me to learn the rudiments of lithography by doing the works at Cowells,’ Hale later reported, ‘with advice and help from the firm’s lithographic department. These men could have been resentful of a complete amateur, for they had all been through a seven-year apprenticeship, but they were all marvellously helpful and friendly.’

The willingness of Smith and his men to work alongside artists, coupled with the adventurous spirit of the artists themselves, enabled Carrington in 1938 to approach Allen Lane with a proposal for a series of affordable illustrated paperbacks. Lane jumped at the idea, and once his mind was made up not even the outbreak of war could deter the production of the first Puffin Picture Books, which were drawn directly on the plate by artists, including AIA pioneer James Holland.

‘The worst has happened,’ Lane told Carrington, ‘but evacuated children are going to need books more than ever. Let us get out half a dozen as soon as we can.’ Children’s publishing would never be quite the same again.

Emigré artist Feodor Rojankovsky was commissioned to illustrate Daniel Boone by Esther Averill, published by Domino Press (Paris), 1931.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue. You can see what Eye 85 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.